Coco Schumann: Jazz musician who defied Nazis and played his way through the horrors of the Holocaust

He married a woman who had watched him play as a member of the The Ghetto Swingers in the Theresienstadt concentration camp

“The music saved our lives,” said Coco Schumann of the songs he credited with keeping him alive through the Holocaust.

The jazz musician was born Heinz Jakob Schumann in Weimar Berlin. His father Alfred was a Christian German who converted to Judaism in order to marry his mother, Hedwig, who was Jewish by birth.

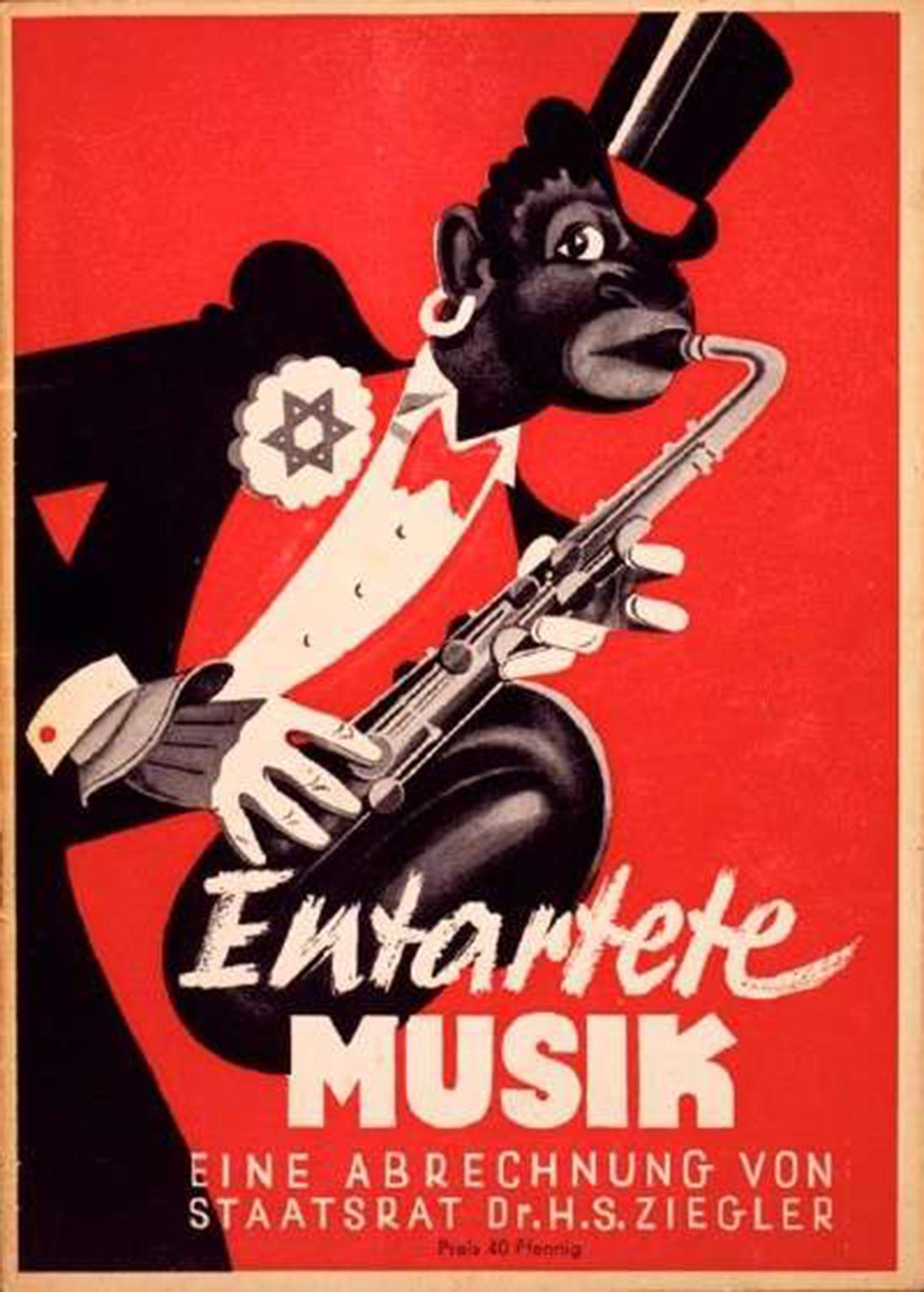

Schumann first fell in love with jazz at the age of 12. He was given a guitar at 14 and for a while he was taught how to play by a German teacher at school. However the Nuremberg Laws of 1938 made it illegal for Jews to learn music.

Schumann was not to be put off however. He refused to bow to the Third Reich. He continued to play whatever he liked and he would not wear a yellow star, saying of his refusal that “anyone who has swing in his blood ... cannot march in lockstep.”

Schumann’s luck held through the early years of the war. He dodged the attentions of the Reichmusikkammer, who regularly raided clubs to check that only approved German music was being played. When they got news of an imminent raid, Schumann and his fellow band-members would quickly switch from playing jazz to a German tune. He once recalled, “We had taken all precautions, too. We had torn off the Αmerican titles of the songs. Those were not musicians, they were Nazis, they could not read notes. So we simply pretended we had German songs in front of us.”

In 1942, Schumann got even more daring. When SS officers stormed a club he was playing, a Jewish member of the audience tried to flee via the stage.

Schumann remembered, “I went up to the SS officer and said, 'If you're going to arrest him, you should probably arrest me, too. First, I'm Jewish. Second, I am underage. And third, I am playing jazz’.”

He got away with it again. But a year later, at the age of 19, Schumann was taken to Theresienstadt – the concentration camp in Czechoslovakia where thousands were held before being sent to their deaths elsewhere. There he became a member of The Ghetto Swingers, filling in for their drummer, who had been transported to Auschwitz just the day before. Within the walls of the misleadingly comfortable concentration camp, which even had a café, they played forbidden jazz for the German guards.

“We feigned a normal life,” Schumann said. “We tried to forget that there was an impenetrable fence all around.”

The Ghetto Swingers even appeared in Nazi propaganda films extolling the virtues of the camp but like the drummer he replaced, Schumann was also eventually taken from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz. Of the 16 Ghetto Swingers, only three would survive. Schumann avoided death when an Auschwitz guard, who recognised him from the Berlin jazz scene, allowed him to form a band forced to play music to soothe the SS Guards while they tattooed new arrivals.

Schumann survived Auschwitz and a death march to Dachau and discovered on liberation that his parents too had made it through the war. Alfred had managed to hide his beloved wife Hedwig from the Nazis after having declared her dead in a house fire.

Shortly after he was liberated, Schumann met his wife Gertraud, who had also been in Theresienstadt. She recognised him as the drummer of The Ghetto Swingers. Together, they had a son.

In the post-war years Schumann returned to composing and playing, experimenting with new electronic guitars. He played with Marlene Dietrich at the Titania Palast and also with Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald, cementing his reputation as German’s foremost swing guitarist. For a while he moved to Australia and was successful there too. But eventually Germany drew him back.

Still Schumann refused to let his time in the concentration camps define him. “I am a musician who was imprisoned in concentration camps”, he said, “not a concentration camp prisoner who plays music.” For a long time even his friends were unaware of the full truth of Schumann’s war.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that he was prepared to talk about his concentration camp experiences. His change of heart came after an encounter with some students in a Bavarian pub. When the drunken young Germans declared their belief that the Holocaust never happened, Schumann knew he had to speak up.

His 1997 autobiography, The Ghetto Swinger: A Berlin Jazz-Legend Remembers, co-authored with Michaela Haas, was a bestseller – in 2012 it was staged as a musical in Hamburg.

Towards the end of his, when a German newspaper reviewed his memoir under the headline, “The horrible life of a jazz legend” Haas had Schumann’s ear. “But that’s not true,” he told her. “No, my dear, I tell myself, looking at this bright planet, it was a wild and colourful ride, at times too long, but always too short, life has shown me its unbelievably mean and terribly beautiful face. But one thing it was and is certainly not: horrible.”

Coco Schumann, jazz musician and Holocaust survivor, born 14 May 1924, died 28 January 2018

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks