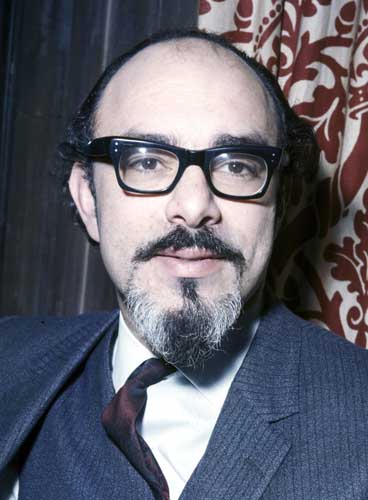

Dr David Kerr: Labour politician who juggled his duties in the Commons with the demands of his medical practice

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One of the most horrendous moments of my life was one morning before 9.30 in 1965 when the ICI chairman, Sir Paul Chambers, had authorised MPs (whom he had accused of being unfit), to use the squash courts in the basement of ICI's Millbank headquarters. My squash partner, opponent, and friend, Dr David Kerr, the MP for Central Wandsworth, collapsed in a heap on the court. For a dreadful moment, I thought he had died; squash for those over 40 could be a killer. To my relief, he picked himself up, told me to go to the shower room to fetch the glucose and needle which he always carried with him, and injected himself. Minutes later he was better, having resolved his hypoglycaemic problems.

A more sensible, cool and collected person is difficult to imagine. All too briefly, from 1964-70, Kerr was a Member of the House of Commons. Of all medical doctors whom I knew over 43 years in the House, none brought a better knowledge of practical medicine and the workings of the health service, other than, perhaps, the present independent member for Wyre Forest, Dr Richard Taylor.

David Kerr's antecedents were mostly Russian Jews. His father, Myer, would tell him that the Tsar's secret police were not nice to the cultured and commercially successful Yiddish community in Minsk; Fiddler on the Roof was a Kerr favourite. His mother, Paula, was one of many Horowitzes endowed with outstanding musical talent and dexterity. They sent Kerr to Whitgift, a public school in Croydon, where Jewish boys thrived. Kerr spent the war at the Middlesex hospital medical school, winning in 1941 the Royal College of Surgeons' MacLoghlin scholarship. During the Blitz and later, he served in the London ambulance service during attacks by V1s and V2s.

Kerr was rejected by the RAF for national service on account of his diabetic condition. On qualifying he joined a practice in Tooting and came to the attention of Dr David Stark Murray, then a considerable figure in the Labour Party, and on Conference platforms. In 1957 Stark Murray was instrumental in his being chosen as honorary secretary of the Socialist Medical Association, a position he held from 1963-1972, when for the next nine years he became vice-president.

In 1958 he was elected to London County Council as a member for Wandsworth. Subsequently he was selected as the Labour standard-bearer for Wandsworth Central – a seat that neither he nor Labour headquarters expected to win. The sitting member was Michael Hughes-Young, who had been Conservative deputy chief whip since October 1959. Kerr won by 20,581 votes to Hughes-Young's 18,336, with Ronald Locke gaining 4,369 for the Liberals. It was one of the victories that allowed Harold Wilson to become Prime Minster with a wafer-thin majority.

On 9 November 1964, before he made his maiden speech, Kerr asked a parliamentary question: "What about the unprecedented need for occupational health services for the House of Commons? Would the minister take an early opportunity to inspect the present facilities available, in company with an expert on occupational health services, and acquaint himself with the fact that the only means of keeping the House going is a copious supply of cascara tablets?"

If the House of Commons developed medical care, it was largely because of Kerr's efforts, arriving as he did to be shocked by a level of medical provision which he said would be unsatisfactory in any factory in the land. Now there is a full-time doctor available in the House of Commons – but in 1964 Kerr spent a great deal of his time ministering to the emergency medical needs of his parliamentary colleagues of all parties.

I remember well Kerr's maiden speech on 17 November 1964. He chose to make it on the subject of the problems of immigrants, and particularly those who went as students to the Balham and Tooting College of Commerce; Kerr argued the case for full-time welfare officers. It stuck in my mind as a Scot that in the course of the speech he said: "Our immigration problems – and I say this meaning no offence to anybody in or out of the House – are contributed to as much by immigrants from Scotland and the north-east of England as from Jamaica. I have often felt that if all Scotsmen wore their kilts there would soon be a 'Keep Britain Trousered' movement."

Kerr ended up by saying that it had been his pleasure for six years to share the benches in County Hall with an able, courteous, intelligent, forthright and conscientious member of the council who was a West Indian. He wondered if it was too much to hope that in the not-too-remote future we should accept on the Labour benches somebody of similar origin, who would make similar valuable contributions to the work of the House. Kerr always believed that the sooner immigrant minorities were represented in the House of Commons the better.

One of his many medical campaigns concerned cervical cancer. Others concerned dental health, doctor's accommodation for good practices, treatment of epileptics, children in care, smoking in cinemas, homosexual offences, prostitution and illegitimacy. On 12 February 1965 he was the first MP ever to initiate an adjournment debate on illegitimacy. I remember him telling the House that in Britain as a whole in 1962 there were just over 60,000 illegitimate children born; in 1963 over 64,000; in 1964 it was estimated that there would have been born 68,000.

Kerr was compassionate and put forward a number of constructive proposals as to how to improve society's attitude to the illegitimate. On behalf of the Home Office Alice Bacon thanked him for raising an important problem, causing great concern to all responsible local authorities, social workers and parents.

In 1966 Judith Hart, then a rising star in the Wilson government and Minister of State of the Commonwealth office, chose her fellow left-winger Kerr as her ParliamentaryPrivate Secretary. It looked as ifhe would be on course for a ministerial career. But it was not to be. Heindicated that he would not be standing at the next general election. This was partly because of seat redistribution in Wandsworth and the creation of a new constituency in Tooting.But more importantly, he had told his medical-practice partners that he would do only five years, and if it turned out to be more he would resign from the practice. Kerr told me cheerfully "I think that I am a better doctor than politician!"

He was a highly respected general practitioner in Tooting, juggling being a Councillor and MP at the same time. Much loved by his patients, he retired in 1982 and became chief executive of Manor House Hospital – the trade union hospital – from 1982 to 1987. Moving out of London to Welwyn Garden City, he served on Hertfordshire Council from 1989 to 2001. His energies for the service of his fellow human beings were prodigious.

Tam Dalyell

David Kerr, doctor and politician: born 25 March 1923; Secretary, Socialist Medical Association, 1957-63, vice-president 1963-72; Councillor, London County Council for Central Wandsworth 1958-1963; Councillor, London Borough of Wandsworth, 1964-68; Labour MP, Wandsworth Central, 1964-70; Private Parliamentary Secretary to Minister of State, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 1967-69; Governor, British Film Inst., 1966-71; Visiting Lecturer in Medicine, Chelsea College, 1972-82; Director, War on Want, 1970-77, Chairman 1974-77; Chief Executive, Manor House Hospital, London, 1982-87; Councillor for Welwyn Garden City, Hertfordshire County Council, 1989-2001; married 1944 Aileen Saddington (marriage dissolved 1969, two sons, one daughter), 1970 Margaret Dunlop (one son, two daughters); died Ware, Hertfordshire 12 January 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments