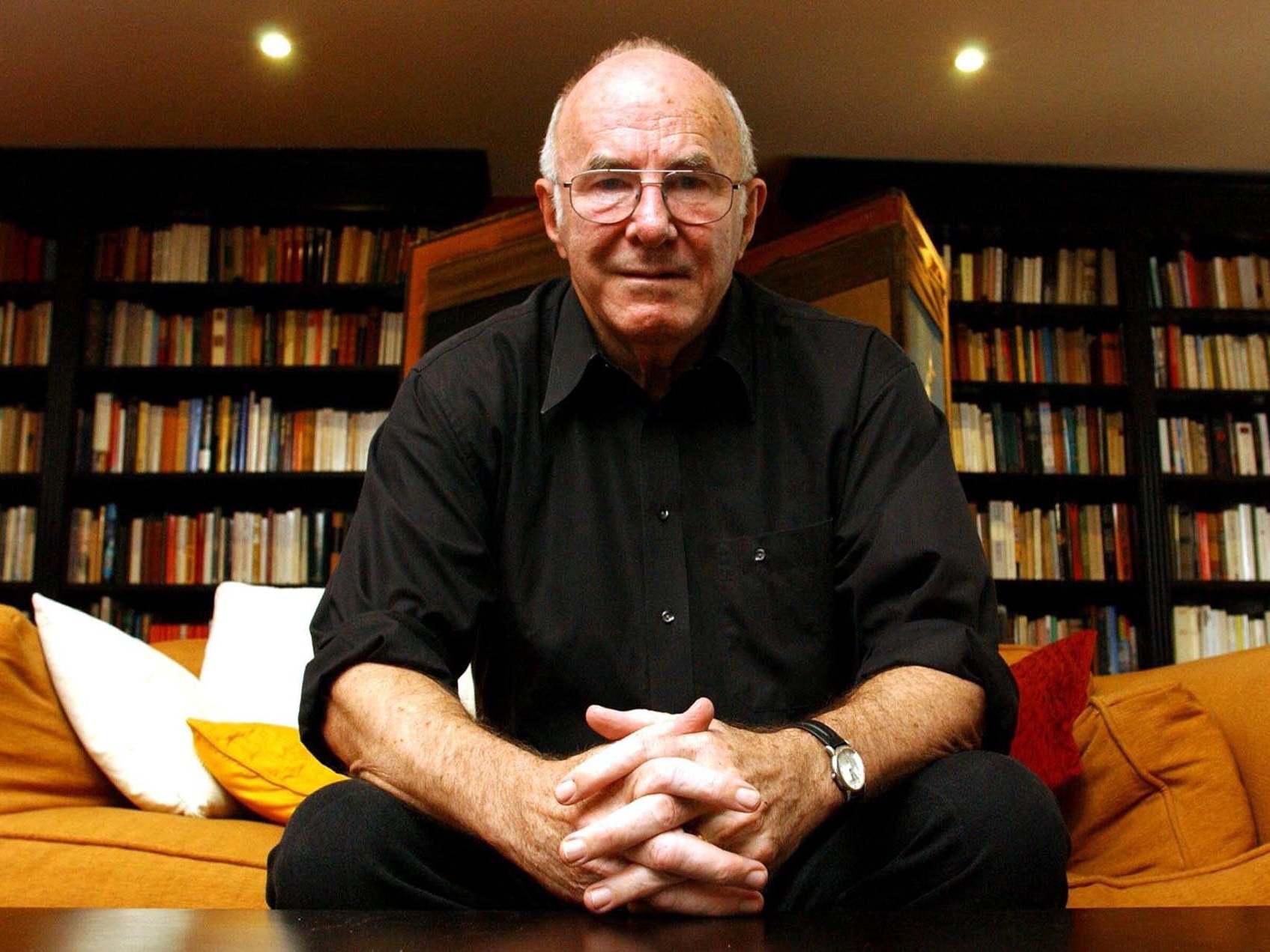

Clive James: Writer and broadcaster equally at home among the highbrow and on TV

A must-read critic and renowned wit, James was prolific in fiction, essays, poetry and autobiography

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Though sometimes described as “the wittiest man in England”, Clive James remained defiantly Australian through five decades of living in the UK. “Wit” (in the 18th century sense) was certainly his stock-in-trade, but his wasn’t the kind of wit designed to conceal intellectual depth: it paraded and exulted in that depth. His great gift was that he could use his often hilarious phrase-making skill across a vast range of media and that it appealed equally to popular and highly cultured audiences.

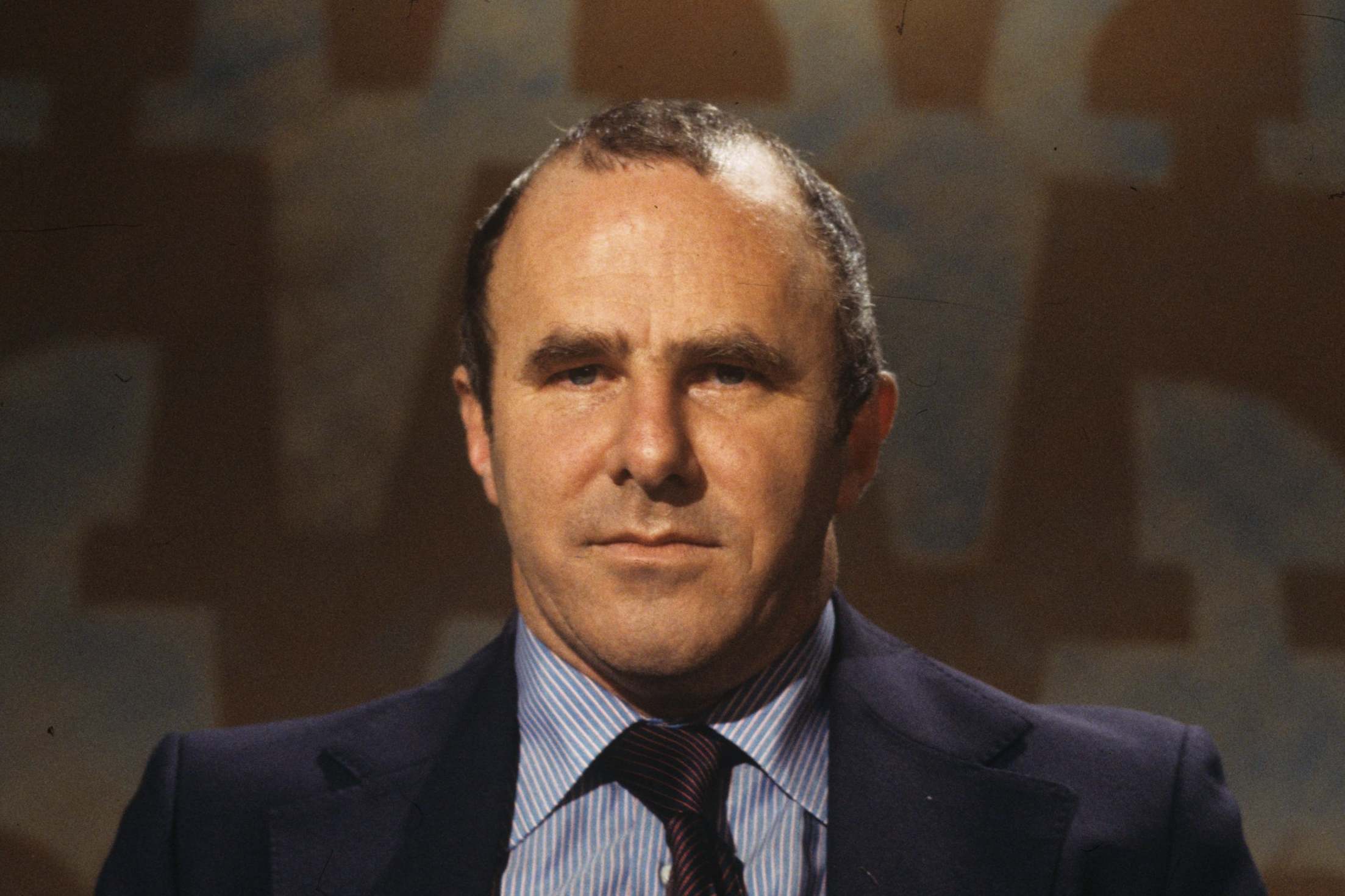

James, who has died aged 80, first became well-known as a television critic (virtually inventing that comic genre at The Observer from 1972-82 and returning to it in his final years with The Daily Telegraph), but he was also a novelist, poet, essayist, book reviewer, songwriter, television interviewer and documentary film-maker.

His rate of productivity in all these fields was prodigious. He published scores of books of fiction, essays, poetry and autobiography. In his later years he built one of the most comprehensive and ahead-of-its-time websites (www.clivejames.com) to showcase his life and work. Apart from containing an archive of his own voluminous works, the website uses film and audio to carry fresh his online interviews with leading figures in the arts and literature.

He related his obsessive creative energy to the early trauma he suffered when his father, just released from a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp at the end of the Second World War, died in an air crash on his way home to Australia in 1945. He believed that was the defining event in his life. “That’s when I found out the world was arbitrary,” he said. “At the age of six.”

He reflected on this experience in a poem describing a pilgrimage he made to his father’s grave in Hong Kong:

Back at the gate, I turn to face the hill

Your headstone lost again among the rest.

I have no time to waste, much less to kill.

My life is yours, my curse to be so blessed.

The effect, as someone said, was to make him “drive himself to the limit of what it is possible to achieve in one lifetime”.

He was born Vivian Leopold James in Sydney in 1939, but as a child chose the name Clive because, he said, Vivian (no matter how spelt) would forever be a female name after Vivien Leigh’s star performance in Gone With the Wind.

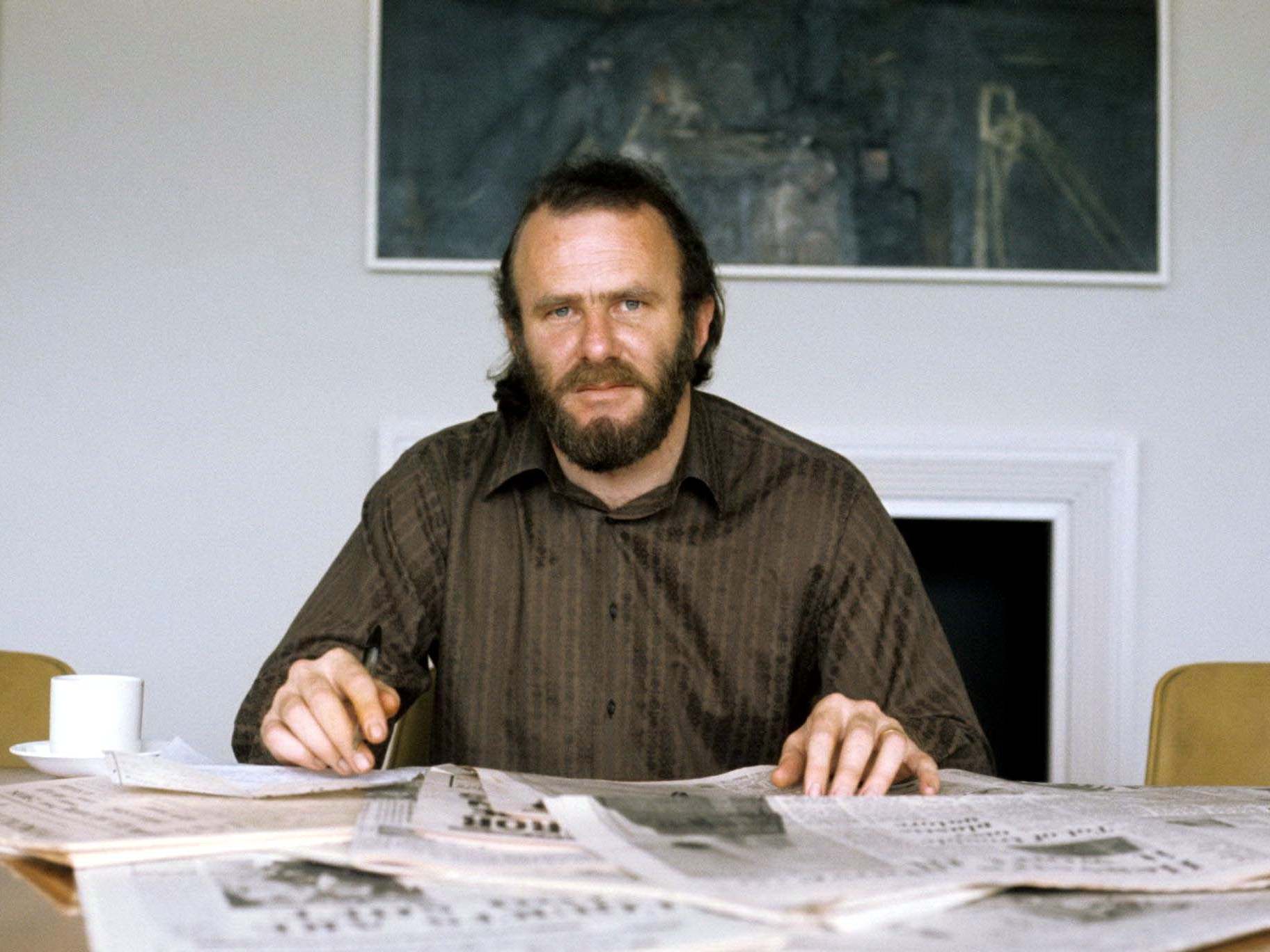

He attended Sydney Technical College and Sydney University. After a year on the Sydney Morning Herald, he sailed to England in 1961, part of a generation of talented Australians – Germaine Greer, Robert Hughes and Barry Humphries among them – who were to enrich British culture in their various ways. After three years of what he described as “a bohemian existence” in London, he went up to Pembroke College, Cambridge, at the age of 26. He became president of the Footlights and started writing for literary magazines.

Apart from the jokes that made him a “must read” on a Sunday, his strengths as a TV critic were his vast range of interests – “from ice-skating to Beethoven quartets”, as he once put it – and the Kenneth Tynan-like exactness of his descriptions of performers. Two examples: “Twin miracles of mascara, Barbara Cartland’s eyes looked like the corpses of two small crows that had crashed into a chalk cliff”; and “Perry Como gave his usual impersonation of a man who has simultaneously been told to say ‘Cheese’ and shot in the back by a poisoned arrow.”

James’ decision to go in front of the TV camera seemed like a surprising career move, but he swiftly became a popular success in series such as Cinema, The Late Clive James, Saturday Night Clive and Clive James on Television. He also made documentaries that achieved high ratings on subjects such as the Paris fashions, Las Vegas, Japan and Formula One, and interviewed stars like Katharine Hepburn, Jane Fonda and Mel Gibson. He pioneered TV travel “postcards”, reporting from a dozen of the world’s great cities.

He took pains, however, to maintain his intellectual credentials with reviews and essays in the literary weeklies: The Listener, the New Statesman, the Times Literary Supplement, The New York Review of Books and others. He also published collections of his TV criticism and literary essays and began a series of autobiographical volumes with the bestseller Unreliable Memoirs.

He viewed himself as an outsider, awkward and misplaced, and once said he felt “equally homeless in Britain and Australia”. He attributed his success on TV to the fact that he couldn’t be pinned down to a place in the British class system: “I counted as coming from nowhere.”

In his later years he went back to the stage, and on the road around Britain and Australia, as songwriter for Pete Atkin, a singer and composer with whom he had first collaborated at the Cambridge Footlights and the Edinburgh Fringe. They made six albums together in what has been described as “pop-folksy post-graduate rock’n’roll”.

He once said of himself: “That song I wrote in which the refrain goes, I’m a crying man that everyone calls the laughing boy – that’s pretty well true.” There is certainly a more sensitive and vulnerable note in his poems, especially those written in his later years. In “Son of a Soldier”, he wrote: “My tears came late. I was fifty-five years old/ Before I began to cry authentically.” He insisted: “The poetry, for me, is always the centre of the whole business.”

He was married to Prue Shaw; their marriage survived a late estrangement when an Australian model revealed an eight-year affair. He is survived by his widow and two daughters.

Clive James, writer and broadcaster, born 7 October 1939, died 27 November 2019

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments