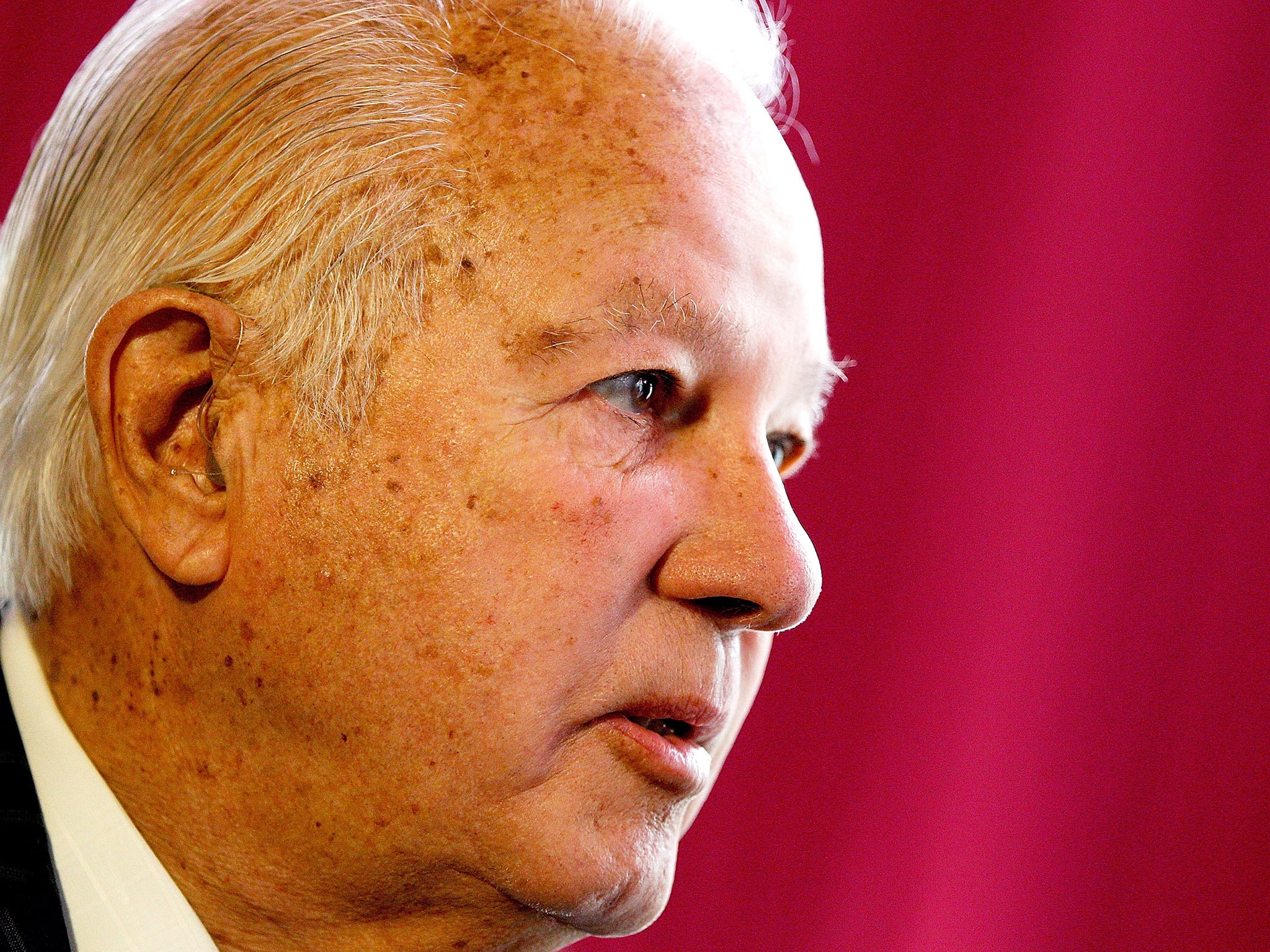

Edwin Edwards: Colourful American governor with a penchant for theatrics

His accomplished, but controversial, career in politics was tarnished by spell in prison for corruption

In Louisiana, a state notorious for colourful politicians, Edwin Edwards blazed for half a century, a near-perpetual neon rainbow. The former Louisiana governor and US congressman, who has died aged 93, was a brazen practitioner of the corrupt-politics-as-theatrics style mastered by the legendary Depression-era demagogue Huey Long.

Edwards served three full terms in the US House of Representatives, four terms as governor and, starting in 2000, eight years in federal prison for racketeering, extortion and related crimes. He staged an unsuccessful political comeback in 2014, running once again for a House seat, and was quick-witted and resilient even at the lowest points of his career.

He could joke about being sentenced to prison, at age 73. “The government asked the judge to sentence me to life or 35 to 40 years,” he recalled. “I said I’d take life, it’s shorter.” The judge, he added, “didn’t see the humour in that.”

He gambled prodigiously. He boasted of chasing women half his age; he met his third wife, who was 51 years his junior, through a prison correspondence. He wore his hair, which turned silver, in the smooth pompadour of a televangelist.

His lovable-rogue persona tended to overshadow genuine achievements. He was credited with helping to shape the modern Democratic Party by advocating racial inclusiveness and with streamlining Louisiana’s outdated government. The Superdome sports arena opened on his watch as governor in 1975.

In the 1991 gubernatorial runoff election, a shrewd Edwards campaign contributed to the crushing defeat of then-state representative David Duke, the former Ku Klux Klan grand wizard, whose rise as a national symbol of white anger was brought to a halt.

In that race, Edwards employed his trademark humour to good effect. His supporters printed bumper stickers that read, “Vote for the Crook. It’s Important,” alluding to unsuccessful attempts to prosecute him on corruption charges. And he joked roguishly that he and Duke were both “wizards under the sheets”.

Edwards was a throwback to a far more permissive era in bayou politics, a time when Louisianans were much more tolerant of politicians who transformed excess into performance art.

Lawrence Powell, a history professor emeritus at Tulane University in New Orleans, calls Edwards “the last of the buccaneer liberals who governed in the tradition of Huey Long. They were characterised by a redistributionist politics, where you could always see progress in lifting people out of poverty – but it was linked to easy political morals.”

Edwin Washington Edwards was born 7 August 1927, in Avoyelles Parish, where the Bowie knife was invented and Cajun music filled the air. His father was a half-Cajun sharecropper; his mother was a French-speaking Cajun midwife.

Edwards started life as a Catholic, but as a teenager, he converted to the Church of the Nazarene. He preached to local congregations, giving him early practice in commanding a crowd.

After brief service in the naval air corps, he graduated from Louisiana State University in 1949 with a bachelor’s degree in law. He settled in Acadia Parish, where he practiced law and got his start in politics, winning election to the Crowley City Council in 1954.

In Crowley, Edwards’s French skills made him a more effective attorney for Cajuns, and he developed a reputation as a defender of minorities and the poor, constituencies he would rely on – and advocate for – throughout his political career.

In 1949, he married Elaine Schwartzenburg, with whom he had four children; he also converted back to Catholicism around that time.

After serving on the Crowley City Council for a decade, Edwards was elected to the state Senate, where his grasp of issues, smooth oratory and good looks marked him for bigger things. In 1965, he won a special election to fill the vacancy created by the death of representative T Ashton Thompson in a car accident.

Edwards easily won three subsequent House elections. In Washington, he was one of the only southerners to vote for an extension of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, a landmark civil rights law.

In 1976 – four years after he left the House – he was briefly ensnared in a congressional bribery and influence-peddling scandal involving South Korean businessman Tongsun Park.

Edwards admitted to reporters that Park had once given Elaine Edwards an envelope containing $10,000 in cash, but he insisted that it was just a gift from a friend. He was not charged in the scandal, and it caused barely a ripple in his political career.

Edwards was first elected Louisiana governor in early February 1972, defeating Republican David Treen in the third round of a three-round process that began the previous November. Over the years, Edwards’s popularity swelled and deflated with the state’s economy. During his first and second terms, Louisiana’s gas and oil tax revenue kept state coffers flush, in part because of changes in the tax code that he pushed through.

In 1973, he made what might have been his most lasting contribution when he oversaw the rewriting of the state constitution. The new version, adopted in 1974, streamlined a sprawling labyrinth of boards and commissions and ushered in a more modern era of government.

Edwards also championed a new “open primary” election system in which all candidates participate in the same primary, regardless of political party. The system, designed to help Edwards, may have contributed to the victory of the Republican candidate, Treen, in 1979 as several Democrats split the vote in the first round. Edwards was barred from seeking a third consecutive term that year.

Another of Edwards’s achievements was the completion of the Superdome, the huge domed stadium complex in downtown New Orleans. During its construction, costs soared, and Edwards helped persuade the legislature to pour additional millions of dollars into the project.

After the term-limited Edwards sat out the 1979 election, he returned to the fray in 1983 and handily defeated the incumbent, Treen. He boasted during the campaign that the only way he could lose was “if I’m caught in bed with either a dead girl or a live boy”, a phrase probably coined by Texas journalist Larry L King years before Edwards popularised it.

The new term was marred by state budget shortfalls as oil prices plummeted. Then came his indictment on corruption charges in 1985, when he was accused of taking kickbacks from companies dealing with state hospitals. The charges stemmed from a partnership he formed between his second and third terms as governor – a business enterprise from which he made about $2m.

The trial turned into a circus, with Edwards as the ringleader. He rode a mule-drawn cart to the courthouse to protest the pace of the proceedings, and he held lively news conferences every afternoon. Edwards was acquitted in 1986, but details of Las Vegas gambling trips that emerged during the trial, combined with the state’s dismal finances, sank his popularity.

He ran for a fourth term in 1987, campaigning on legalised gambling as a means to turn around the economy. After coming in second to Democratic reformer Buddy Roemer in the primary, he withdrew from the race – thus protecting his record of never losing an election – and Roemer succeeded him.

Although many predicted that his political career was over, Edwards won a final term in 1991 – running against Duke, the former Klansman – mostly because he was widely perceived as the lesser of two evils.

Once he was out of office, Edwards’s luck ran out. In 2000, he was convicted on 17 counts of corruption and fraud stemming from kickbacks he received for riverboat-gambling licenses – in one instance, a suitcase stuffed with $400,000 in cash from the former owner of the San Francisco 49ers. (Edwards’s son Stephen and several other associates were also convicted.)

Edwards served eight years of the 10-year sentence and emerged from a halfway house in 2011, in time for his 84th birthday. Then, he wed 32-year-old Trina Grimes Scott, his third wife, who had been his pen pal while he was in prison. Edwards’s first marriage, which lasted 40 years, and his second, to Candy Picou, ended in divorce.

The irrepressible Edwards ran for Congress one last time in 2014, losing a runoff election to Republican Garret Graves by nearly 25 percentage points. But he seemed no less disheartened than he had after his release from prison.

“As you know, they sent me to prison for life,” he told the audience in 2011 at a rice festival in Crowley. “But I came back with a wife.”

Edwin Edwards, politician and former governor of Louisiana, born 7 August 1927, died 12 July 2021

© The Washington Post