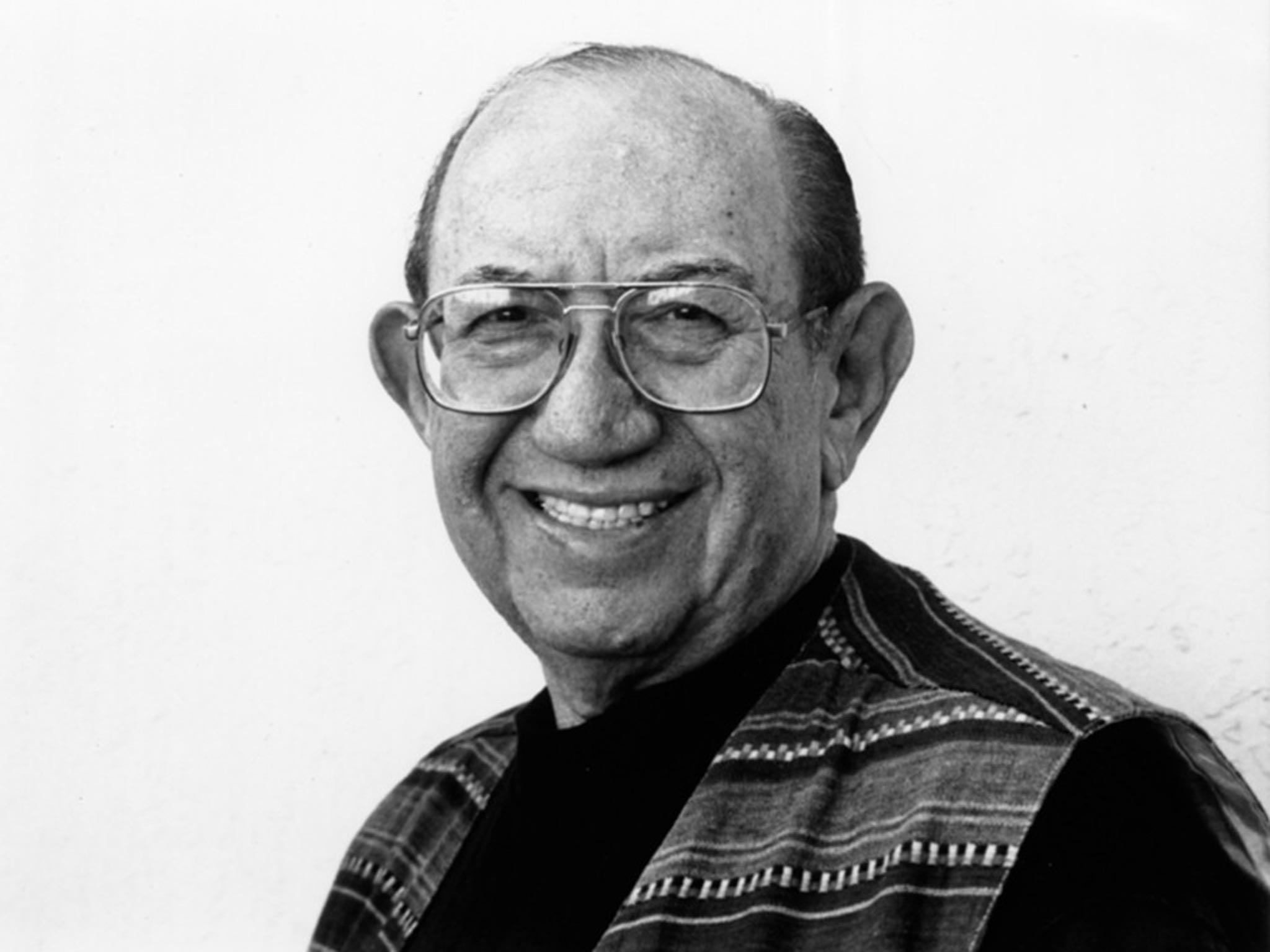

Daniel Keyes: Author whose science fiction story 'Flowers for Algernon' became a bestselling novel and an Oscar-winning film

Daniel Keyes was the author of the classic novel Flowers for Algernon, an account of a mouse and a man whose IQs are artificially, temporarily and tragically increased. First published in 1959 as a short story, it was released in novel form in 1966 and has sold millions of copies. Generations of English students have met Charlie Gordon, the book's narrator, through the journal entries that Daniel Keyes crafted in stunted, then elegant and then again stunted prose revealing his character's transformation.

Millions more saw Charly, Ralph Nelson's 1968 film adaptation starring Cliff Robertson in an Academy Award-winning performance, or watched the television films and musical based on the novel. Keyes explored the human mind in several other volumes but Flowers for Algernon remained his defining work.

When the book opens, Charlie is 32 and holds a menial job in a bakery. He is severely intellectually disabled but learns that he may be a candidate for an experimental surgery to increase his intelligence. "Dr Strauss says I shoud rite down what I think and remembir and evrey thing that happins to me from now on," Charlie recounts in his first "progris riport." "I dont no why but he says its importint so they will see if they can use me... I want to be smart."

The surgery had been successfully conducted on a mouse named Algernon who manages to navigate mazes with dazzling speed. Charlie finds similar success, but not happiness, after his surgery. "This intelligence has driven a wedge between me and all the people I knew and loved, driven me out of the bakery," he writes. "Now, I'm more alone than ever before. I wonder what would happen if they put Algernon back in the big cage with some of the other mice. Would they turn against him?" In time, Charlie realises that Algernon's new-found intelligence is fading, and that his will fade as well.

Keyes received the Hugo Award for his original short story and the Nebula Award for his novel, both in recognition for achievements in science fiction or fantasy. To many readers, the work transcends the genre. The story was widely praised, including by Isaac Asimov.

"Here was a story which struck me so forcefully that I was actually lost in admiration ... for the delicacy of his feeling, for the skill with which he handled the remarkable tour de force involved in his telling the story," Asimov observed in Paratexts: Introductions to Science Fiction and Fantasy. "How did he do it?" Keyes said the story came from episodes in his own life, all preserved in what he described as the cellar of his mind.

Keyes, the son of Ukrainian immigrants, was born in 1927 in Brooklyn. In his 1999 memoir, Algernon, Charlie, and I: A Writer's Journey, Keyes wrote that his parents had wanted him to become a doctor. He was waiting for a train to a university class, he recalled, when he was struck by two thoughts: "My education is driving a wedge between me and the people I love." And then: "What would happen if it were possible to increase a person's intelligence?" Later, he wrote, he was disturbed when he took part in the dissection of a white mouse.

Keyes changed fields of study. He served in the US Maritime Service before receiving a bachelor's degree in psychology in 1950 from Brooklyn College, where he also received a master's degree in American literature in 1961. He taught in the early years of his career in New York schools and was later a professor at Wayne State University in Detroit and at Ohio University. He said he never forgot an encounter with a pupil in a class for the developmentally disabled. "Mr Keyes, this is a dummy class," he recalled the student saying. "If I try hard and get smart before the end of the term, would you put me in a regular class? I want to be smart."

In another class, Keyes said that he witnessed the dramatic progress of a student with learning difficulties who then regressed when he was removed from lessons. "When he came back to school, he had lost it all," Keyes said. "He could not read. He reverted to what he had been. It was a heartbreaker."

Keyes went on to write other novels, including The Touch (1968), about an industrial accident involving radioactive material. His non-fiction works included The Minds of Billy Milligan (1981) about an accused criminal who was said to have suffered from multiple personality disorder. "The challenge of first unearthing this story ... and then telling it intelligibly was a daunting one," wrote the critic Joseph McLellan. "He has carried it off brilliantly, bringing to the assignment not only a fine clarity but a special warmth, and empathy for the victim of circumstances and mental failings that made Flowers for Algernon one of the most memorable novels of the 1960s."

Keyes continued writing until his death, his family said. "I've learned that intelligence alone doesn't mean a damn thing," he once said. "It only leads to violence and pain."

EMILY LANGER

Daniel Keyes, author and teacher: born Brooklyn, New York 9 August 1927; married Aurea Vazquez (died 2013; two daughters); died Florida 15 June 2014.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks