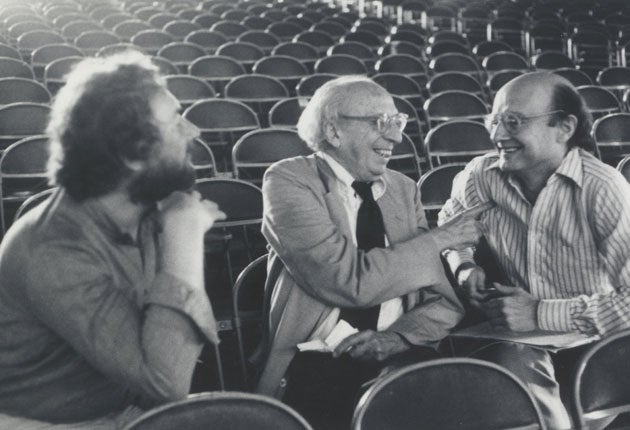

David Drew: Musicologist and authority on Kurt Weill who transformed the fortunes of Boosey & Hawkes

For half a century David Drew stood at the centre of musical life in Britain, as critic, writer, musicologist, editor and publisher. As Director of Publications at Boosey & Hawkes his astute choices of composer conditioned the contents of concert halls around the globe – and transformed the lives of many of the composers themselves. He was also recognised internationally as the supreme authority on the life and music of Kurt Weill.

David Drew was born in Putney in 1930 and had a taste of travel before his first birthday: four months in Berlin, where his father was working. His parents divorced around his second birthday, and with the marriage of his mother to a Campbeltown solicitor, he moved to Scotland. Education gradually brought him south again: he attended school in Aysgarth in Yorkshire (1938–43), where in 1939 he had his first piano lessons, and Harrow (1944–49), where, to Drew's delight, a disagreement with his piano teacher brought a replacement in the form of Ronald Smith, later known for his championship of Alkan.

While at Harrow Drew also took up the oboe and tried his hand at composition, mostly song-settings, where his choice of poets – Carl Sandburg, Logan Pearsall Smith, Adelaide Crapsey, Edward Thomas – indicated the intellectual curiosity that was later to characterise his writing. In March 1947 the first UK performance of Stravinsky's Symphony in Three Movements, conducted by Ernest Ansermet and broadcast by the BBC, proved a revelation. The direction of his life was being set.

He entered the embrace of National Service in 1949–50 before attending Peterhouse College in Cambridge (1951–53) for a degree in History and English, where his regular contacts with the exiled Catalan composer Roberto Gerhard foreshadowed the huge international network of composers he soon began to build up.

Graduating in May 1953, Drew began six years as a freelance critic and writer, producing sleeve-notes for Decca and EMI, contributing articles to The Score (including the first major article on Messiaen in any language), The Musical Times and Music & Letters, as well as much music journalism in the non-specialist press. He also became a frequent broadcaster, not least on Julian Herbage's and Anna Instone's Sunday morning BBC programme, Music Magazine. A 60-page essay on French music published in 1957 in 20th Century Music, a symposium edited by Howard Hartog, is still quoted 50 years later, a model of style and lucidity.

Drew was by now a familiar figure at modern-music festivals on mainland Europe, at Darmstadt, Baden Baden, Venice and elsewhere. It was at the Berlin Festival in 1957 that he met Kurt Weill's widow, Lotte Lenya, having decided the previous year that Weill's music – then largely known only because of his collaborations with Brecht – merited a full-length study.

Weill was to become the leitmotif that ran through his life. He soon commissioned – by the composer Boris Blacher, for the West Berlin Academy of Arts – to catalogue the manuscripts in the house in upstate New York where Weill lived until his death in 1950. In the years to come Drew produced a collection of Weill's own writings and an anthology of contemporary comment on him, both published in German in 1975, and Kurt Weill: A Handbook (Faber, 1987), an exhaustive catalogue raisonné. But though the long-awaited critical biography occupied Drew for half a century, it was never published. A three-volume life-and-works was nearly complete when it was discontinued in 1976; it remains to be seen whether his papers contain a recasting of the material.

March 1959 saw Drew appointed music-critic of The New Statesman and Nation, a post he held for eight years. In 1960 a brief dalliance with the BBC Music Department – then under the sway of William Glock, an ardent propagandist for new music – proved incompatible with his existing commitments and he turned down a full-time job there. But through Glock he became the head of a landmark contemporary-music recording project funded by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

Drew was now internationally regarded not only as an authority on Weill but as a leading figure in contemporary music in general. He was consulted for stage presentations, festivals and concert series, and was a valued presence on a number of committees, among them the BBC Central Music Advisory Committee, the Music Panel of the Arts Council of Great Britain and its Contemporary Music Network, and the British section of International Society for Contemporary Music. An important development in his life came in spring 1971, with his appointment to the editorship of Tempo, the modern-music quarterly published by Boosey & Hawkes. He immediately stamped his authority on the publication, commissioning 17 prominent composers to write short pieces in memory of Stravinsky, who died just after Drew took up the reins.

The relationship with Boosey & Hawkes was soon to deepen. Tony Fell, named Managing Director in 1974, was appalled to find no strategy for publishing new music and no one responsible; it was, he said, "like running an atomic power station without any physicists". The composer Nicholas Maw recommended Drew, and Fell had found his physicist.

The 17 years Drew was to spend at Boosey & Hawkes, from 1975 to 1992, first as Director of Publications and then Director of New Music, transformed the company. He proved an irresistible recruiting sergeant as, with Fell, he pulled in major composers by the armful. Helen Wallace's recent Boosey & Hawkes: The Publishing Story lists the figures they conscripted: John Adams, Elliott Carter, Berthold Goldschmidt, Henryk Górecki, H.K. Gruber, Robin Holloway, James MacMillan, Steve Reich, Kurt Schwertsik, Michael Torke and York Höller; B&H also represented the entire catalogue of Igor Markevitch and major works of Leonard Bernstein and Roberto Gerhard.

The external success concealed internal frictions. Drew could be almost dauntingly intense: he seemed to tackle life with the furious passion of a hunting shrew, and in conversation you could sometimes sense that his mind was working on several other issues simultaneously. A maverick individualist with his own convictions is always going to sit ill in a corporate structure, and so it proved with Drew at Boosey. His departure resolved tensions on both sides; the miracle is that the relationship lasted so long.

Contact with Drew was energising: after a talk with him you felt you should be doing much more. The American writer Bernard Jacobson, then based in London, found that working with David for five years, first as his deputy, and then alongside him as Director of Promotion, was a stimulation, an education, and an almost unalloyed pleasure. You didn't think lazily around David. He had a mind of Byzantine complexity and unabating originality, and he wrote superbly.

For all his intensity, Drew could be thoughtful and generous in unassuming ways: I can't be the only writer to have received little notes from him (often only one word: "Congratulations" or "Bravo") in response to an article he had enjoyed, usually in Tempo, and long after he had handed the reins over to Malcolm MacDonald, formally in 1974 and finally in 1980. He was withal a deeply private man, devoted to his family.

Freelance once again in 1992, he plunged once more into writing, consultancy (producing a series of CDs for Largo Records) and editing, not least further Weill scores – all activities he was eventually to document in fascinating detail in an autobiographical outline on his website (www.sing- script.plus.com/daviddrewmusic). He kept adding to his huge tally of articles, which covered not only the composers he had promoted at Boosey & Hawkes but also other major figures, such as Boris Blacher, Luigi Dallapiccola and Roger Sessions and as well as less-well-known ones, like Christopher Shaw and Leopold Spinner; he recently contributed a major article on Walter Leigh, a Hindemith student killed near Tobruk in 1942, to a festschrift organised by the Hindemith Institute.

Nicholas Kenyon, former controller of the Proms and now Managing Director of the Barbican Centre, wonders whether Drew's perfectionism proved a hindrance: "David was the most prodigiously knowledgeable and the most intellectually generous writer on music: I learnt a huge amount from him. There was one thing that somehow frustrated his fully expressing all this, and that was his constant struggle to get it all precisely right, to include every sublety. We all wish he had written more."

The Leigh essay, indeed, was intended to form the basis of a monograph on this neglected figure, and becomes one of the numerous projects that David Drew's death leaves unfinished. Although he was almost 80, his mind was still working as fiercely as ever.

Martin Anderson

David Drew, writer, musicologist, editor and publisher; born 19 September 1930; married 1960 Judy Sutherland (one son, two daughters); died 25 July 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks