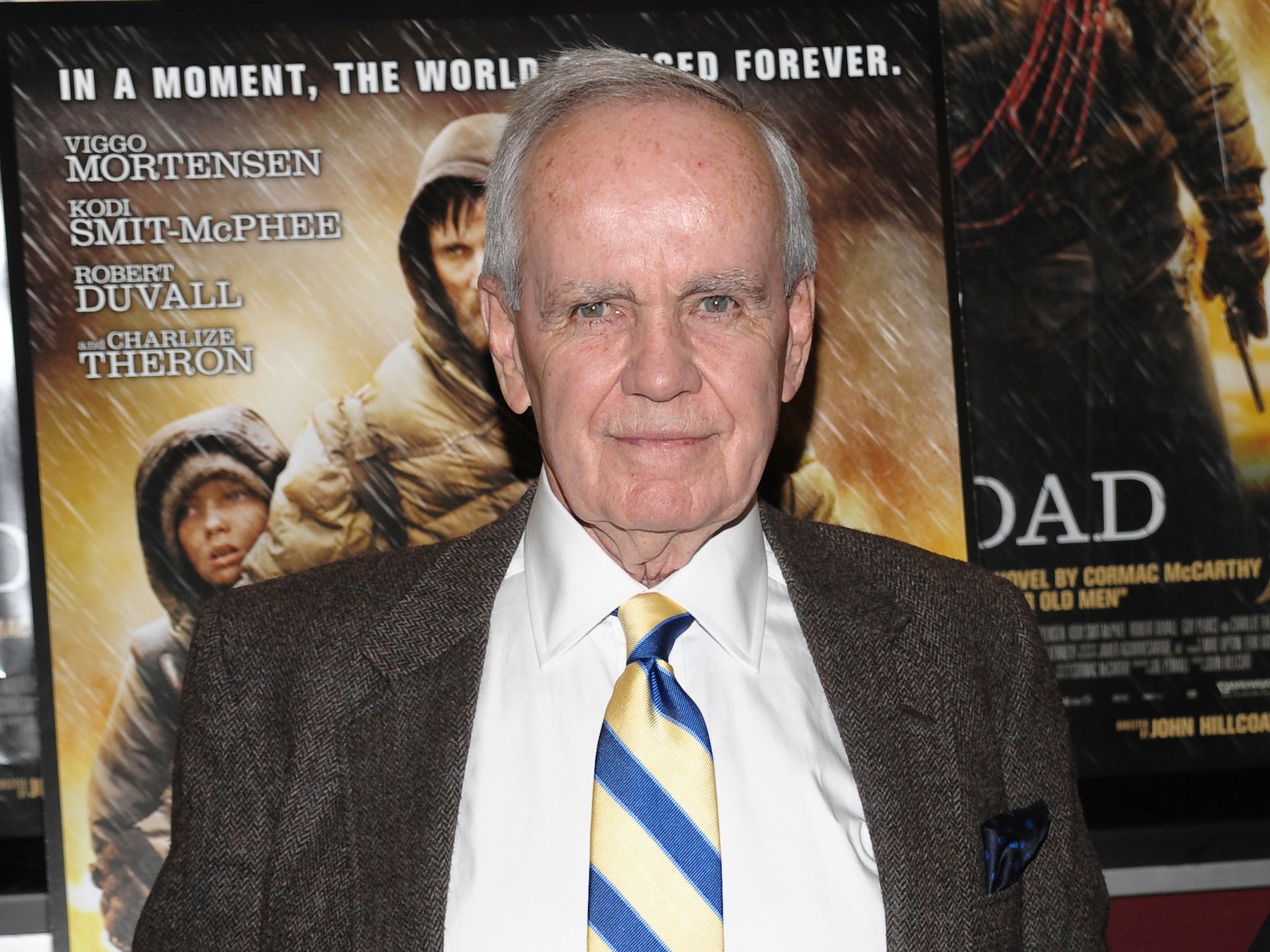

Cormac McCarthy: Haunting novelist who lived to tackle life’s dark side

His idiosyncratic prose style drew comparisons with Joyce and Shakespeare but while a fierce devotion to his craft turned the ‘writer’s writer’ into a Pulitzer Prize-winner, it also took its toll on those closest to him

Cormac McCarthy, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author whose lyrical and often brutally violent novels propelled him to the first ranks of American fiction, immersing readers in scenes of savagery, despair and occasional tenderness in the backwoods of Tennessee, the deserts of the southwest and the ashen desolation of a post-apocalyptic world, has died aged 89.

McCarthy explored the dark side of human nature in a dozen novels that were lean and poetic, poignant yet unsentimental. “If it doesn’t concern life and death,” McCarthy once told Rolling Stone, “it’s not interesting.”

For the first quarter-century of his career, McCarthy was little more than a cult figure, a “writer’s writer” who declined to talk to most reporters and was rumoured to live like a hermit.

None of his first five books sold more than 3,000 hardcover copies, and even glowing reviews of his novels emphasised that they were not exactly a pleasure to read: his semi-autobiographical novel Suttree (1979) was likened to “a good, long scream in the ear,” while his western epic Blood Meridian (1985) was said to hit readers “like a slap in a face”. The novel has a scene in which dead babies are found hanging from a tree.

McCarthy’s prose style was strikingly idiosyncratic, earning comparisons to James Joyce, Shakespeare and the King James Bible. He stripped most of his sentences of punctuation, limiting his use of commas and dispensing with semicolons and quotation marks altogether; played with traditional syntax; and sprinkled his novels with obscure words (vermiculate, gryke, patterans, rachitic), while using naturalistic dialogue to anchor his books in time and place. “This whole thing is just hell in spectacles,” says one of his lawman characters.

As McCarthy played with conventions of the western, crime thriller and horror genres, reviewers found that his writing became slightly more accessible over the years. He received the National Book Award and National Book Critics Circle Award for All the Pretty Horses (1992), one of his most romantic westerns, and the Pulitzer Prize for The Road (2006), about a father and son trudging across the United States in the wake of an unspecified disaster.

In 2009, he followed Philip Roth in becoming the second author to receive the PEN/Saul Bellow Award for lifetime achievement in American fiction.

“His writing is a hypnosis of detail. He makes you feel that, because this place is palpably real, these events would seem to be true,” New York Times book critic Anatole Broyard wrote in a review of Suttree, about a man who abandons a life of privilege in the 1950s to live on a houseboat in Knoxville, on the Tennessee River.

McCarthy received some of the best reviews of his career for Blood Meridian, perhaps his most violent book, which literary critic Harold Bloom called “the ultimate western, not to be surpassed”.

Loosely based on historical events, it followed a 14-year-old known simply as “the kid,” who joins a group of scalp-hunting bounty hunters after the Mexican-American War. The gang’s members include a hairless, 7ft-tall giant named Judge Holden, who kills without hesitation, dances and fiddles with seemingly boundless energy, and declares that “war is god,” emerging as a monster in the mould of Shakespeare’s Iago.

McCarthy used campfire exchanges between the judge and the kid to examine ideas about war, fate, religion and the collapse of civilisation. He also demonstrated his literary range by mixing short, punchy lines with sentences that sprawled across the page

The author declined all but a handful of interview requests – even when he appeared on TV, interviewed by Oprah Winfrey after she selected The Road for her book club, he was almost inert – and preferred to steer the conversation away from literature, talking about country music, theoretical physics or the behaviour of rattlesnakes.

Despite the rumours, he was hardly a recluse. He frequented El Paso pool halls, befriended the high-stakes poker player Betty Carey and was a longtime fixture of the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico, a scientific research centre that was co-founded by his friend Murray Gell-Mann, a Nobel-winning physicist.

McCarthy refused to teach creative writing, calling it “a hustle”, and never went on tour or gave public readings. When it came to autographing books, he told The Wall Street Journal that he signed 250 copies of The Road and gave them all to his younger son John, “so when he turns 18 he can sell them and go to Las Vegas or whatever.”

His apparent lack of interest in promoting his novels was complemented by a fierce devotion to writing them, sometimes at the expense of his family life. His three marriages ended in divorce, and he described himself as an absent father to his first son, who was born while he was working on his debut novel.

“Anything that doesn’t take years of your life and drive you to suicide hardly seems worth doing,” he told the Journal in 2009, explaining why he wrote novels rather than short stories. He added: “Creative work is often driven by pain. It may be that if you don’t have something in the back of your head driving you nuts, you may not do anything. It’s not a good arrangement. If I were God, I wouldn’t have done it that way.”

The third of six children, Charles Joseph McCarthy Jr was born in Providence, Rhode Island, on 10 July 1933. McCarthy – by some accounts, Cormac was an old family nickname – grew up in Knoxville, where his father worked for the Tennessee Valley Authority and became the federal power utility’s top lawyer.

From a young age, he rebelled against his upper-middle-class upbringing. “I was not what they had in mind,” he said of his parents. “I felt early on I wasn’t going to be a respectable citizen. I hated school from the day I set foot in it.”

McCarthy graduated from parochial school, enrolled at the University of Tennessee, dropped out and joined the air force. While stationed in Alaska, he began reading obsessively, drawn to the novels of Melville, Dostoevsky and Faulkner. He returned to the University of Tennessee in 1957 and dropped out again three years later to focus on writing what became his first novel, The Orchard Keeper (1965).

By the time The Orchard Keeper was published, McCarthy was married and divorced from his first wife, poet Lee Holleman McCarthy, with whom he had a son, Cullen.

Decades later, her obituary in the Bakersfield Californian said that she filed for divorce when McCarthy asked her to “get a day job so he could focus on his novel writing,” even though she was already “caring for the baby and tending to the chores of the house”.

The abandonment of a child kicked off the plot of McCarthy’s second novel, Outer Dark, which he wrote while living on the Spanish island of Ibiza with his second wife, Anne De Lisle, a British singer. They met while he was travelling to Europe on an American Academy of Arts and Letters fellowship, and they later moved near Knoxville, where McCarthy gradually converted an old dairy barn into a home.

“We lived in total poverty,” De Lisle told The New York Times. “We were bathing in the lake. Someone would call up and offer him $2,000 to come speak at a university about his books. And he would tell them that everything he had to say was there on the page. So we would eat beans for another week.”

They separated in 1976, around the time McCarthy moved to El Paso, fascinated by the landscape and mythology of the West.

Although McCarthy maintained a reputation as an unusually single-minded author, plugging away at his novels without a care for their commercial prospects, he also wrote for film and television, penning the screenplay for Ridley Scott’s crime thriller The Counselor (2013). One of his unsold screenplays inspired the Border Trilogy; another evolved into No Country for Old Men, about the aftermath of a drug deal gone wrong.

McCarthy also wrote two plays, The Stonemason (first performed in 1995) and The Sunset Limited (2006), which he adapted into an HBO movie. The 2011 film starred Samuel L Jackson as Black, an ex-convict and born-again Christian who tries to dissuade White (Tommy Lee Jones, who also directed) from suicide.

In addition to his two sons, McCarthy is survived by a brother; two sisters; and two grandchildren.

By the early Noughties, McCarthy was spending much of his time at the Santa Fe Institute, where he served as a kind of artist-in-residence, chatting with researchers and helping edit their work for publication. He found scientists far more interesting than writers, he said, and drew on his time there to write what was apparently his first nonfiction piece, a 2017 essay for the science magazine Nautilus, in which he examined the relationship between language and the unconscious.

His scientific interests seeped into his last two books, The Passenger and Stella Maris, intertwined novels that were published within weeks of each other in 2022. The books focused on two siblings, a math prodigy and her salvage-diver brother, with an incestuous attachment and a father who helped develop the atomic bomb.

McCarthy declined to talk about the books after they were published, but he was known to have been working on the novels for more than a decade, fuelled by a recognition of his advanced age.

“Your future gets shorter and you recognise that,” he said in 2009. “In recent years, I have had no desire to do anything but work and be with John. I hear people talking about going on a vacation or something and I think, what is that about? I have no desire to go on a trip. My perfect day is sitting in a room with some blank paper. That’s heaven. That’s gold and anything else is just a waste of time.”

Cormac McCarthy, author, born 20 July 1933, died 13 June 2023

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks