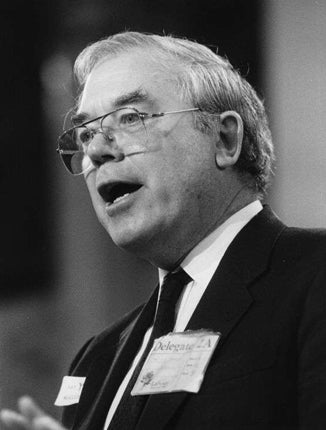

Eric Hammond: Electricians' leader who helped Rupert Murdoch smash the unions and move to Wapping

Eric Hammond, the former general secretary of the Electrical, Electronic, Telecommunication and Plumbing Trade Union (EETPU), who has died aged 79, was the trade-union movement's most enigmatic maverick and was generally credited with helping Rupert Murdoch establish his Wapping empire and break the print unions. He was the man the Left most loved to hate, yet even his avowed enemies had grudging respect for him.

He was arguably Britain's most influential and rebellious post-war union leader. Although he was a committed Labour Party supporter, Hammond detested those he deemed to be in the camp of the "lunatic Left". He was a staunch anti-communist and was not prepared to allow his union or his office to be used for political purposes. Hammond simply believed that he was there to serve the best interests of his members and always tried to put them first, whatever the consequences to himself or his image.

Unlike his enemies on the Left, Hammond preferred to let his members decide their future through the ballot box rather than be manipulated by the unrepresentative committees he deeply loathed. His predecessor Frank, later Lord, Chapple, was also a high-profile right-winger (after severing links with the Communist Party) and when he took over from Chapple in 1982 his colleagues told the media: "If you think Frank is right-wing just wait until you see Eric." They did not have long to wait.

The second of three children, Eric Albert Barratt Hammond was born in York Road, Northfleet, Kent, in 1929. His father was a labourer and soldier in the trenches of the First World War. Eric Hammond worked his way up the trade-union ladder to give his membership what he passionately believed in – democracy, fairness and realism. Certainly, his members appeared always to be in tune with his thinking.

He enjoyed a typically English working-class 1930s childhood but spent his wartime teens in Newfoundland as an evacuee where he adopted much of the local culture and played ice hockey. Returning to England in 1945 he became an apprentice electrician and member of what was then the Electrical Trades Union. At 17 he was an officer and active member of the Labour Party. Union talent-spotters quickly ensured that he became a shop steward and convener on key power-station and refinery sites.

He was elected to the union's national executive in 1964 and became General Secretary 18 years later (EETPU was formed in 1968 from an amalgamation of electricians and plumbers). On re-election in 1987 he received the highest vote ever accorded a trade-union leader or candidate to public office in Britain.

His hatred of the extreme Left was matched almost by his contempt for weak leadership of so-called moderates and the ineffectual Right. In his autobiography Maverick (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1992) he talks of the bitterness and behind-the-scenes deals which led to a revolution in the way the Trades Union Congress did business. He did not endear himself to senior TUC General Council members and did not go out of his way to make friends with them. At various times he described them as "clowns", "a bunch of fools" and "knuckleheads". In his book he also described graphically how his lead was followed by the Left in accepting Government cash for secret ballots and signing no-strike deals, the "crime" for which his union was expelled from the TUC in 1988. He also pulled no punches in his fascinating account of how he helped Murdoch smash the print unions, an act for which he will never be forgiven by his brothers and sisters in what used to be called Fleet Street.

He later fell out with Murdoch, an event which most of his critics thought inevitable in the circumstances. It is extremely doubtful that Hammond rubbed shoulders with Murdoch purely because he wanted to hobnob with management. It is more feasible that he wanted to further his members' careers and developments in new technology at Wapping and elsewhere, and saw the print unions merely as union dinosaurs while the EETPU moved into the future as an innovative union trained for the 21st century. The fact that the print unions had balloted democratically to oppose Murdoch did not appear to bother him. The settling of old scores was icing on the cake.

After the Wapping dispute in 1986 he was regularly flanked by bodyguards, an unusual position for a British trade-union leader. Hammond appeared positively to relish baiting left-wingers and always adopted a belligerent attitude when confronting activists. He was quite happy to describe unnamed SOGAT officials as "thugs". At the TUC in 1983 he denounced "terrorists, lesbians and other queer people in the GLC Labour Party", and during the miners' strike the following year described members of the National Union of Mineworkers as "lions led by donkeys". He did not hide his loathing and contempt for NUM leader Arthur Scargill. But, like Scargill, he knew how to use power when he had it. Even in childhood he realised that security came from "teaming up with the smartest and the strongest – collective action".

In 1983 he also made an audacious attempt to join the employers' Confederation of British Industry and argued that, as an employer who provided training, he was entitled to membership. He was turned down, but was later welcomed as guest speaker at a CBI conference. He also invited Norman Tebbit, then Trade and Industry Secretary, and the Left's bête noire because of his anti-union laws, to open the union's new high-technology training centre at Cudham, Kent.

Observers could clearly be forgiven, in the circumstances, for wondering whether the "minders" were to protect him from some of his own members, particularly those of the diehard Left in the troublesome London Press Branch of the EETPU, a group, including Communists, whose spiritual heart was with the print unions.

He did not care that the Fleet Street print unions had behaved democratically by striking against News International after a secret ballot in 1986. He and his union had collaborated with Murdoch in setting up the Wapping operation, a success which could not have been achieved without the willingness of the EETPU to recruit alternative labour. He remained impervious to criticism and faced the flak bravely and stoically. During the ensuing bitter battles, the TUC surprisingly chose Hammond as a peacemaker with Murdoch. Their reasoning, no doubt, was that because Hammond had got them into the mess Hammond might as well get them out of it.

Hammond's secret talks with Murdoch and the Wapping management team took place in California and Hammond and his national officer Tom Rice stayed at the famous Beverly Hills Hotel, Los Angeles, at Murdoch's expense. Again, the committed Left heaped abuse upon his head when his luxury hideaway was discovered by this reporter. I discovered him and his colleague under a palm tree, both wearing white shorts. They were not pleased to see me and failed to assist me in my inquiries. The fact that I worked for Bob Maxwell's Daily Mirror may have had something to do with their unpleasant attitude.

If the miners' leader Arthur Scargill was the authoritative voice of the revolutionary Left, Hammond was certainly the unofficial custodian of the views of the committed Right. Although hissed, booed and catcalled on his way to the rostrum at conference time, Hammond appeared to relish every moment of the vilification and abuse heaped upon him by hostile delegates.

Quite simply, he thought he was in the right on vital issues and claimed that most subsequent events vindicated his position. Yes, he was arrogant, but only in a cheeky, mischievous, schoolboy way. It was difficult to dislike him even when you were on the receiving end of his displeasure. But he always remained unruffled and unapologetic, with that Pickwickian gleam behind his spectacles, his half-cockney voice full of scathing, often unprintably amusing comments.

He did not court the favour of journalists but was willing to assist any scribe genuinely seeking the truth. His attitude to left-wing writers was friendly and polite, with a hint of contempt for their craft and their political stance. He was friends with the industrial editor of the Communist Morning Star when that particular organ was denouncing him as the Antichrist. When it came to verbal joustings, particularly with opponents inside or outside his union, he took no prisoners when detailing the harsh realities of adopting an alternative course.

His nerve did not break when he knew the TUC was about to expel his union in 1988 over single-union deals and he cheekily paid £75,000 of affiliation fees "for the honour of being kicked out". He was so sure of the TUC verdict that he only booked two nights for his delegation at a Bournemouth hotel. After his expulsion he left the conference centre and threw his delegate's identification card in the air. It was caught, some would say appropriately, by the industrial editor of The Sun newspaper, which called him "Eric the Lion Heart"

He was a keen supporter of the National Economic Development Office (NEDDY), chairman of its Electronic Components and Technology Sector group. He served on the Industrial Development Advisory Board, the Advisory Council on Energy Conservation, the Monopolies and Mergers Commission and the Engineering Council. He was appointed a member of the Lord Chancellor's Advisory Committee on Legal Education and Conduct and was awarded the OBE in 1977.

Perhaps his best epitaph is the one he humbly gave to himself in his autobiography: "Gladiator".

Terry Pattinson

Eric Albert Barratt Hammond, trade unionist: born Northfleet, Kent 17 July 1929; General Secretary, Electrical, Electronic, Telecommunication and Plumbing Union, 1984–92; OBE 1977; married 1953 Brenda Edgeler (two sons); died 30 May 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks