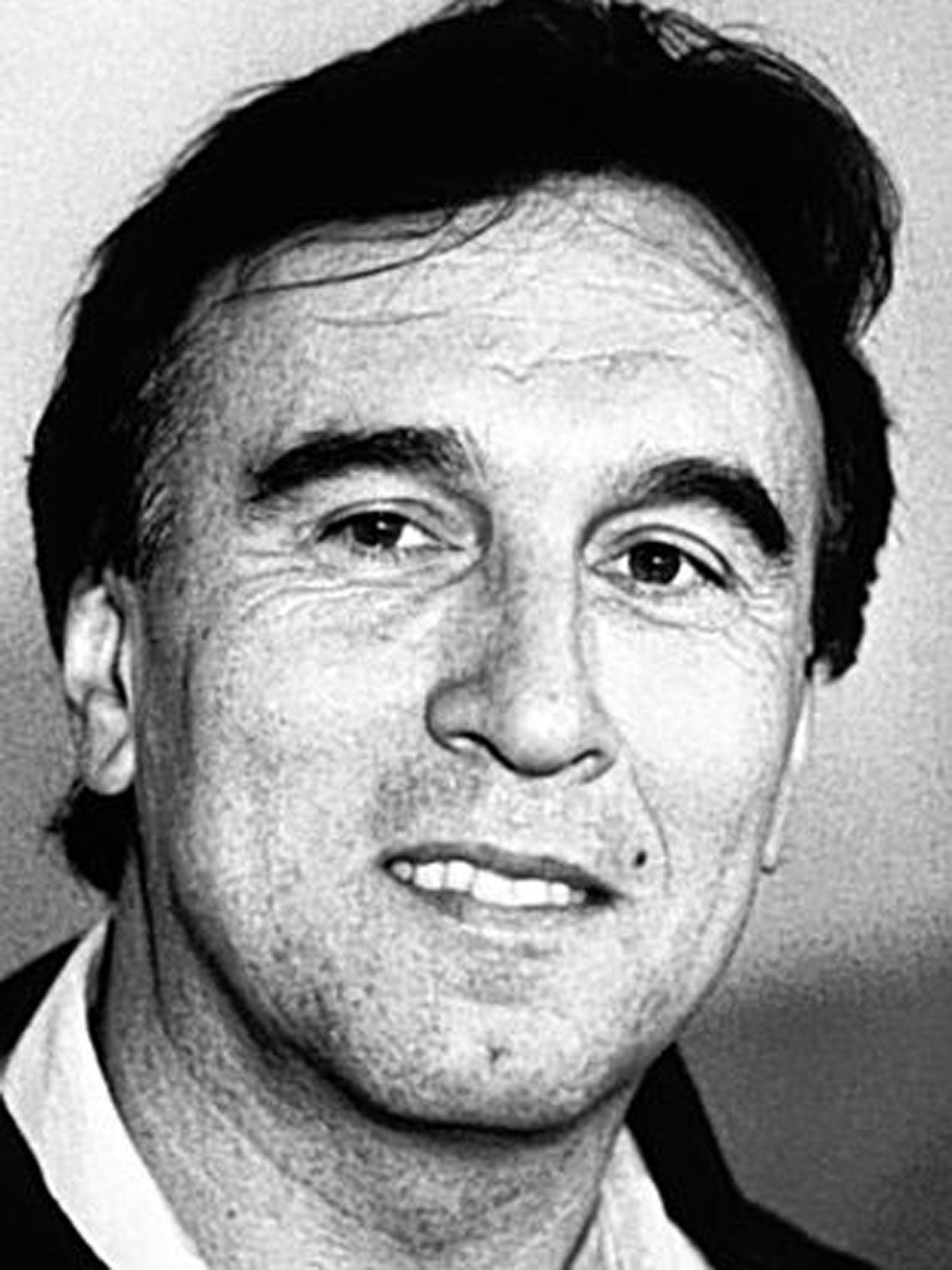

Claudio Abbado: Conductor whose work in Milan, Berlin and elsewhere led him to be hailed as one of the 20th century's finest

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Claudio Abbado was one of the best-respected conductors of the second half of the 20th century; indeed, when he was diagnosed with cancer in 2000, his career seemed to have come to its term with the century itself, but with customary determination, half-hidden by his modest manner, Abbado pulled himself back from the brink of death to produce another decade of visionary music-making.

Abbado enjoyed some of the most prestigious appointments in the classical world, with La Scala, Milan, the London Symphony and Berlin Philharmonic Orchestras and the Vienna State Opera among his fiefdoms, to the extent that he was sometimes referred to as one of the most powerful men in his discipline – and yet he never used that power: he was reserved, soft-spoken (when he spoke at all) and completely uninterested in celebrity status.

He preferred to let his music-making speak for itself: it was on the podium, not in interviews, that a passionate communicative power was unleashed, resulting in performances of fierce intensity. His slight figure, unassertive manner and understated rehearsal technique disguised a steely pursuit of perfection – but he placed his trust in his musicians and reserved their energy for the concert itself. He generally conducted without a score, the better to maintain eye-contact with his players. Like all great musicians he had an inherent sense of pulse and pace, of how a larger span of music can flow across different tempos. Structures that sprawl in some hands – like the Mahler symphonies – became natural and logical in his.

He was born into a musical family, the third of the four children of Michelangelo Abbado, an esteemed Milan violinist, and Maria Carmela, a pianist and writer of children's books; his older brother, Marcello, is a noted composer, conductor and pianist. Family history claims descent from Abdul Abbad, a Moorish chieftain expelled from Spain in 1492. His parents taught him violin and piano from the age of six. Claudio's calling came when he was eight and heard a performance of Debussy's Nocturnes at La Scala: "I immediately felt a desire to create this music one day myself," he recalled; "I decided to become a conductor". Attending postwar rehearsals by Furtwängler and Toscanini, he was appalled by Toscanini's podium histrionics and resolved to make his mark in a calmer manner.

His lifelong leftist leanings were shaped by his childhood in Mussolini's Italy, where his parents were active in the anti-Fascist resistance, offering aid to partisans and helping Jewish refugees escape to Switzerland; his mother was imprisoned for sheltering a Jewish child. He had a direct brush with the Nazis when he wrote a graffito, "Viva Bartok!", on a wall, and the Germans, unfamiliar with contemporary Hungarian music, rifled the family house, looking for a partisan called Bartok.

Piano and composition lessons preceded his enrolment in the Conservatorio Giuseppe Verdi in Milan, whence he graduated in 1955; he earned pocket money as a church organist. His first conducting experience came with the Orchestra d'Archi di Milano founded by his father. The summer of 1955 he spent studying with Friedrich Gulda at the Salzburg Festival and those of 1956 and '57 in the conducting classes of Alceo Galliera and Carlo Zecchi at the Accademia Chigiana in Siena – where he met two future podium colleagues, Daniel Barenboim and Zubin Mehta.

At Mehta's urging he went to the Academy of Music in Vienna, a city that was to feature prominently: a scholarship allowed him to study with Hans Swarowsky, whose undemonstrative and precise, analytical approach had its effect on his style, intellectually and technically – one of Swarowsky's methods was to teach his students to conduct with one hand behind their backs. Mehta was a fellow student, and the friends joined the bass section of the Musikfreunde chorus so they could observe its conductors at work; among those under whom they sang were Herbert von Karajan, Hermann Scherchen, George Szell and Bruno Walter.

Abbado first attracted international attention in 1958 when he won the Koussevitzky competition at Tanglewood. Invitations came to conduct a number of American orchestras; Abbado, already showing an indifference to astute career moves, preferred to return to Europe. His debut there followed a year later, when he conducted Prokofiev's opera The Love of Three Oranges in Trieste. His debut at La Scala followed in 1960 with a concert in the Piccola Scala, marking the tercentenary of the birth of Alessandro Scarlatti.

In 1963 he won the Mitropoulos Competition in New York (conducting badly, he said), which brought a one-year assistantship with Leonard Bernstein; and at the Salzburg Festival in 1965, at the invitation of Herbert von Karajan, he stood in front of the Vienna Philharmonic for the first time, conducting music closer to his heart: Mahler's Second Symphony. (His debut in Vienna itself followed two years later.)

Two more important debuts came later in 1965, with the Hallé Orchestra (his first appearance in Britain) and the LSO. He first worked with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1966. In 1967 he made his first recording for Deutsche Grammophon, a relationship that would endure for over four decades. Another major debut followed in 1968, with Don Carlo at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden – his first appearance there and his first Verdi opera.

In a series of leading positions at La Scala from 1968 he dragged the conservative institution and its audiences into the second half of the 20th century, programming modernist composers like Luigi Dallapiccola and Luigi Nono, commissioning new works and expanding the repertoire in other directions, bringing in younger, less-well-off listeners, and taking the orchestra to play in factories. Eventually the internal politicking became too much for him and, having resigned already and returned, in 1986 he left for good.

In 1971 he became principal conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic. His engagement with Viennese music-making deepened: he headed the Vienna State Opera from 1986-91, expanding the repertoire. In 1987 he became General Musikdirektor of the city itself and in 1991 founded a composers' competition there.

His first formal position with the London Symphony Orchestra was as principal guest conductor in 1972. He became principal conductor in 1979 (succeeding André Previn) and was music director from 1983-86. In parallel (1982–85) he was principal guest conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

In 1990 he was named chief of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra from 1990, succeeding Herbert von Karajan, who had ruled the roost there for 35 years. Abbado's collegial, anti-dictatorial style could hardly have been more different from Karajan's and some of the musicians resented the responsibility that devolved on to them; the critics likewise took some time to adapt. As in Milan, Abbado blew the stuffiness out of the Berlin programmes.

In all his orchestras he encouraged his musicians to listen to one another, as if they were playing chamber music. As a result, the Berlin sound moved away from Karajan's patrician opulence to a leaner, cleaner, more texturally detailed palette, resulting in 2000 in what is probably the finest cycle of Beethoven symphonies yet recorded. Abbado's illness in 2000 – cancer required the removal of his stomach – shook the classical world. His resignation of the Berlin post in 2002 suggested the end was near, but he made a near-miraculous return to precarious health.

One constant of Abbado's career was the care and attention he gave to younger musicians. Fledgling conductors were struck by his generosity, patience and enduring interest in their progress, and he was an enthusiastic founder of orchestras. He set up the Filarmonica della Scala, and the European Community Youth Orchestra followed in 1978, the Chamber Orchestra of Europe in 1981 and in 1986 the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra, which in 1997 begat the Mahler Chamber Orchestra.

Work with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra from 2003 seemed to act as therapy for Abbado, who handpicked its mostly young musicians and took pride in the intensity of its performances. It was with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra, on 26 August last year, that he gave his last concert.

Claudio Abbado, conductor: born Milan 26 June 1933; married 1956 Giovanna Cavazzoni (divorced 1968; one son, one daughter), secondly Gabriella Cantalupi (one son); one son with Viktoria Mullova; died Bologna 20 January 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments