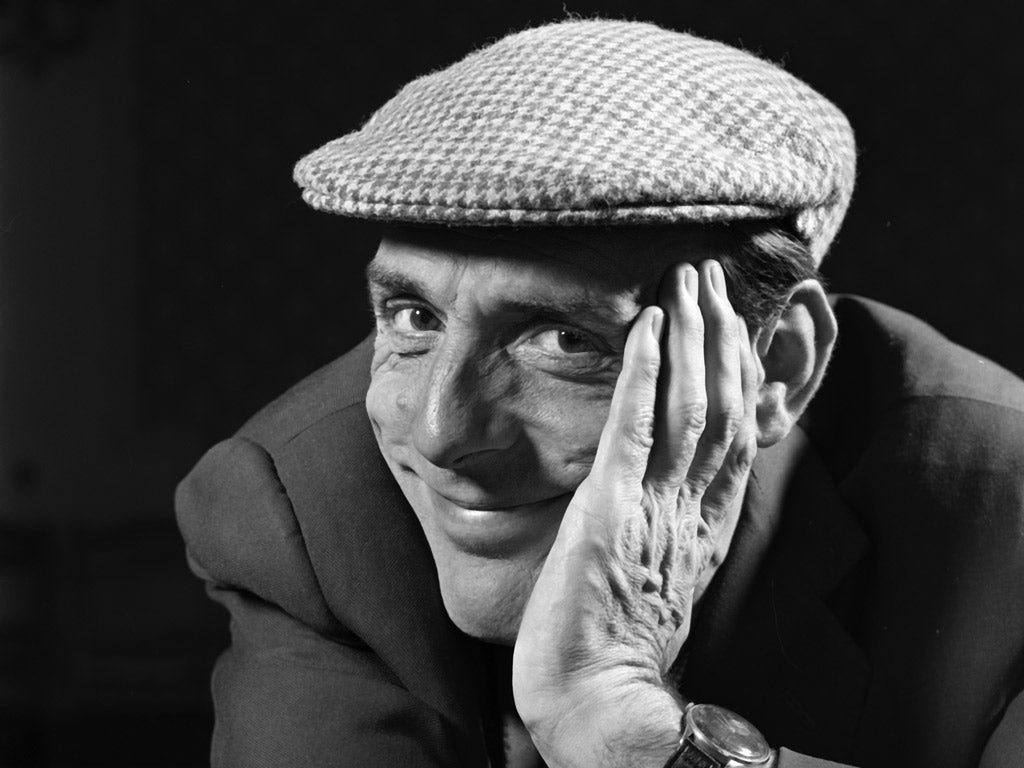

Eric Sykes: Actor and writer who overcame adversity to become a leading figure of British comedy

He wrote Goon Shows with Spike Milligan but had to stop: 'We fought about everything'

Eric Sykes overcame an emotionally deprived childhood and an adulthood of disability to become one of Britain's leading comedy writers and performers. Sykes was born in Oldham in 1923. His mother Harriet, died in childbirth, aged 22. This was to be a defining event in Sykes' life, not least because his father, a cotton mill overseer, went on to marry again and had another son upon whom the couple doted. To compound matters, Sykes' elder brother was doted on by the relatives of his late mother. Sykes would later describe his experience of growing up as "being a lodger in my own home" and compared himself to an orphan.

He would grasp any connection with his mother. A Swansea fortune teller whom he once consulted later in life told him that his comedic talents represented his mother speaking through him. Sykes wholeheartedly agreed with this. Many friends wondered if even his choice of long-term comedy partner, Hattie Jacques, might have been influenced by her sharing his late mother's name. Sykes would refer to her with the same nickname as his mother's – Hat.

Sykes even ascribed healing powers to his mother. After an operation for his hearing in 1962 left him deaf, he prayed to her. Four days later, he found he could hear the noise of rain on the window. The medical conclusion was that, as Sykes had no eardrums, there was no reason why some of his hearing should have returned. For Sykes the explanation was simpler: "I know it was my mother's miracle. She must have heard me."

Despite being partially deaf and registered blind for most of his life, Sykes never let these disabilities hamper his career, prompting Spike Milligan to nominate him as "the bravest man I know". Sykes worked within the limitations of his physical restraints. He used a desktop device to magnify everything he read and had scripts recorded on to tape so he could learn them. He also wore electronic spectacles, the arms of which contained a device to conduct sound vibrations to the bone behind his ears.

The glasses allowed him to continue working and socialising, at least to some extent. Sykes admitted that he taught himself to laugh at jokes when other people were laughing, but would add that sometimes he only wished his spectacles could tell him where noises were coming from. Sometimes, he confessed, he would start laughing only to look up and, even with his severely restricted vision, see serious faces. Only then would he realise that the joke had been told three tables away.

The death of his mother may well have furnished him from the outset with the kind of melancholy life he believed to be necessary for a comedian – "The best comics have all got sad voices and lines of suffering" he once said – but it was the Second World War that provided him with the time and opportunity to create comedy. Indeed, Sykes held that the only way another crop of writers as talented as Spike Milligan, Denis Norden and Frank Muir could emerge again would be through conscription, providing as it did bed, board and the time to hone comedic skills.

As a young man, Sykes worked as a painter, a greengrocer's lad and alongside his father at the mill, at the same time as writing comedy, with plans ultimately to be a performer. He signed up for the RAF as a wireless operator, but had a curious service career during which he was attached to both the Army and the Navy. It was during the war, while he was in the odd position of being a sergeant with the Army, but not strictly in it, that he developed a comedy act for a concert party, using a gag book he had bought by post through The Stage.

Sykes saw active service too, when he landed in France on D-Day. "I'd lie in a slit trench on the beach, underneath a bit of corrugated tin that I'd found," he said. "The days were beautiful but the nights were horrendous."

After the war, Sykes went to London to try to make the grade as a scriptwriter, but his showbusiness career got off to such a shaky start that he was soon suffering from malnutrition. Bill Fraser, an impresario and comic whom he had met in the war, bumped into Sykes at this time and saw what a bad way he was in. Fraser asked Sykes to go and buy him some sandwiches from a shop and then tactfully engineered it so that Sykes ate them all himself. With Fraser's help, Sykes' career was subsequently launched just at the moment that the advent of television and the heyday of radio combined to provide a bonanza for scriptwriters.

The comedian Frankie Howerd, who had been in another wartime entertainment group and heard about Sykes, wrote to him to ask if could he use some of his army material. Sykes agreed and also started writing further material for Howerd, joining him in 1949 as a full-time writer on £10 a week. "It took me about five minutes to write Frankie's whole act," Sykes later said. "It was nothing to me to write it. I could write on the top of a bus or sitting in my dressing-room waiting to go on."

Despite Sykes' success as a writer, his main ambition was still to be a comedian. He persuaded Howerd to record an act with him, which was, as Sykes recalled, "Terrible. Frank said, 'Now do you believe me? Right, forget the stage; just be a writer.'" Sykes then collaborated for a while with Spike Milligan, writing three Goon Shows with him. Sykes stopped working with Milligan, however, because "we fought about everything".

The two continued to share an office above a greengrocers in Shepherd's Bush, however, later moving to a mews house in Bayswater. This served for many years as a kind of "Comedy Central", presided over by Sykes, who was at one point the highest paid comedy writer in Britain, simultaneously working on a series for Tony Hancock and the radio show Educating Archie and also doing material for Bill Kerr, Alfred Marks, Harry Secombe and Peter Sellers.

After seeing Hattie Jacques singing "My Old Man Said Follow The Van" at The Players' Theatre, Sykes decided he had found the key to launching his performing career. "She was singing – and holding a parrot in a cage," Sykes said of the notably rotund comedienne. "At the end of the number she leapt in the air and did the splits. I had never seen such charisma."

Sykes was soon starring with Jacques in a TV sitcom, Sykes and A..., that he wrote and in which they played a brother and sister living together in a terraced house. It was launched in 1960 and the series continued, as plain Sykes, into the late 1970s.

Sykes stopped submitting scripts to the BBC in the 1980s when he was informed that he was too old. But this did not stop this self-acknowledged workaholic from developing new projects and writing from nine to five in the Bayswater office. He wrote four novels, The Great Crime of Grapplewick (1984), Eric Sykes of Sebastopol Terrace (1981), UFOs are Coming Wednesday (1995) and Smelling of Roses (1997), as well as continuing to develop his performing career. In 1997, he played the servant Alain in Peter Hall's stage production of Moliere's School For Wives and later played a manservant in a BBC2 adaptation of the Mervyn Peake novel Gormenghast.

He also appeared regularly in panto, and was in a West End stage comedy, Ray Cooney's Caught in the Net, as late as 2001, when he was 78. Sykes also had parts in more than 20 films, including Those Magnificent Men In Their Flying Machines (1964), The Liquidator (1965) and The Plank (1980), a silent film farce in which he starred alongside Tommy Cooper.

When he was 76, Sykes was offered the role of Nicole Kidman's gardener in a film thriller, The Others, by the director Alejandro Amenabar. Of this part, on which he spent nearly a year in Spain, he said: "It's a wonderful experience for me at my time of life. It's like turning up to a party to discover all the food has gone, then learning they have saved a large piece of cake for you." He also appeared in the Harry Potter franchise, playing a caretaker in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2005).

As might well befit his often unfortunate life, Eric Sykes' comedy was distinctive for its melancholic, sardonic edge. An early gag for Frankie Howerd typified the genre. It was about an old lady taken to the seaside for the first time in her life. After gazing at the sea for a while, she says, "Is that all it does?" As a performer, he had a flat, Lancashire voice that was capable of great sarcasm, but that he regarded in his down moments – which were many and profound – as plain dull.

Politically, Sykes came from the right. In the 1970s he and his friend Jimmy Edwards took part in a morale-boosting show for Ian Smith in Rhodesia, and a journalist interviewing him in 1999 noted on a shelf a copy of Ayn Rand's cult libertarian novel The Fountainhead.

Sykes married Edith Milbrandt, a Canadian nurse whom he met in 1952 when she looked after him after one of his ear operations. As well as being dogged by his well-known disabilities, in 1997 Sykes had a quadruple bypass after a promotional tour for one of his novels. Typically he dealt with it with humour: "I don't know if it was a triple or a quadruple bypass," he told the press. "I wasn't counting at the time."

This response was in line with his belief that good comedy was medicinal. He maintained that one of Ken Dodd's shows was the equivalent of six months on the National Health. Sykes once commented that death "won't be so bad as it will mean the time has come when my mother and I might meet face to face. I do hope we do, as I would so like to thank her for all she has done for me."

Eric Sykes, actor, scriptwriter, director and producer: born Oldham, Lancashire 4 May 1923; OBE 1986, CBE 2005; married 1952 Edith Milbrandt (one son, three daughters); died 4 July 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks