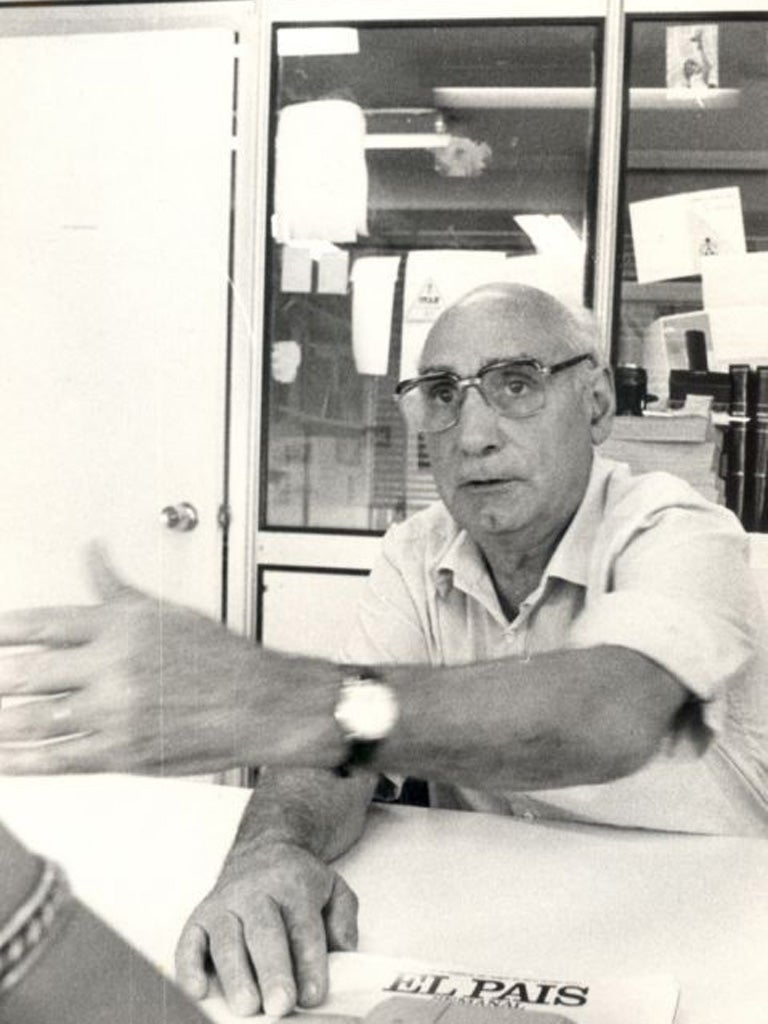

Domingo Malagon: Master forger for the anti-Franco resistance

'Many of us owe our freedom to him,' a leader of the Communists said,' and some of us our lives'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is testament to Domingo Malagon's innate modesty that he never liked the way leading 1950s Spanish Communist Party [PCE] colleagues called him the one "irreplaceable element" in their organisation. But as the top document forger in the main segment of Spain's anti-Franco resistance movement for over three decades, if anybody deserves that description, it was surely Malagon.

For those PCE members needing fake passports, identity cards or safe conducts to dupe General Franco's security forces or simply to travel undetected through the rest of Europe, from the earliest maquis, or guerrilla groups, in the 1940s through to the Communists' extensive network of clandestine factory or dockyard cells in the '60s and '70s, a document from Malagon's secret workshop in Paris proved more than sufficient.

Malagon created thousands of false identities over the decades, his work easily surpassing possibly its biggest challenge, a newly designed identity card for all Spaniards in 1951, which the dictatorship-controlled media boasted was impossible to fake. Malagón knew better. Among his more famous "clients" were leading PCE members like Dolores Ibárruri, known as "La Pasionaria" for her stirring Civil War speeches, or plain María Pardo in the fake identity card Malagón made for her in 1973. Other key resistance fighters with Malagon documents incudied Jesus Monzon, who co-ordinated the ill-fated anti-Franco invasion of Spain through the Pyrenees in 1944, or Gabriel Trilla, co-founder of the first PCE in 1920. It almost goes without saying that Malagon had his own series of aliases: one of his extant forgeries from the 1960s is his own Argentinian passport.

Malagon's last falsification was arguably his most famous: a passport for the heavily disguised PCE leader Santiago Carrillo, complete with wig, in 1977. That was two years after Franco's death, but the PCE was still illegal, and Malagon's document was the only way Carrillo could get into the country undetected.

Malagon's superb talent for forgery had solid artistic foundations. After losing his father aged two, in 1918, he grew up in La Paloma, an orphanage and old people's home in Madrid, where his mother worked washing clothes. He studied for three years at a Fine Arts college, and had it not been for the outbreak of the Civil War in 1936 would have sat his final summer exams there.

Instead, in July that year Malagó* found himself fighting in the Republican Army's fifth regiment in the sierras near Madrid. Soon afterwards he joined the Communist Party and following a spell in Catalonia in 1938 and the Republic's defeat in 1939, he went into exile in France.

He spent the next two years in concentration camps in southern France. In 1940 he escaped, and began work as a forger for the PCE, first in Perpignan and then in Toulouse. In 1947, he set up a more permanent workshop in Paris, hidden in a house belonging to French sympathisers. "He seems to have a virtuoso talent [for forgeries]" said a PCE internal report in July 1945. "He is both loyal and discreet." By 1950, when Franco allowed Spaniards to travel abroad again, rather than having to use shepherds' tracks across the Pyrenees Franco's opponents could use normal border crossings: the potential for clandestine operations increased enormously, but that made Malagon's documents even more necessary.

However he roundly rejected the idea that he was irreplaceable. "Call it my Stalinist or Leninist indoctrination, or just dogmatism, but I thought everybody was necessary and nobody irreplaceable in our party," he would respond. Others disagreed. "So many of us owe our freedom to him, and some of us our lives," wrote Jorge Semprún, the author who was Malagon's political chief in the PCE for more than a decade, and who entered Spain using his documents several times. "Sometimes I saw him working, almost lovingly handling the inks, the stamps, the plastics and colours... The documents would turn into works of art, comradely safeguards for the possible storms of clandestine life."

Victoria Ramos, PCE member and co-author of a biography of Malagón, told me, "He was barely known, even inside the Party, but without his documents our operations would have been impossible. When I got to work with him [in the 1970s] I found him to be a warm-hearted, exceptional person."

After his return to Spain, Malagon continued working for the PCE, as their internal archivist. He lived in the small town of Parla, south of Madrid, for the rest of his life, and the council there named a street after him in recognition of his major contribution to the struggle for democracy.

Domingo Malagon, political activist: born Madrid 28 November 1916; married 1947 Escolastica Jimenez (one son); died Parla, Spain 30 March 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments