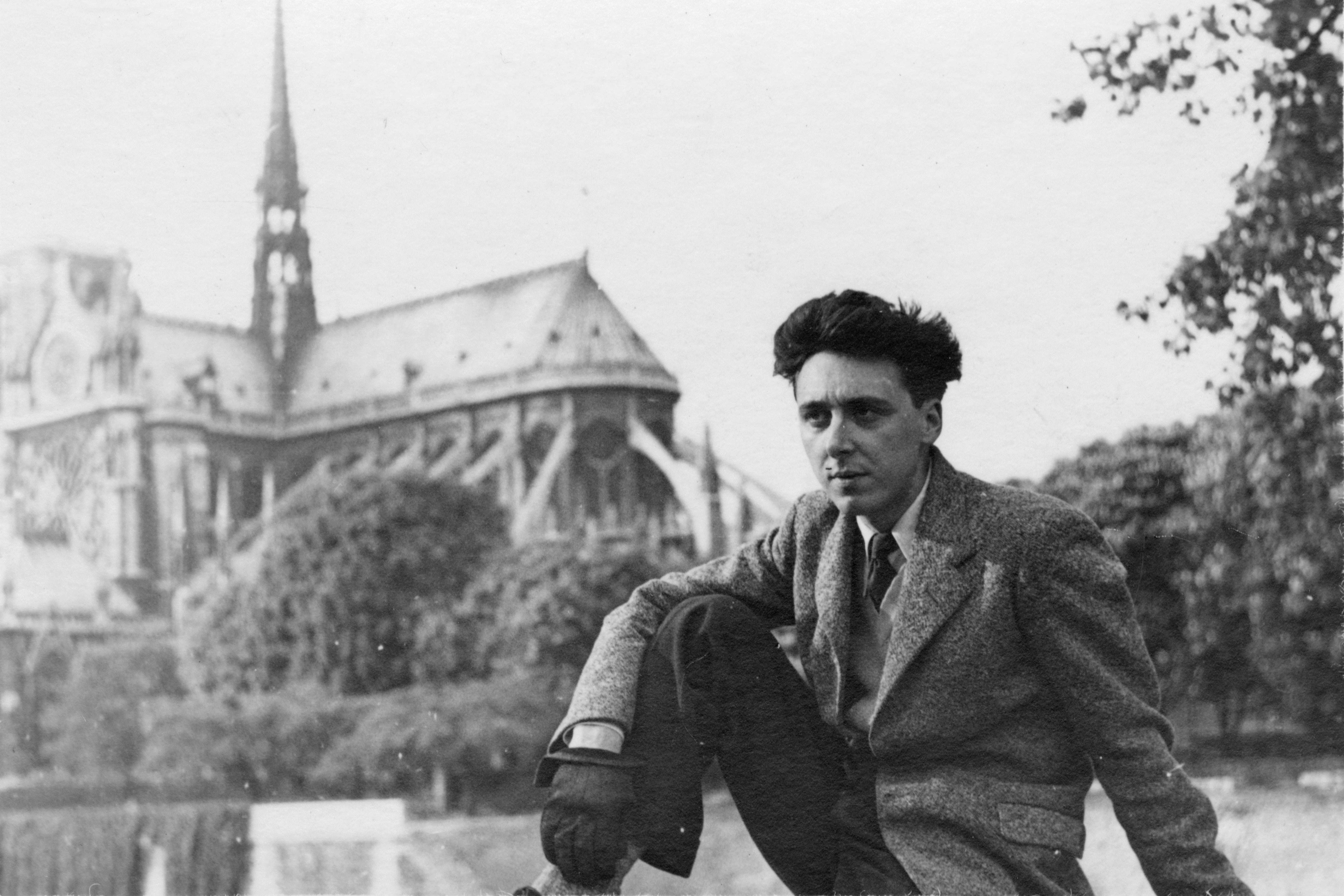

Daniel Cordier: One of the last heroes of the French resistance

Later becoming an art gallery owner, he helped to coordinate and unify the disparate guerrilla groups who set out to attack, confuse and distract the Nazis

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Aged 19 and about to join the French army to fight the Nazi invaders, Daniel Cordier heard on the radio in June 1940 that France’s military head of state, Marshal Philippe Pétain, had capitulated to the Germans.

“I naively thought, as my parents did, that Pétain was going to launch France’s victorious counteroffensive,” Cordier recalled in a 2010 interview with the public radio channel France Culture. “Instead, he announced the end of the fighting, that is to say the end of hope. I burst into tears, went up to my room and sobbed.”

Then, mustering a choice epithet about Pétain, he regrouped. Cordier became a key member of the French resistance, helping coordinate and unify the disparate guerrilla groups who set out to attack Nazi trains and bases to weaken, confuse and distract them in the run-up to the 1944 Allied landings at Normandy. After the war, he became a leading modern art gallery owner in Paris as well as a prolific author on his wartime experiences.

Cordier died on 20 November at 100 at his home near Cannes, according to a statement by French president Emmanuel Macron. In 2018, Macron awarded Cordier the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour, the highest level of that prestigious national order.

In addition to 100-year-old Hubert Germain, Cordier was the last surviving resistance fighter of the 1,038 – including six women – honoured by resistance leader Charles de Gaulle at the end of the Second World War with the title Companion of the Liberation.

Cordier was best-known as the personal secretary and right-hand man of legendary resistance leader Jean Moulin, who had served as first president of the National Council of the Resistance. In that role, Moulin pulled together French patriots from all walks of life – and from far right to communist – to disrupt the Nazis and support the Allies before, during and after the D-Day invasion on 6 June 1944.

Based in the city of Lyon, Moulin was the senior on-the-ground resistance member appointed by De Gaulle from his exile headquarters in London. Although he carried a pistol and dagger while on the streets, Cordier’s main task was to code and decode radio messages between London and Lyon, some of them via the BBC World Service.

Daniel Bouyjou was born in Bordeaux on 10 August 1920, to a conservative, bourgeois businessman. He was four when his parents divorced, and two years later he adopted the surname Cordier from his stepfather.

Influenced by his stepfather, young Daniel took to absorbing the works of French writer and political theorist Charles Maurras, an extreme right-wing nationalist, royalist and open antisemite who became an early political hero to him. At the same time, he was drawn to the work of future Nobel laureate André Gide, who rebelled against bourgeois conventions and wrote of sensual fulfilment.

While attending a series of Catholic boarding schools, he later wrote of his attraction to other boy pupils. But in describing among his peers a “hatred” and intolerance toward gay people, he waited until age 89 to come out, around the time he published an award-winning memoir, Alias Caracalla.

Days after Pétain’s June 1940 “armistice” with the Nazis, Cordier and 15 patriotic friends boarded a Belgian cargo ship ostensibly bound for French Algeria. In fact, it changed course, and they landed on 25 June at Falmouth, England, before heading for London to join the fledgling Free French Forces led by De Gaulle. Brought up as a conservative Catholic, his first shock was to find that many of his new comrades were socialists or communists.

After guerrilla training, he was assigned to the Free French Intelligence and Operations Bureau. Intending to, as he wrote in his memoir, “tuer du Boche” (slang for “kill Germans”), he parachuted into France on 25 July 1942, from an RAF plane, hitting the ground at Montluçon. He had to find his way to Lyon, 170 miles away, and link up with a resistance leader De Gaulle had named only as Rex.

Cordier, whose code name was Bip W, became Rex’s right-hand man until the latter was captured by the Gestapo in June 1943 and tortured to death within days, reportedly at the hands of local Gestapo chief Klaus Barbie, known as “the Butcher of Lyon”. It was more than a year before Cordier learnt that Rex’s real name was Jean Moulin.

In his memoir, Cordier recalled a clandestine visit to Paris during the Nazi occupation. He was appalled to see German soldiers posing for each other’s photographs in front of the city’s Arc de Triomphe. Even worse was the sight of an elderly man and a child wearing overcoats with a yellow star marking them as Jews. His antisemitism had long since evaporated during the resistance, which included many Jews.

Warned that the Gestapo was after him, Cordier fled to Spain in March 1944 across the Pyrenees but was arrested by the forces of General Franco and interned at camps first in Pamplona and later at Miranda de Ebro. Released after two months, he reached London and continued the resistance there as an intelligence agent liaising by radio with guerrillas back in France.

During his time with Moulin, who had a background in art collecting, Cordier developed a similar expertise for their cover as dealers. After the war, he began collecting and opened what became a successful modern art gallery in Paris. “A work of art is not to ease but to awaken and hassle the mind,” he once said. He later donated much of his collection to France’s National Museum of Modern Art, which he had helped found.

In his later years, he dedicated his life to writing about Moulin. He bought a camper van and toured places where his old boss had worked in French civil administration before the war, gathering documents, letters and manuscripts along the way. He published well-received volumes on Moulin.

In the 1960s, Cordier adopted an orphaned teenager, Hervé Vilard, who had moved among foster homes after living on the streets of Paris. Hervé, who became a pop singer in France and is now 74, survives him.

Daniel Cordier, French resistance fighter, born 10 August 1920, died 20 November 2020

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments