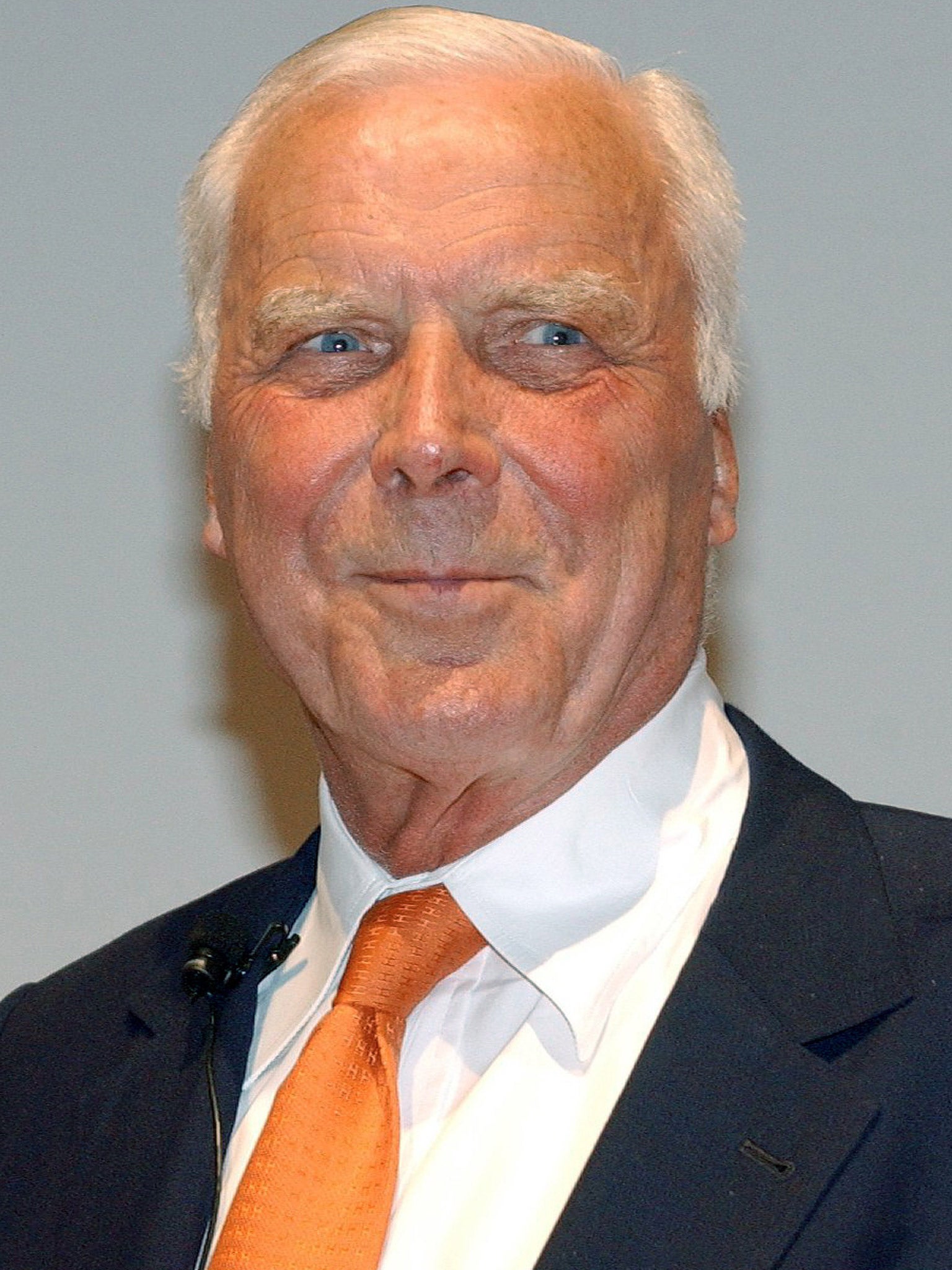

Claus Jacobi: Editor jailed during the 'Spiegel' affair

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Claus Jacobi was the editor-in-chief of the German weekly news magazine Der Spiegel from 1962 until 1968. He was arrested during the Spiegel scandal – and was referred to by many of his colleagues as "journalist of the century".

On 10 October 1962, Der Spiegel published a piece headlined "Bedingt abwehrbereit" ["conditionally prepared for defence"]. Written by Conrad Ahlers, it was based on an analysis of Nato manoeuvres which had taken place under the codename Fallex 62 involving a simulated Soviet nuclear attack resulting in heavy devastation and casualties in Germany and Britain. It claimed that civil defence and communications were totally inadequate, that the West German armed forces, Bundeswehr, could not be properly mobilised, and that the Defence Minister Franz-Josef Strauss and his American colleagues could not agree on strategy.

The publication of such secret material was a violation of German law but Rudolf Augstein, Der Spiegel's owner, refused to divulge the source of the leak. Strauss and Chancellor Adenauer ordered a search of the magazine's office and Augstein and Jacobi and others were arrested; Ahlers was arrested on holiday in Spain. With the police present, Jacobi finished editing the current issue but the proofs had to be vetted by the investigating judge – an act of censorship which violated the German constitution. At one point investigators searched the beds of Jacobi's children, seizing their drawings as evidence. The matter looked like becoming an ugly farce.

The arrests caused a storm, with much of the press and the opposition Social Democrats condemning the action; street demonstrations followed. The minor coalition, FDP, at first remained loyal to Adenauer but resigned as it became clear that the Minister of Justice, FDP's Wolfgang Stammberger, had not been consulted. They refused to rejoin the government unless Strauss went. Their stand and the continuing protests from the public led to his resignation. Augstein was eventually in jail for 103 days, Jacobi for 18. The legal case against him was finally dropped in March 1965.

Claus Jacobi was born in Hamburg and grew up in the Third Reich, experiencing the devastating raids on his native city. At war's end he was an 18-year-old navy cadet. He started his journalistic career in 1946 as a cub reporter in the local press, then was taken on by the rising weekly Die Zeit, where he stayed for four years.

He was poached from Die Zeit by Spiegel's dynamic owner, Rudolf Augstein, by the offer of three times his Zeit salary on another increasingly important investigative weekly. His first big story appeared on 13 June 1956, on the Greet Hofmans scandal in the neighbouring Netherlands. Hofmans, a faith healer, had been a friend and advisor of Queen Wilhelmina for nine years and her influence had split the royal family. It was thought that she was influencing the Queen in a pacifist direction at the height of the Cold War and the CIA were looking on in dismay.

Jacobi was Der Spiegel's joint editor-in-chief, with Johannes Engel, from 1962 until 1968. The Spiegel affair had marked a watershed and led to a new liberalism in West Germany and greatly increased the prestige of the three rival weeklies. Spiegel's circulation soared, and it suddenly became famous internationally, but Jacobi left in 1968 feeling that Augstein was pushing it too far in a political direction.

After working briefly at the weekly, Stern, he moved to the Sunday, Welt am Sonntag, as editor-in-chief. After a brief encounter with the economic weekly Wirtschaftswoche he returned to the daily Die Welt in 1974.

Among the many encounters Jacobi recalled during his colourful career was tramping with Albert Schweitzer in the jungle, entertaining Richard Nixon with Russian vodka and flying with Bobby Kennedy, and he was with Chancellor Willy Brandt on his historic trip to Erfurt, East Germany, in 1970. He corresponded with the East German spymaster Markus Wolf and the spy writer John Le Carré. Although not a Catholic, he was most impressed, he said, by his meeting with Pope John Paul II.

"Jaco", as he was known to his friends, was friendly, good-looking and charming, especially to women. In 1971 he married the painter and children's charity founder, Heiki, who died in her sleep in 2012. In his last years his son Sven looked after him and was by his bedside when he died.

Claus Jacobi, journalist: born Hamburg 4 January 1927; married 1971 Keiki (one son); died Hamburg 17 August 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments