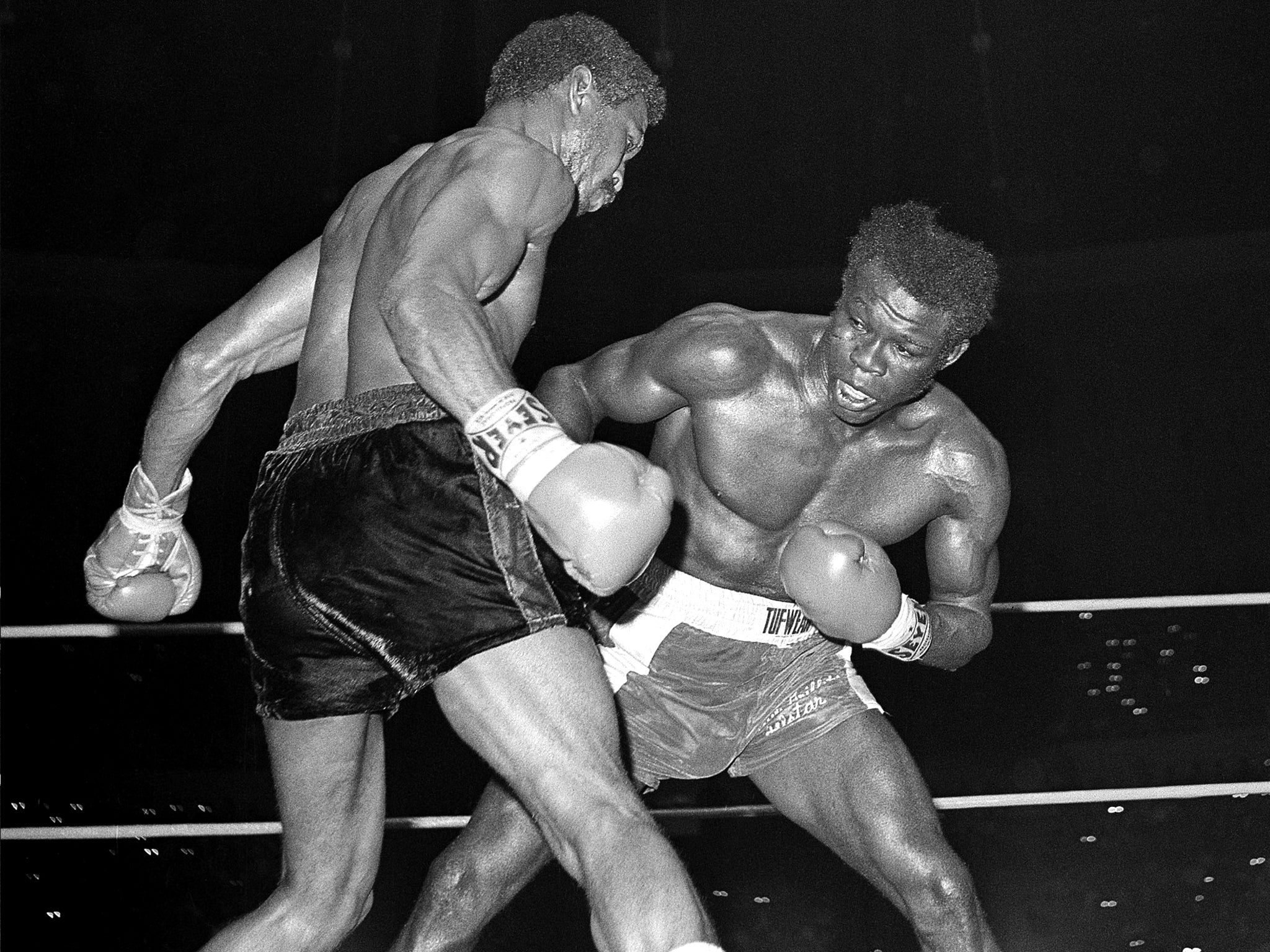

Emile Griffith: World boxing champion whose career was overshadowed by his sexuality

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Emile Griffith's audition to become a fighter took place in a bustling New York street when a couple of boxing insiders asked him to strip to his trousers, turn and flex his muscles. At the time Griffith, a teenager émigré from the Virgin Islands, was delivering bundles of women's hats to wholesalers in the city's garment district.

A few months after the semi-naked inspection Griffith, who had never previously been near a boxing ring, entered the 1957 New York Golden Gloves tournament and launched his truly remarkable and often tragic career as a boxer. His days as a milliner's assistant were over.

Griffith is now recognised as one of the greatest fighters in history for his wins and losses in the prize ring. However, his ambiguous sexual identity and preferences came to dominate, and in many ways eclipse, his ring achievements. Ten years ago he finally admitted to sleeping with both men and women; he was never openly gay, a word he hated until the end of his life. He fought 112 professional fights, winning and losing world titles at three different weights in classic and unforgettable meetings with the very best fighters during 19 years between the ropes. He won 85 times, took part in 24 world title fights, which were spread over a stunning 15-year period, and finally retired after a defeat in Monte Carlo to Alan Minter in 1977.

His ultimately tragic trio of fights with the volatile Cuban, Benny "Kid" Paret, for the undisputed world welterweight title, defined Griffith and left him forever victim to his ring guilt. In April 1961 Griffith took the title in a bad-tempered brawl that ended abruptly when he knocked out Paret in the 13th round. The rematch a few months later was equally hostile and Paret gained revenge on points. There had been some insults and it is thought that it was before this fight that Paret first referred to Griffith as "maricon", the Spanish for "faggot", as Griffith would tearfully explain. The third fight had to happen; it was boxing's biggest match-up at the time.

In March 1962 Madison Square Garden was the venue for the grudge match. The weigh-in for the fight, probably the most famous in boxing history, was vicious. "He called me 'maricon'. I knew what it meant," Griffith said. "He was nude on the scales and he was right up on me. I was ready to punch him." Paret also placed his hand on Griffith's naked back. Griffith would later explain that he knew Paret had been put up to it and that it was not personal. Sadly, a few hours later in the Garden ring it was personal.

Griffith was dropped in the sixth round; Paret laughed and placed his hand on his hip in a wildly provocative move during the eight count. Gil Clancy was in the corner, as he had been for every fight before and would be for every fight after that fateful night. Clancy told Griffith that when he hurt Paret to just keep on hitting him. Boxing is savage, and the men that shape its history make no apologies for its barbarity.

Griffith furiously backed Paret into a corner in round 12. The veteran referee Ruby Goldstein was too far behind the fighters, and Griffith opened up. The fight was live on television and the repeats were shown far too often. Paret slumped as 17 punches connected with his head in five seconds. Goldstein, who would never work again, finally intervened as Paret collapsed. Ten days later Paret died, the rivalry was over and the demons had kicked in.

"I'm as much to blame as the ref," claimed Clancy. "I told Emile to keep throwing punches." Paret had lost a world title fight at middleweight a few months earlier and had been dropped three times and stopped in 10 rounds, which was crucially considered a factor in his death. The ruinous previous fight offered a distraught Griffith little solace.

Griffith kept fighting and winning world titles; his victory for the middleweight version in 1966 against Dick Tiger was a master class. His three world title fights with Italy's Nino Benvenuti remain classics and his 1973 loss to Carlos Monzon, arguably the greatest middleweight ever, was most probably crooked. Mickey Duff, the British fight figure, was in Monte Carlo on the night, mingling with officials at the end of the fight, and he told Clancy and Griffith that they had won. There was a long delay before the 15-round verdict went to a sheepish Monzon.

Clancy finally persuaded Griffith to retire after the Minter loss and the boxer started to train fighters. He was in Bonecrusher Smith's corner at Wembley in 1984 when Frank Bruno lost for the first time. Retirement, however, was difficult for Griffith as he struggled to fight the twin evils that assault too many great boxers: the onslaught of dementia and the disappearance of money.

The debate over Griffith's sexuality was at the centre of the news once again in 1992 when five thugs attacked him after he had left a gay bar in New York. He was 54 and took a severe beating but still made it home on the train with multiple injuries which required him to spend four months in hospital. His attackers were never captured and Griffith never recovered, his ring damage worsened by the blows from the coward's baseball bats.

"I don't remember a lot of the fights," Griffith told me in 1998. "Don't worry," I assured him, "we will remember them for you."

Steve Bunce

Emile Griffith, boxer: born Virgin Islands 3 February 1938; 112 professional fights (won 85, lost 24, drew two, one no-contest); world champion at welterweight, light-middleweight and middleweight; died New York 23 July 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments