Cory Aquino: President of the Philippines who brought democracy to the islands

When Cory Aquino stepped down after six years as the first woman president of the Philippines, she was widely viewed as having made little impact on her country's deep-rooted social and economic problems.

The moment of her departure from the presidency was a low point in her brief yet quite remarkable political career, leaving as she did in an atmosphere of disenchantment and unrealised hopes. Yet overall, she left a mark on the history of her troubled country, so deep and so lasting that her death will bring a surge of emotion as the heady days of the short but memorable Aquino era are reassessed.

As president of the Republic of the Philippines between 1986 and 1992, she led her country's eventful transition from dictatorship to democracy. In a few turbulent years, she gained a presidency which she had not wanted, and which came to her at the cost of the death of her husband. She was thrust into power by his assassination and by the passion of the millions who took to the streets to sweep away the regime of Ferdinand Marcos.

But in office, she could not bring the Philippines' military fully under control: a number of coups were launched against her, and indeed she was succeeded by a general. But the Philippines never returned to the type of dictatorship she displaced, and she won worldwide acclaim for her commitment to democracy.

Maria Corazon Cojuangco Aquino, popularly called Cory, was born in 1933 into a wealthy family which had for generations been immersed in politics. Most of her education took place in the US, where she took a degree in French and mathematics in New York.

Returning to the Philippines, she married Benigno Aquino, known as Ninoy, who also came from a wealthy political family. At that point, she abandoned her legal studies in order to become, in her words, "just a housewife". She raised five children while her husband spent his career opposing the regime of Marcos, an ex-soldier whose brutality and cunning kept him in power for two decades.

It was during his time ruling this poverty-stricken country that Marcos's wife, Imelda, famously, or infamously, amassed more than 2,000 pairs of shoes in what was seen as a monument to vanity and excess.

When Marcos introduced martial law in 1972, Ninoy and others were thrown in prison on trumped-up charges. In the seven years her husband spent in jail, Aquino came to the forefront, campaigning against his imprisonment.

She acted as his link to the outside world as he kept up his agitation from his prison cell, running for election and at one stage going on hunger strike.

She said of her role: "I am not a hero. As a housewife, I stood by my husband and never questioned his decision to stand alone against an arrogant dictatorship. I never missed a chance to be with my husband when his jailers permitted it. I never chided him for the troubles he brought on my family and their businesses."

When Ninoy was diagnosed with a heart complaint, Marcos allowed the family to travel to the US so that Ninoy could have triple-bypass surgery. After successful surgery, they remained in America, Ninoy taking an academic post at Harvard.

After three years, however, he was persuaded by supporters to return to the Philippines to help lead the opposition. Everyone knew his life was in danger, but few realised that assassins would strike so quickly. Just minutes after his plane landed at the heavily guarded Manila International Airport in August 1983, he was shot dead on the tarmac. Marcos protested his innocence of involvement in the incident, but few believed him.

Uproar followed. Marcos, in ordering such a flagrant killing, showed he had lost much of the guile which had kept him in power. The huge attendance at Ninoy's funeral, and the waves of protests that followed, indicated that his days were numbered.

The shooting removed an opponent of the Marcos regime but created another, even more potent symbol, when Aquino returned to the Philippines and was drawn into political activity. "I know my limitations and I don't like politics," she said. "I was only involved because of my husband."

Marcos, seeing his power slipping away, called a presidential election in 1985 in the hope of shoring up his authority. Anti-Marcos factions were fragmented, but most eventually accepted that Aquino stood the best chance of providing unity. She hesitated, spending 10 hours in meditation at a convent near Manila before deciding to run.

She was to explain later: "We had to present somebody who was the complete opposite of Marcos, someone who has been a victim. Looking around, I may not have been the worst victim, but I was the best-known."

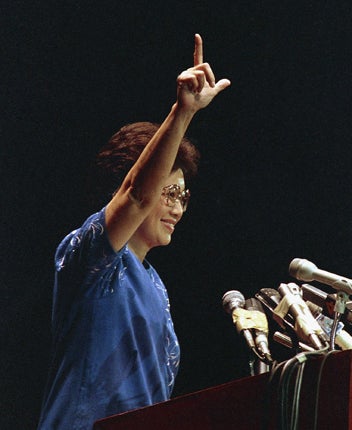

During the campaign, she conveyed the simple but potent message that the time had come for democracy. She was, in her trademark plain-yellow dresses, an ostensibly insignificant figure, but she was a powerful human reminder of Marcos's use of violence.

In the election, Marcos, resorting to vote-rigging, declared himself the victor before all votes were counted. The move was so brazen that it provoked an uprising in which millions took to the streets. At this point, many of the major power elements concluded that Marcos's time was over. Aquino had support from sources such as the Catholic church, while some important army officers abandoned Marcos and aligned themselves with her.

Washington, too, dropped Marcos. Ronald Reagan had followed previous administrations in regarding Marcos as a "Pacific strongman" who provided a useful bulwark against communism. In doing so, the US had tended to ignore his regime's corruption and breaches of human rights.

But the Ninoy assassination and the election-fixing lost him the sponsorship of Washington, though the US did supply helicopters to whisk Marcos and Imelda into exile (most of her shoes were left behind).

"We are finally free," Aquino declared at the time. "The long agony is over." She was fêted around the world, Time magazine saying of her: "She managed to lead a revolt and rule a republic without ever relinquishing her calm or her gift for making politics and humanity companionable. In a nation dominated for decades by a militant brand of macho politics, she conquered with tranquillity and grace."

But in the years of her presidency, little went right for her as moral strength failed to translate into the sufficient political acumen to tackle the huge problems of the Philippines. Her husband had, in fact, predicted that whoever succeeded Marcos was doomed to fail. He would not for a moment, however, have thought that the successor would be his wife, whose administration was overwhelmed by massive economic difficulties. These included grinding poverty and the legacy of two decades of totalitarian rule. An earthquake and an erupting volcano added to her woes.

She had herself referred to her country as "the basket case of South-East Asia". But while Marcos had been firm – to the point of brutality – her government was thought of as hesitant and indecisive.

One area in which she did display firmness, however, was in her relations with the army: she had little choice, since various elements launched no fewer than seven coup attempts against her in three years. With the help of generals who remained loyal to her, she faced down all of these: the irony was that a woman who came to power on a platform of peace should have to devote so much effort to fending off recurring violent challenges.

But she was cool under fire, and she indignantly sued when a journalist claimed she had taken refuge under a bed during one attack.

Her personal chief of security, Colonel Voltaire Gazmin, recently testified that she was steady under pressure. "I vividly remember the coup attempt of August 1987," he wrote. "I was out supervising the placement of armour around the palace when bursts of gunfire rang out. I rushed to the official residence and found the president and her family upstairs. I asked them to go downstairs and turn off all the lights, and instructed my guards to stand mattresses against the windows.

"I then made a head count and found one missing. I went back upstairs and noticed light coming through the open bathroom door. It was the president combing her hair."

The colonel said that when he begged her to leave, she replied that she needed to look "presidentially presentable". She was, he said, "the calmest soul around".

Although none of the coup attempts was successful, they eroded confidence in her administration. After so many unhappy economic and military experiences, she decided not to seek re-election and backed a loyal general, Fidel Ramos, who succeeded her as president. She was disappointed by her government's performance, but took consolation in the fact that the administration which succeeded hers was installed by a democratic vote.

She will thus be remembered both for the manner of her assuming office and for the manner of her vacating it.

Cory Aquino, former president of the Republic of the Philippines: born Paniqui, Philippines 25 January 1933; married 1954 Benigno Aquino (died 1983; one son, four daughters); died Makati City, Philippines 1 August 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks