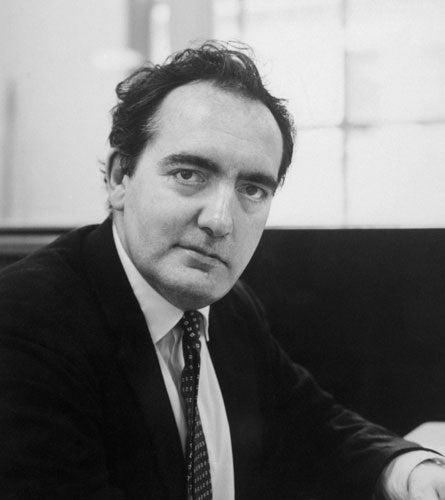

Clive Barnes: Revered dance and drama critic in London and New York

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The British writer Clive Barnes was acknowledged as one of the finest critics of dance and theatre, who revolutionised the way in which dance was criticised, and who for many years was the theatre critic for the New York Times in the days when that newspaper's reviews were powerful enough to make or break a show.

Although London critics generally attend the same performance, New York's critics are now able to take their choice of several performances, even though their reviews are published on an agreed date. But when Barnes was writing for the New York Times, in the 1960s and 1970s, all the critics attended the same "first night", after which they would rush up the aisles during the curtain calls to file their notices for the morning papers. Barnes, in contrast, could be spotted sauntering to the newspaper office across Times Square, where he would type with two fingers. His reviews were always carefully considered and fair. "He was the most honest, least opinionated person, who really loved the theatre," said the actor John Cullum.

Michael Riedel, a show business columnist at the New York Post, where Barnes was chief drama and dance critic for the last 30 years of his career, said, "I was in awe of the breadth of Clive's knowledge – of dance, classical music, literature, opera and art, as well as pop culture – he loved the Beatles. That knowledge informed his writing, but there was no pomposity or showing off – he had a really lovely, light, witty writing style, and refrained from cruel, personal attacks".

"I always wanted to be a part of the theatre," Barnes himself recently said. "I couldn't be an actor, because I stuttered, and I never knew what directors did – I'm not sure I even know today."

Clive Barnes was born in London in 1927 and raised by his mother after his father, an ambulance driver, deserted the family when Clive was seven. His mother, secretary to a theatrical agent, received complementary tickets to plays and to the ballet, and first took Barnes to the theatre when he was 10 years old, starting his lifelong enthusiasm for drama and dance.

He was educated at Emanuel School in south London, and then at King's College London, where he briefly studied medicine before discovering that the sight of blood made him faint. After two years National Service in the RAF, he went up to St Catherine's College, Oxford, to read English Language and Literature, and began writing about ballet for the university magazine, Isis.

After graduating with honours, he worked as an administrative officer for the London County Council to support himself while taking freelance work, notably for the magazines Dance and Dancers and The New Statesman. In 1953 he wrote his first book, Ballet in Britain Since the War, and in 1956 he joined the Daily Express as their second-string theatre critic, also covering dance for The Spectator. The same year he began an association with Dance Magazine, which was to last until the end of his life.

He had long been concerned that most newspapers sent their classical music critics to write about ballet ("They didn't know a thing about dance") and in 1962 he joined The Times as one of the first dedicated ballet critics on a London paper. One of the writers who brought a larger audience to ballet, Barnes considered Frederick Ashton one of the greatest choreographers, but also extolled the work of Martha Graham, Paul Taylor and Merce Cunningham. When George Balanchine presented the New York City Ballet in a season of Stravinsky, Barnes wrote, "Many choreographers have borrowed Stravinsky, but Mr Balanchine has continually paid interest on the loan". In 1967 he was the first dance critic to single out the 19-year-old Russian dancer, Mikhail Baryshnikov.

Barnes first became a regular contributor to the New York Times in 1963, and two years later he was offered the post of the paper's chief dance critic, prompting a move with his family to New York. In 1967 he became chief critic of theatre as well as dance, and for the next decade he was the most feared, but also respected critic in New York, his name as well known as any of the stars.

His idol was Kenneth Tynan, whom he credited with taking the pomposity out of theatre criticism, and Barnes himself was credited with taking a lot of the stuffiness out of the New York Times. Amazingly, he was the first of the paper's theatre critics to use the word "I", which had always been taboo; phrases such as "in this critic's opinion" were used instead. "I slipped 'I' into a review, then rushed home and sat by the telephone, fully expecting the managing editor to ring me up. But nothing. Not a peep. Three days later I used 'I' again, and eventually everyone more or less came round to it."

"He had a wonderful sense of humour and a self-deprecating wit," said Riedel. "When he first became theatre critic of the New York Times, the powerful producer David Merrick sent him a telegram stating that, 'The honeymoon is over'. Barnes cabled back, 'I didn't know we were married, and I didn't know you were that kind of boy.' Among the playwrights he championed were Harold Pinter, Tom Stoppard and David Mamet.

In 1978, after the New York Times decided to let Barnes cover dance but replace him as theatre critic, he accepted an offer from the New York Post as drama and dance critic. He was also a regular broadcaster, a consulting editor and writer for Dance Magazine, the New York correspondent for The Stage magazine in London and a lecturer and prolific contributor to other journals. "I'm your typical working-class over-achiever," he said. His association with the Post was to continue until just before his death ("I've run longer than Cats"); he filed his last dance review three weeks ago.

Tom Vallance

Clive Alexander Barnes, dance and drama critic: born London 13 May 1927; Administration Officer, Town Planning Department, London County Council 1952-61; Chief Dance Critic, The Times 1961-65; Executive Editor, Dance and Dancers, Music and Musicians and Plays and Players 1961-65; a London correspondent, New York Times 1963-65; Dance Critic 1965-77, Drama Critic 1967-77; CBE 1975; Associate Editor and Chief Dance and Drama Critic, New York Post 1977-2008; married 1946 Joyce Tolman (marriage dissolved), 1958 Patricia Winkley (one son, one daughter; marriage dissolved), 1985 Amy Pagnozzi (marriage dissolved), 2004 Valerie Taylor; died New York 19 November 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments