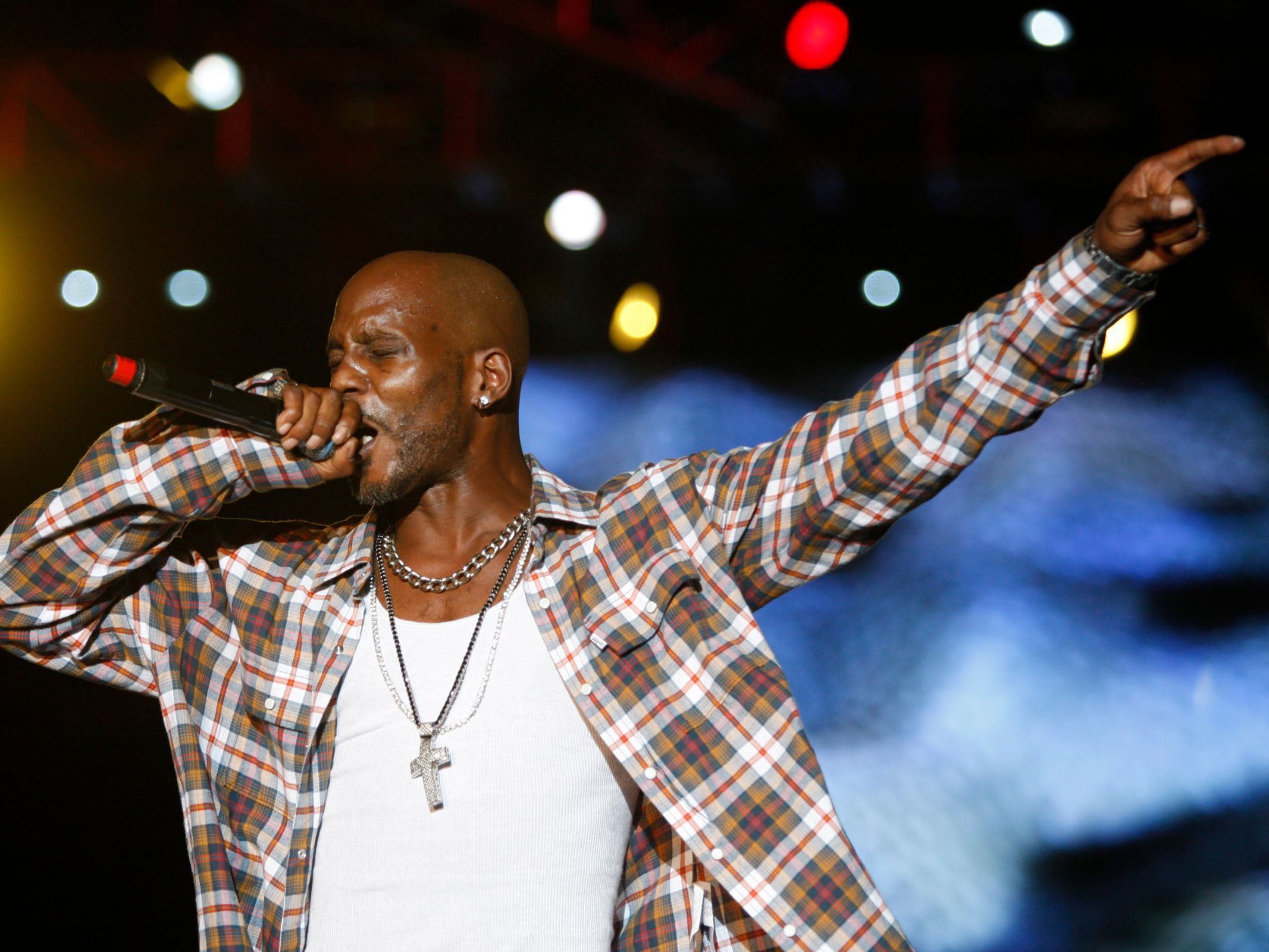

DMX: Rapper who battled adversity and conquered the charts

The American artist delivered rhymes in a growl, punctuated his songs with doglike barks and often wrote about his impoverished upbringing

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

DMX was a gruff-voiced, chart-topping rapper who electrified listeners with songs such as “Party Up (Up in Here)” and “X Gon’ Give It to Ya”, drawing inspiration from his difficult life while also emerging as a star of action films and crime thrillers.

He died on 9 April at a hospital in White Plains, New York. He was 50. DMX, whose real name was Earl Simmons, recorded with artists including LL Cool J and Onyx before releasing his debut album, It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot, in 1998. Featuring singles such as “Ruff Ryders’ Anthem” and “Get at Me Dog” – “I’m just robbin’ to eat/ And there’s at least a thousand of us like me mobbin’ the street” – the album sold more than 4 million copies and established him as a leader of hardcore hip-hop.

Hailed by some critics as an heir to slain rapper Tupac Shakur, DMX delivered rhymes in a growl, punctuated his songs with doglike barks and often rapped about his impoverished upbringing in Yonkers, New York, where he said he began using crack cocaine at age 14, sold mixtapes on the street, and bounced between foster homes and juvenile detention centres.

“Even more than Eminem (who balances his paranoia with a mischievous sense of humour) or Tupac Shakur (who balanced his laments with smooth, swaggering boasts), DMX makes it impossible for listeners to ignore his suffering and desperation,” music critic Kelefa Sanneh wrote in a 2006 article for The New York Times. Rolling Stone declared that his voice was “the sound of gravel hitting the grave”.

DMX later toured with rappers Jay-Z, Method Man and Redman and became something of a hip-hop rock star, performing before a crowd of 200,000 at Woodstock ’99 and releasing the crossover single “Party Up (Up in Here)” the next year: “Y’all gon’ make me lose my mind/ Up in here, up in here.” He became the first artist in the history of the Billboard 200 to reach No 1 with each of his first five albums.

He also moved into acting, appearing in three Andrzej Bartkowiak blockbusters that fused martial arts and hip-hop. After a small role as a nightclub owner in Romeo Must Die (2000), he starred as a drug-dealing computer expert in Exit Wounds (2001), opposite Steven Seagal, and played a jewel thief who partners with Jet Li’s Taiwanese detective in Cradle 2 the Grave (2003).

But his music and film careers were increasingly overshadowed by his legal troubles, including charges of animal cruelty, drug possession and impersonating a federal agent in a bizarre attempt to steal a car. According to a 2019 article in GQ, he went to jail some 30 times. By the time he filed for bankruptcy in 2013, he had 10 children (he later had five more, according to news reports) and owed $1.3m in child support payments.

In an interview that year with motivational speaker and author Iyanla Vanzant, he traced some of his difficulties to a crack cocaine addiction that made him feel paranoid and suicidal. “Just because you stop getting high doesn’t mean that you don’t have a problem, because it’s a constant fight every day,” he said. “Every trigger that was a trigger is still a trigger. Whether you act on it or not is something different. But I will always, until I die, I will always have a drug problem.”

In 2017, he was charged with concealing millions of dollars in income and dodging $1.7m in taxes. He pleaded guilty to tax fraud and was sentenced to a year in prison after Murray Richman, his lawyer, played a recording of DMX’s song “Slippin’” for the Federal District Court in Manhattan, trying to convey a sense of the rapper’s life and music. “They put me in a situation forcin’ me to be a man,” he rapped, “when I was just learnin’ to stand without a helpin’ hand.”

According to a report in the Times, Judge Jed S Rakoff appeared unmoved but later expressed sympathy for DMX. “In the court’s view Mr Simmons is a good man, a very far from perfect man,” he said, rejecting prosecutors’ recommendation for a five-year sentence. “In many ways he is, to give the cliche, his own worst enemy.”

Earl Simmons was born on 18 December 1970, with various accounts giving his birthplace as Baltimore or Mount Vernon, New York. In his telling, he was raised by a single mother who once knocked out two of his teeth with a broom.

He was institutionalised from ages seven to 14 and said he was arrested for the first time when he was 10, for arson. In Yonkers, he befriended stray dogs and started beatboxing for a local rapper named Ready Ron, who encouraged him to write his own rhymes but also introduced him to crack cocaine. “Everything in my life is blessed with a curse,” DMX said last year in an interview with fellow rapper Talib Kweli.

By 1992, when he signed with Columbia Records, he was using the name Dark Man X or DMX, after a digital drum machine. His first single, “Born Loser”, lived up to its title; he struggled to break through before switching to Ruff Ryders/Def Jam Records, which released his 1998 debut album. Later that year he released a follow-up, Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood, with a cover photo that appeared to show him covered with blood.

“I want to say what’s on my people’s minds, soak up all their pain,” he told a Def Jam interviewer. “I’ve learned that when I take it all in, I can make one brotha’s pain be understood by the world.”

Shortly before going on tour in 1998, he was charged with raping a woman he had allegedly met at a strip club. He was later cleared by a DNA test and went on to make his feature film debut later that year, starring alongside the rapper Nas in Belly, a crime film made by music video director Hype Williams.

His later films included Never Die Alone (2004), in which he played a hardened drug dealer named King David. The movie earned only $6m but drew praise from critics such as Roger Ebert, who wrote that it was “not a routine story of drugs and violence, but an ambitious, introspective movie in which a heartless man tells his story without apology”.

DMX starred in a reality television series, DMX: Soul of a Man (2006), and started his own record label, Bloodline. He received three Grammy nominations, including for best rap album with ... And Then There Was X (1999).

In addition to the chart-toppers The Great Depression (2001) and Grand Champ (2003), his later albums included Year of the Dog... Again (2006), which reached No 2, and Redemption of the Beast (2015), released amid a dispute with the record label Seven Arts. DMX called it a collection of “stolen music”.

His marriage to Tashera Simmons ended in divorce. He was engaged to Desiree Lindstrom, but complete information on survivors was not immediately available.

After serving his prison sentence for tax fraud, DMX delivered a prayer at Kanye West’s weekly, concertlike Sunday Service ceremony. He often cited his Christian faith as a source of strength, telling GQ that he prayed before taking to the stage and then again before leaving it. Performing, he said, offered a physical and emotional high that no drug could match.

“Maybe 65 per cent of the time that I get offstage, I’m so emotionally overwhelmed, I just break down,” he added. “Sometimes it’s leaving the stage, it’s just like, ‘Get me to my dressing room. I don’t want people to see me like this.’ I just take a minute for myself and just, I thank Him, I praise Him. And I’m like, ‘Thank you, thank you.’ I’m like, ‘Who am I to deserve this?’ We all bleed the same blood.”

DMX, rapper, born 18 December 1970, died 9 April 2021

©The Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.