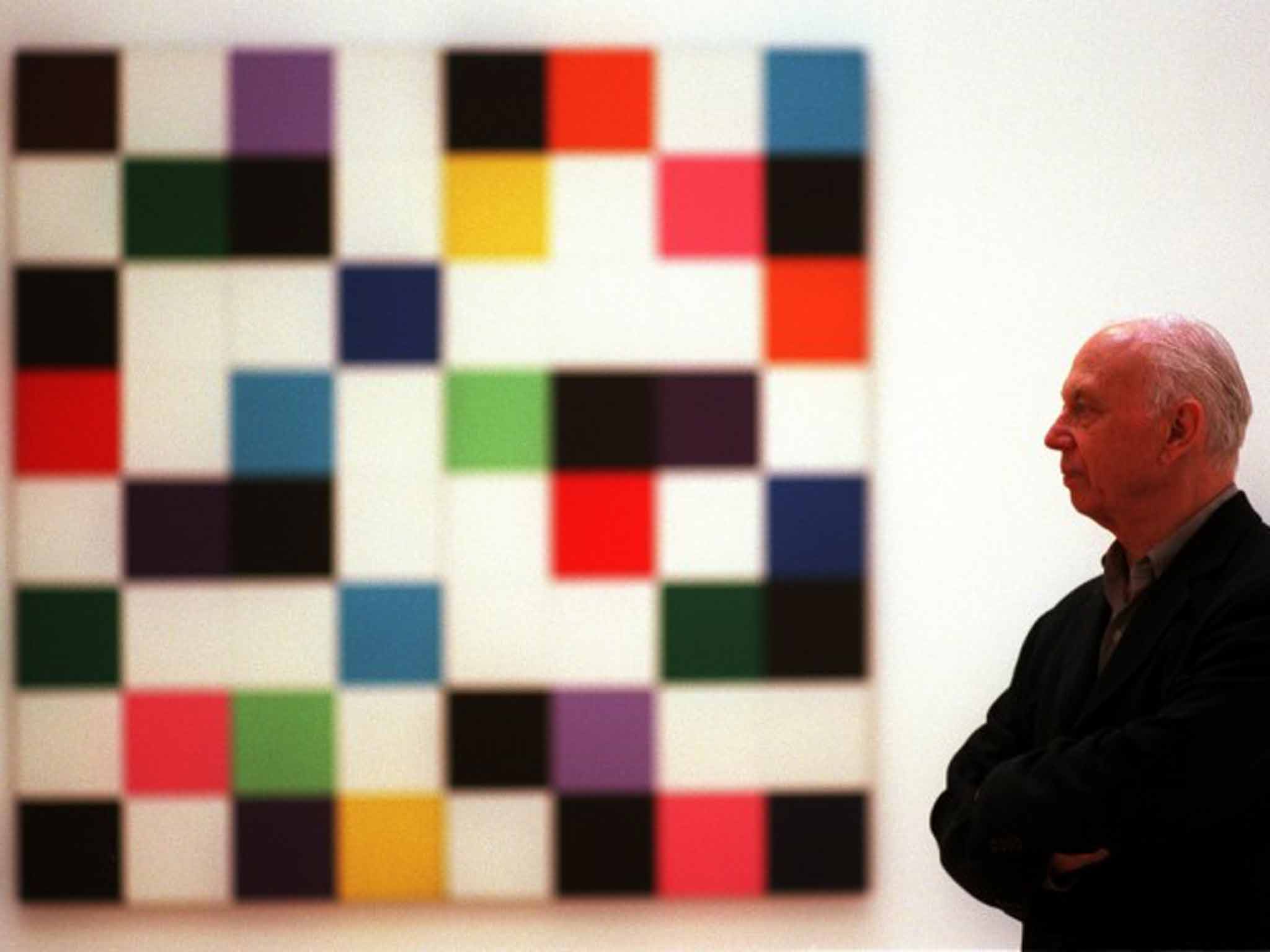

Ellsworth Kelly: Artist who pioneered the style known as hard-edge abstraction

Deceptively simple, Kelly's work was, in reality, infinitely painstaking

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In May 2013, an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York reunited a suite of 14 canvases not seen together since Ellsworth Kelly had painted them four decades before. Kelly was nearing 50 when he made the works, known as the Chatham Series, for the town where he had recently moved his studio, in 1971; the show at MoMA was to celebrate the artist's 90th birthday. Dapper, bespectacled and trailing an oxygen bottle – six decades of inhaling turpentine had affected his lungs – Kelly eyed the two-colour, upside-down Ls of the series with an appraising eye. “I'm quite impressed with them,” he said, after a pause. Then: “It's always a mystery looking back.”

There was a great deal to look back on. Born not far from Chatham, in the Hudson-side town of Newburgh, Kelly had lived all but 20 of his 90 years in New York state. In later life, he would put his interest in colour down to a childhood spent bird-watching in local pine woods. “I recall, as a kid, following a black bird with red wings,” he said. “He was leading me on, into the trees. In a way, that little bird seems to be responsible for all my paintings.”

It was the two decades spent outside America that shaped Kelly as an artist, however. After brief periods spent at American art schools and wartime service in the so-called “Ghost Army” deception unit in Normandy – “We made inflatable dummies of tanks and then waited for the Germans to see them,” Kelly said, mildly – he used a GI Bill grant to move to Paris and the École des Beaux-Arts in 1948.

Part of an American group there that included John Cage and Merce Cunningham, Kelly was more clearly influenced by a trio of Europeans. From the wood reliefs of Jean Arp, he learned that painting and sculpture need not be separate. The two-part Ls of the Chatham Series were still exploring the interrelation of space and colour a quarter of a century later. From Brancusi, he took an economy of form that stayed with him for the rest of his life. Most important of all, Mondrian's Neo-Plastic rectangles shaped the kind of work for which Kelly would later become famous, a style known as hard-edge abstraction. By the time he returned to America in 1954, Kelly had, as he put it, “already figured out my style of painting.”

It was a difficult moment for an artist intrigued by formal relationships to arrive in New York. (He had nearly done so without his work. He wired his parents from Paris for $200 for his fare and another $200 to ship his paintings, but they sent only enough for his ticket. Kelly used the money to send his canvases ahead, then worked his way across the Atlantic.) By 1954, Abstract Expressionism had taken hold in the city, led by its paint-flicking mastermind, Jackson Pollock. Pollock's art could not have had less in common with that of Ellsworth Kelly.

By luck, the newly returned painter took a studio in Coenties Slip, now in the heart of Manhattan's Financial District but then a collection of decaying warehouses near the East River. Kelly found himself working alongside Agnes Martin, a Canadian-American painter whose Minimalist interests chimed with his own. A decade older and, like him, gay, Martin took the young Kelly under her wing, introducing him to her gallerist, Betty Parsons.

In 1956, Kelly had his first one-man show at Parsons' gallery. The work he showed there, with each of its blocks of pure colour contained on its own discrete sub-section of canvas, was entirely unlike the wild-eyed, macho mark-making of Pollock and his kind. It brought Kelly instant fame. Like the images he made, his subsequent career was one of orderly progression. In 1956, Kelly was included in the epoch-making show, Sixteen Americans, at the Museum of Modern Art. (MoMA would remain a temple to his work. When the rebuilt museum reopened in November 2004, there were only two objects on its ground floor: a Rodin sculpture and an Ellsworth Kelly painting.) This was followed, the next year, by the Whitney's Young America 1957, and then, in 1962, by Towards a New Abstraction at the Jewish Museum.

Critics of the Whitney show had been alarmed by the straight lines and separations of Kelly's Painting in Three Panels, missing its nods to Classical friezes and Byzantine murals. By 1962, though, it was clear that his work was the harbinger of something new. From Kelly would descend a line of minimal and geometric artists that included Donald Judd, Carl Andre and Frank Stella, and, across the Atlantic, Bridget Riley.

Financial success allowed Kelly to move his studio, in 1970, from Manhattan to the disused theatre in Chatham where the eponymous Series was made the following year. If he had already begun to experiment with irregularly shaped paintings – trapezoids, triangles, canvases with curved edges – the new studio allowed him to make much larger work.

If Kelly owed any debt to Pollock, it was in the older man's understanding of the power of scale, an American sublime. There the similarities ended, though. Where Pollock's drips and splashes made a fetish of the artist's hand, Kelly's unmodulated blocks of colour did everything in their power to deny it. That hand was there, though, and in a much more insistent way than Pollock's had been.

Deceptively simple, Kelly's work was, in reality, infinitely painstaking. (“People say, 'Your work is very simple, you are taking too much away',” he laughed. “I say, 'No, I don't put it in to begin with'.”) A typical canvas called for layer upon layer of underpainting, so that the saturated colour of its surface was drawn from the depths of the pigment beneath it. Kelly's art, like his life, worked from the outside in, shunning the influence of contemporaries, engaged only with itself.

When he moved his studio upstate from Manhattan, Kelly had also removed himself. From 1970, he lived in Spencertown, not far from Chatham. From 1984, he shared his new house with his partner, Jack Shear (a photographer, Shear now runs the Ellsworth Kelly Foundation.) In 2005, the pair moved to a clapboard Colonial mansion on its own estate, with the architect, Richard Gluckman, adding a 15,000 square foot studio. Here, by natural light from glazed panels overhead, Kelly spent his mornings working in silence.

Along with his trademark multi-part, two-colour canvases, he produced unexpected things – figurative portraits and nature studies in black ink, industrial-looking sculptures. If Kelly took inspiration from any other artists, they were mostly long dead: the work on his studio walls included a Matisse, a Bonnard and a Picasso. In an era of Ed Ruscha and Jeff Koons, he remained true to himself, and successful in spite of it. “I am an abstractionist,” he said, philosophically, “and abstraction is not what people are doing today.”

When Kelly had visited Joan Miró in Majorca in the early 1950s, the ageing Spaniard had complained, “What's going on in New York? Pollock, Rothko – people are forgetting about me!” Shocked, Kelly had denied it. At 90, he admitted to understanding the old man's frustration. “Miró taught me something,” Kelly said. “As you get older, you find yourself watching the young.” For all that, he remained content. “Who wants heaven?” Kelly asked. “When you get to 90, you have to accept it. This has been my life. It is what it was. I put everything into it that I could.”

Ellsworth Kelly, artist: born Newburgh, New York 31 May 1923; Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres 1987, Commandeur 2002; partner to Jack Shear from 1980; died Spencertown, New York 27 December 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments