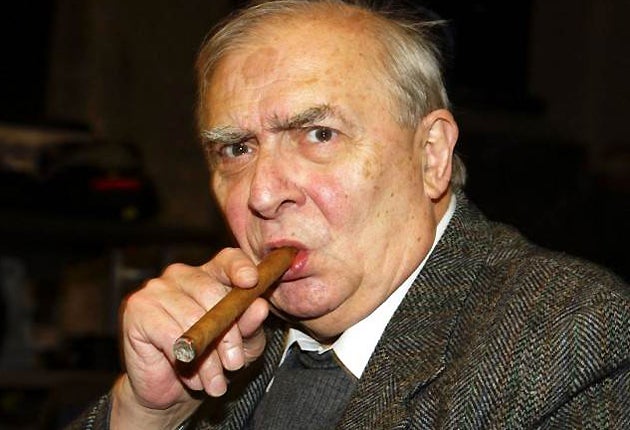

Claude Chabrol

New Wave director known for his menacing thrillers set in bourgeois milieu

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Claude Chabrol was the first of a young group of French film critics who broke through into directing in the late Fifties and formed the Nouvelle Vague, the movement that was to have a profound effect on European cinema with its rejection of studiobound traditions and constraints. He was noted especially for atmospheric thrillers, in which the claustrophobic world of small-town convention masked an underlying sense of menace.

After making a strong impression with his first film, Le Beau Serge (1958), which, like many of his better films, dissected the world in which he grew up, that of the urban petit-bourgeoisie, he followed it with such acclaimed movies as Les Cousins (1959) and The Girls (1960), then after a fallow period when he made several commercially driven but critically decried movies, he returned to inspired form with Les Biches(1968), TheUnfaithful Wife(1969), and what is arguably his masterpiece, The Butcher (1970), which starred his then wife, Stéphane Audran.

Born in Paris in 1930 into the sort of bourgeois background that he would examine in many of his finest movies, he intended to enter the family pharmaceutical business, but after national service, while studying pharmacology at the University of Paris, he became interested in the cine-club activities and entered the film business as a publicity officer in the Paris bureau of 20th Century-Fox.

His first film criticism appeared in the magazines Arts and, most significantly, in Cahiers du Cinema, founded in 1950 by the critic André Bazin. It was on the pages of Cahiers du Cinema that Chabrol and his cohorts developed the auteurtheory that films should be judged in the context of their director's personal vision.

In 1955 he and François Truffaut interviewed Alfred Hitchcock on the set of To Catch a Thief, and in 1957 he coauthored, with future New Wave director Eric Rohmer, an analytical book on Hitchcock, whose influence is notable in several of Chabrol's own films. The following year, money that his first wife had inherited enabled him to finance his own first film as a writer /director, Le Beau Serge, and to set up his own production company, AJYM, through which he was able to finance the first films of such Nouvelle Vague directors as Rohmer, Jacques Rivette and Philippe De Broca. (He is credited as "technical consultant" on Jean-Luc Godard's first film, Breathless, 1960).

The partly autobiographical story tells of a young man who returns to the village of his childhood in Sardent (where Chabrol himself was brought up), and tries to save the marriage of his best friend, who has become an al-coholic after the birth of his Down's syndrome child. Le Beau Sergewas a great critical and commercial success and is regarded as the start of the New Wave.

The same leading actors, Gérard Blain and Jean-Claude Brialy, starred in Chabrol's next film, Les Cousins(1959), in which a shy young man from the country stays with a dilettante cousin in Paris and is constantly outclassed by him. American critics found the tragic tale depressing, Bosley Crowther of the New York Times stating, "M. Chabrol is the gloomiest and most despairing of the new creative French directors. His attitude is ridden with a sense of defeat and ruin." But in Europe Les Cousins, beautifully fashioned and photographed on a low budget, was generally hailed as another fine work, and it was awarded the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival.

The Girls (1960) was one of Chabrol's most controversial films, a depiction of two days in the lives of four salesgirls who dream of lives away from their tedious existence; one works parttime in a cheap music hall, one dreams of bourgeois marriage, one wants a good time and one yearns for romantic love but is strangled by a sex murderer.

An early feminist work in which the director has compassion for his heroines but contempt for their dreams, it is now considered a masterpiece, though its irony was missed by many, Variety stating, "Chabrol is a clever craftsman but he shows no definite attitude towards his poor puppet girl victims." The film's failure is often blamed for steering Chabrol towards a series of lacklustre commercial ventures, the best of which included Bluebeard (1963), a surprisingly comic view (written by Françoise Sagan) of the infamous French mass murderer, and Chabrol's contributions to two omnibus films, Les Plus Belles Escroqueries("The Beautiful Swindlers", 1963) in which his brief account of a German tourist buying the Eiffel Tower was considered the highlight, and Paris Vu Par... ("Six in Paris", 1965) with Chabrol again coming off best with the tale of a small boy who blots out his parents' quarrelling with a pair of earplugs, but then fails to hear his mother's cries for help.

The Champagne Murders (1967) was an ill-advised attempt to reach the international market (the cast was topbilled by Anthony Perkins) with a contrived Hitchcockian tale of blackmail and murder, but happily the following year Chabrol made Les Biches, an elegantly witty tale of a bisexual ménage à trois starring Stéphane Audran (who won the Best Actress award in Berlin) as a rich woman who takes a young student (Jacqueline Sassard) to St Tropez where their idyll is disrupted by a local architect (Jean-Louis Trintignant), who makes love to both ladies. Les Bicheswas hailed as Chabrol's best work and a return to form for the director who was now ranked by critics as equal to his New Wave brethren Truffaut and Godard.

He next made one of his greatest films, The Unfaithful Wife (1969), in which a man's murder of his wife's lover ultimately revives the deep passion of the married pair. Utilising one of his favourite themes - the turbulence beneath the outward calm of a bourgeois life and the necessity for family rituals, such as meals, to be continued - Chabrol produced a masterwork, prompting critic Margot Kernan to observe, "Few directors are more skilful at using a sensuous cinematic style to suggest a world of minimal feelings and reified relationships." The film cast Stéphane Audran as "Hélène" in the first of a superb cycle of films dealing with marital infidelity leading to murder.

In This Man Must Die (1969), based on a thriller by C Day Lewis (under his pseudonym Nicholas Blake), Caroline Cellier plays Hélène, the sisterin-law of a despotic car mechanic suspected of being a hit-and-run driver. Chabrol expressed the desire to make the film in the style of Fritz Lang, and the result was one of his most engrossing, and popular movies.

It was followed by The Butcher, a brilliant study of repression, passion and guilt, in which Audran, again named Hélène, was compelling as a cultured but emotionally stilted school-teacher who begins to suspect that the town butcher (Jean Yanne), with whom she is falling in love, may be the serial killer who is terrorising the town. A haunting tale that incorporates all of Chabrol's favourite themes, it is also one of his most moving works.

In the taut and tense thriller The Breakup(1970), Audran was a battered wife fighting to keep her sons despite the machinations of her husband's family. It was followed by Just Before Nightfall (1971), a film that reversed The Unfaithful Wife by featuring Audran as the wife of a man who kills his mistress but finds himself forgiven by both his wife and the victim's husband. In the final scene, the killer uses the word juste 17 times in different ways, echoing Chabrol's view that justice has more than one interpretation, though some critics felt that his preaching of a moral point kept him too removed from the subject.

The film heralded another patchy period in Chabrol's career, but he found favour again with Violette Nozière(1977), his account of a sordid true story of a promiscuous Parisian who contracts syphilis and poisons her parents. Later he made a surprising excursion into lush period drama with an adaptation of Madame Bovary (1991), but though he worked consistently - he made more than 50 films - he never regained the quality or stature of the great years, though La Cérémonie (1995), based on a Ruth Rendall thriller and starring Isabelle Huppert, won praise.

His work for television included The Eye of Vichy(1993), a documentary about occupied France. His last film was Bellamy (2009) starring Gérard Depardieu. The Mayor of Paris, Bertrand Delanoë, described Chabrol as "the inventor of inspired, rich and profoundly human movies. He produced an immense and particularly inspired body of work that stands today as a monument of French cinema".

Claude Chabrol, film director: born Paris 24 June 1930; married 1952 Agnès Goute, (two sons, marriage dissolved), 1964 Stéphane Audran (one son, marriage dissolved), 1983 Aurore Pajot (one daughter); died 12 September 2010.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments