Dean Stockwell: Child actor who forged decades-long career

The award-winning star of ‘Blue Velvet’ and ‘Quantum Leap’ hated Hollywood but didn’t quite manage to drop out of acting

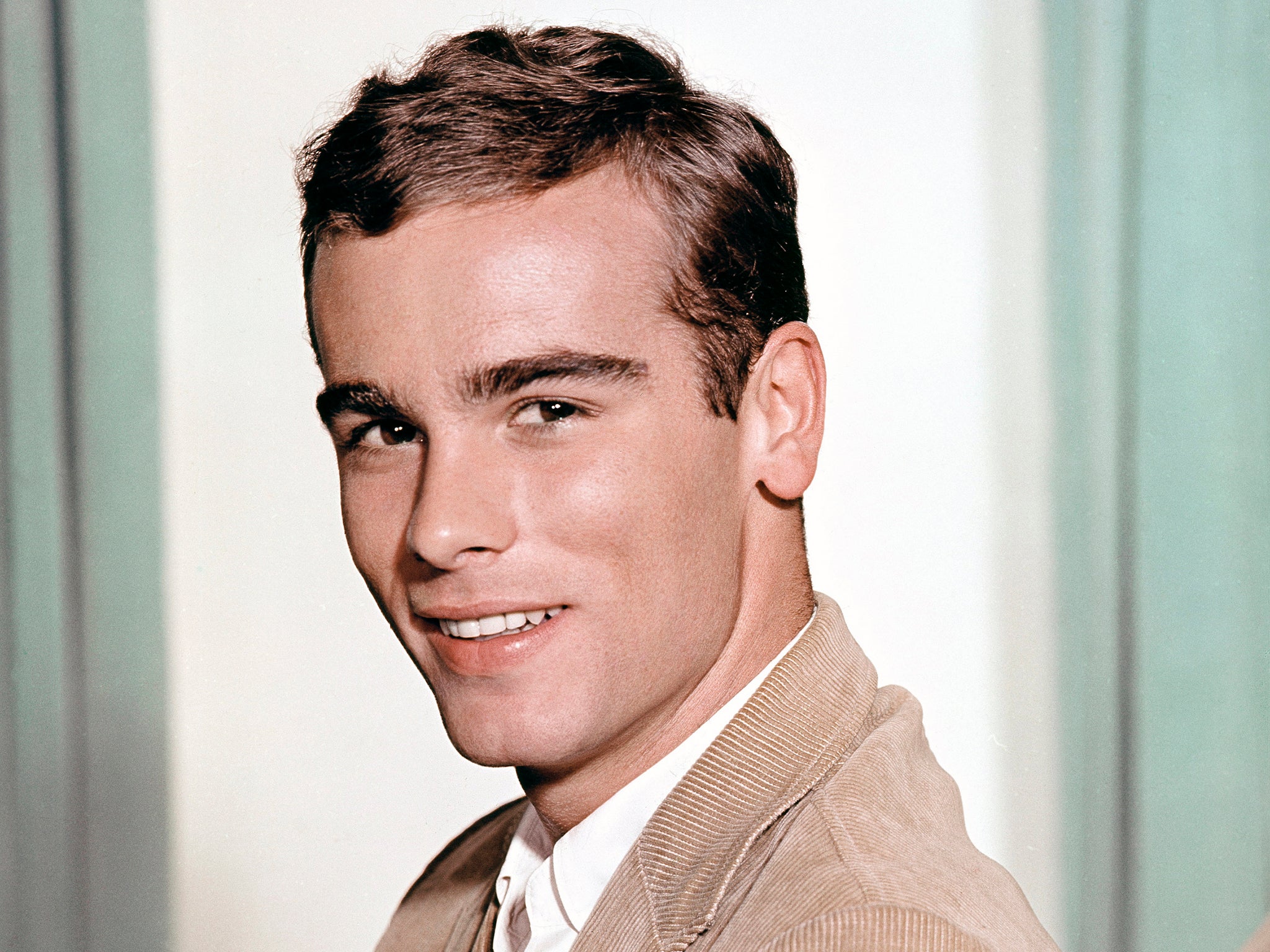

Dean Stockwell, who grew from a cherubic, curly-haired child actor into a charming and occasionally sinister staple of film and television, earning Oscar and Emmy nominations as a lecherous gang lord in Married to the Mob and a cigar-smoking admiral in Quantum Leap, has died aged 85.

Over a sprawling seven-decade career, Stockwell appeared in more than 200 movies and TV shows, working with acclaimed directors such as Wim Wenders, David Lynch, Jonathan Demme, Robert Altman, William Friedkin and Francis Ford Coppola. Raised in a family of actors and entertainers, he made the transition from child star to sensitive young-adult lead, and then from Hollywood dropout to scene-stealing character actor.

His most memorable roles included the mysterious Ben, an apparent drug dealer in Lynch’s neo-noir thriller Blue Velvet (1986), who lip-syncs Roy Orbison’s In Dreams while holding a lamp to his face. “To me it was the high point of the film,” said co-star Dennis Hopper, a longtime friend of Stockwell’s, in an interview with People magazine. “The white make-up, the batting eyelashes – Dean has ways no other actor can touch.”

The character was made up “out of my own demented head”, said Stockwell, who claimed to have created Ben’s outfit and make-up. He told Psychotronic Video, a film magazine, that he sought to bring a similarly “zany” approach to his role on the science-fiction show Quantum Leap, which premiered on NBC in 1989 and ran for five seasons.

Created by Donald Bellisario, the series starred Scott Bakula as Sam Beckett, a physicist who travels involuntarily through time, assuming other people’s identities and correcting mistakes in history. Stockwell received four Emmy nominations for playing Beckett's best friend, Adm Al Calavicci, who appears alongside him as a hologram while offering advice and commentary.

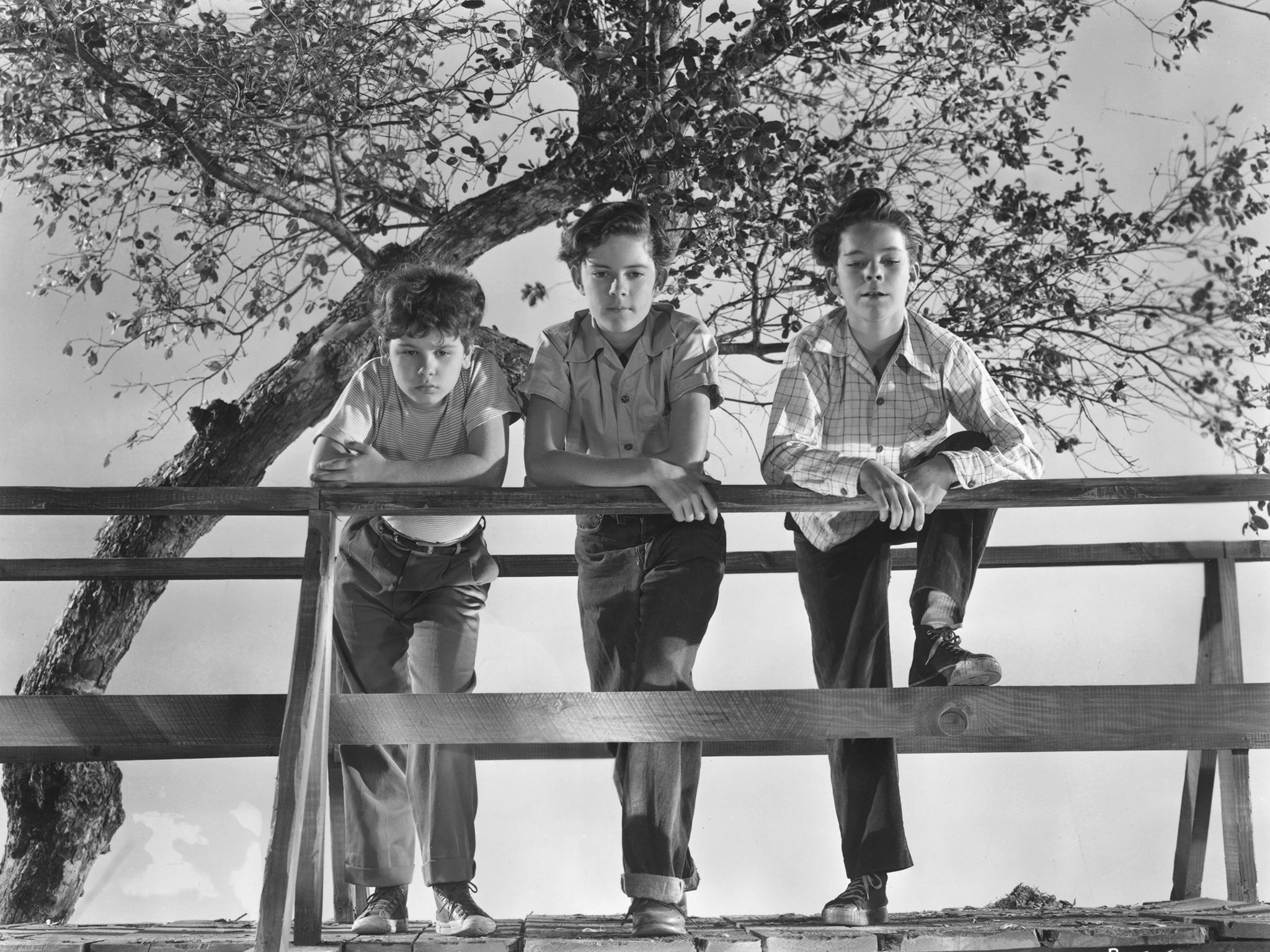

The show was part of an improbable third act for Stockwell, who was one of the rare child actors to work well into adulthood. As a boy, he appeared with Frank Sinatra and Gene Kelly in the musical Anchors Aweigh (1945), received a special Golden Globe Award for best juvenile actor in Gentleman’s Agreement (1947) and played Nick Charles Jr in Song of the Thin Man (1947), the last instalment in the Myrna Loy and William Powell detective series.

But almost from the day he and his family signed a contract with MGM, he hated Hollywood – the loss of his childhood freedom, the endless takes, the dread of having to cry on cue in dramatic scenes. “I couldn’t wait to get pimples. I couldn’t wait to get awkward,” Stockwell later told author and former child star Dickie Moore. “I ruined my posture. I did everything, just to get out of it.”

At the age of 16, he “disappeared into the countryside”, changing his name and working odd jobs for five years before returning to acting because it was the only profession he was trained for. He starred as an introverted killer in the 1957 Broadway play Compulsion, based on a crime novel inspired by the Leopold and Loeb murder case, and reprised the role for a 1959 movie version, with Bradford Dillman as his partner in crime and Orson Welles as the Clarence Darrow-like lawyer who takes their case.

The three stars shared the best actor prize at the Cannes Film Festival, and Stockwell soon landed some of his best roles as a leading man. He played an aspiring artist in Jack Cardiff’s adaptation of DH Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers (1960), which received seven Academy Award nominations, and was honoured again at Cannes for starring in Sidney Lumet’s version of Long Day’s Journey Into Night (1962), alongside Katharine Hepburn, Jason Robards and Ralph Richardson.

Amid the renewed success, Stockwell left Hollywood once again, dabbling in drugs, attending “love-ins” and embracing the hippie counterculture while hanging out with Hopper, Russ Tamblyn and Neil Young in Topanga Canyon. “The Sixties allowed me to live my childhood as an adult,” he later told The New York Times. “That kind of freedom, imagination and creativity that arose all around was like a childhood to me.”

When he started acting again, appearing in B movies such as Psych-Out (1968) and The Dunwich Horror (1970), he found himself embracing his profession for the first time, while also struggling to find roles in mainstream movies. He worked in dinner theatre and, in an act of rage and depression, threw his Cannes awards into the fireplace. By the early 1980s, he had effectively retired from acting, moving to Santa Fe to sell real estate.

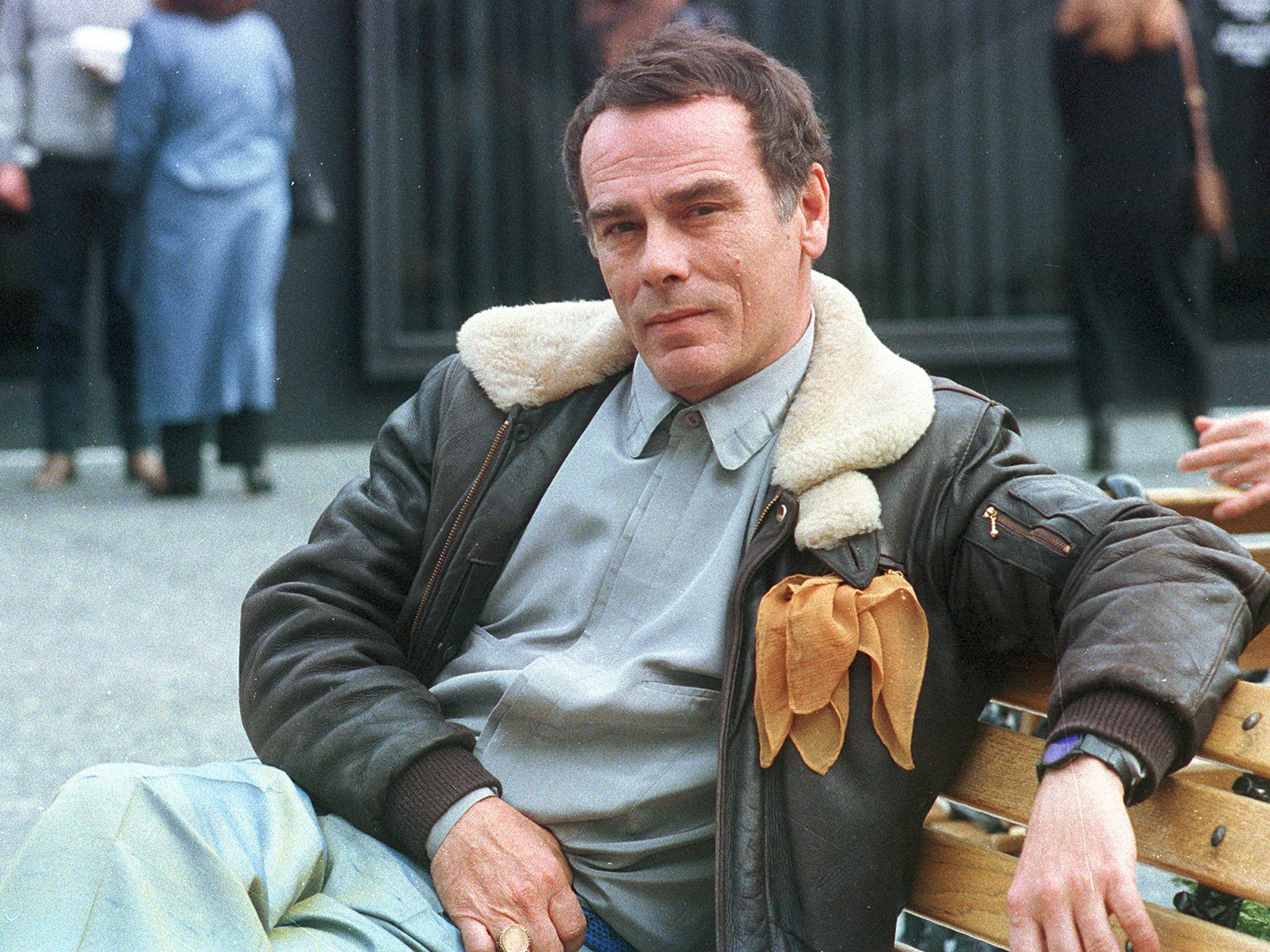

But around that same time, he got a call from Harry Dean Stanton, who invited him to play his younger brother in a road film directed by Wenders and co-written by playwright Sam Shepard. The movie was Paris, Texas (1984), which came out the same year Stockwell appeared in Lynch’s big-budget adaptation of the Frank Herbert novel Dune.

Together, the films kicked off what Stockwell described as his “third career”, in which he played intense and often eccentric characters, including the germaphobic business titan Howard Hughes in Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988). Appearing in the offbeat comedy Married to the Mob that same year, he earned an Oscar nomination for his supporting role as gangster Tony “The Tiger” Russo.

Stockwell also appeared in movies such as To Live and Die in LA (1985) and Beverly Hills Cop II (1987). Late in his career, he starred as a villainous humanoid in Battlestar Galactica, returning to science fiction after the success of Quantum Leap.

“One of my priorities is survival,” he told the Los Angeles Times, looking back on his 1980s revival. “I think that would be a priority for any healthy-minded person, regardless of what their career was, or what it entailed. You want to survive. It ain’t easy. It ain’t easy when you can breathe in stinkin’ air, and the environment is going downhill fast. It just ain’t easy, you know?”

Robert Dean Stockwell was born in Los Angeles on 5 March 1936. His father, Harry, voiced the Prince in Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs; his mother, the former Elizabeth Veronica, performed in vaudeville and took both her sons to an open audition for The Innocent Voyage, leading to their Broadway debuts. Stockwell’s older brother, Guy, continued acting as an adult, appearing with him in an episode of Quantum Leap.

Stockwell launched his film career around the time his parents separated, and said he felt pressure to support his mother and brother by continuing to act.

His marriage to actress Millie Perkins, who starred in The Diary of Anne Frank, ended in divorce. In 1981 he married Joy Marchenko, a textiles expert. They reportedly divorced more than two decades later.

In addition to his wife, survivors include their two children, Austin and Sophie Stockwell.

Stockwell also worked as an artist and dabbled in other aspects of filmmaking. One of his unproduced screenplays, for an apocalyptic, nonlinear film entitled After the Gold Rush, partly inspired Young’s 1970 album of the same name. He later did the album art for Young’s 1977 record American Stars ’n Bars and partnered with the musician to write, direct and star in a 1982 comedy, Human Highway.

But he remained devoted to acting, noting that even when he was a child, frustrated by the long hours on Hollywood sets, there were moments when he felt real joy in front of the camera.

“There’s a feeling that arises when I do something in acting, in a certain way, where it’s right for me, and it’s a very deep-seated satisfaction,” he told Turner Classic Movies in a 1995 interview. “It’s like hitting a 280-yard drive on the golf course. Or like hitting a winner at the track if you’re a gambler. It’s very hard to put a word on it.”

Dean Stockwell, actor, born 5 March 1936, died 7 November 2021

© The Washington Post