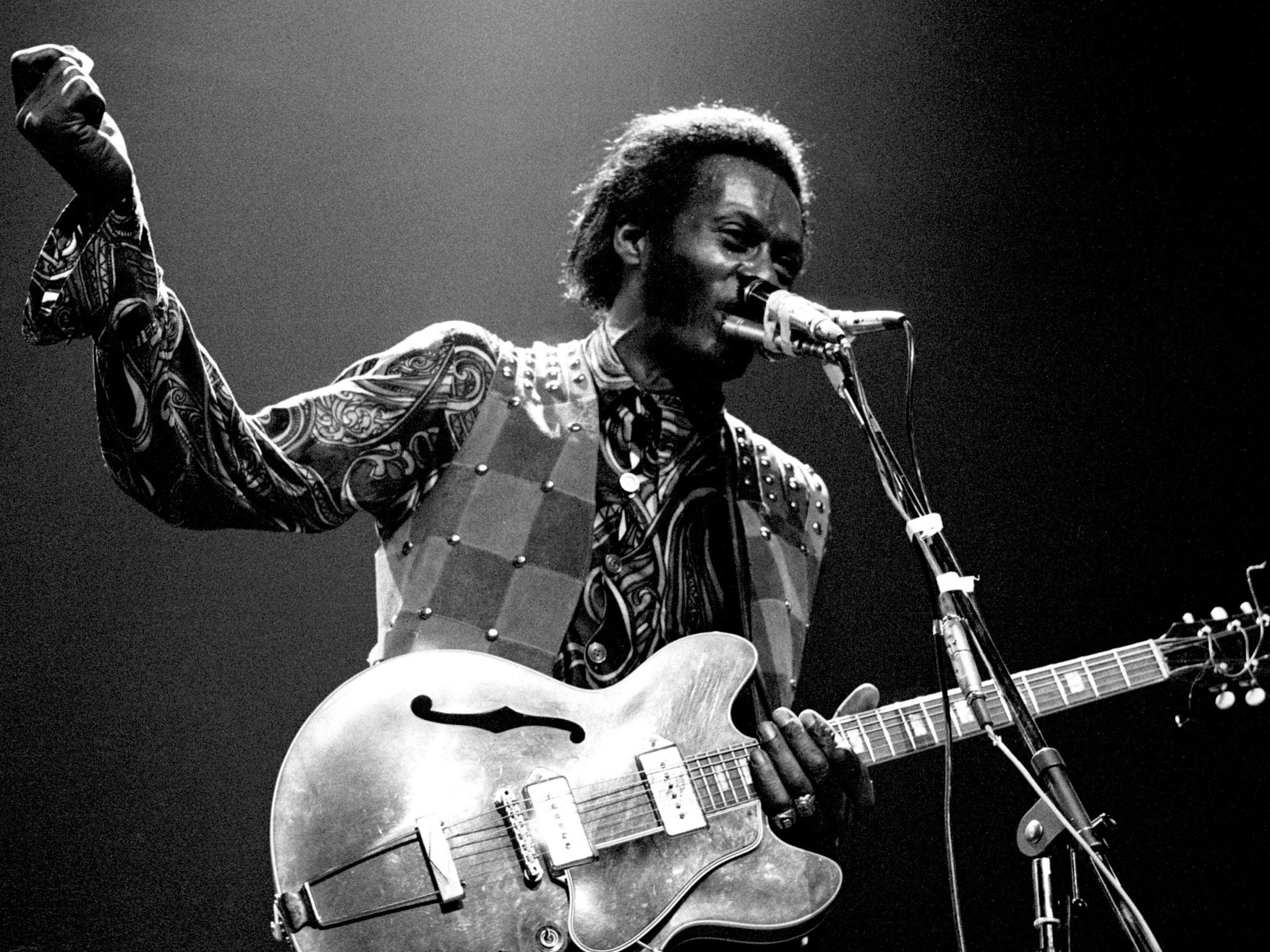

Chuck Berry remembered: 'There is not a rock musician alive who has failed to fall under his spell'

'He one of the all-time great poets, a rock poet you could say,' says John Lennon in The Beatles Anthology

The impact and influence of Chuck Berry on popular music over more than six decades – as a lyricist, singer, guitarist and showman – far outstripped the considerable sales of his distinctive, pioneering recordings, which served as a bridge between black rhythm ’n’ blues and white rock and roll.

The Beatles and Rolling Stones built their early careers around the American’s witty teen epics, covering nine and 13 Berry numbers respectively. Others who have recorded his songs range from Elvis Presley, Cliff Richard and Johnny Hallyday through The Animals, Kinks, Faces, AC/DC, Status Quo and Sex Pistols to Jimi Hendrix, Emmylou Harris, David Bowie, Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen. The Beach Boys used the tune of his “Sweet Little Sixteen” as the basis for “Surfin’ USA” and had to co-credit Berry and Brian Wilson as writers to avoid a lawsuit.

The eminent music historians Pete Frame and John Tobler, in their 1980 book Twenty-Five Years of Rock, decreed: “There is not a rock musician alive who has failed to fall under his spell at one time or another.”

Meanwhile, in The Beatles Anthology, John Lennon is quoted as having elevated Berry above the status of mere songsmith. “(He) is one of the all-time great poets, a rock poet you could say … We all owe a lot to him, including Dylan. In the Fifties, when people were virtually singing about nothing, Chuck Berry was writing social-comment songs, with incredible metre to his lyrics.”

Lennon took the vocals on Berry’s “Rock ’n’ Roll Music” on the Beatles For Sale album in 1965, eight years after the original single reached No 8 in the US chart. He reprised it during 1979’s "Let It Be" sessions, and when, as an ex-Beatle, he released his 1975 covers set Rock ‘n’ Roll, it included Berry’s “You Can’t Catch Me” and “Sweet Little Sixteen”.

Berry, who has died at the age of 90, was born Charles Berry in St Louis, Missouri, one of six children to Henry, a Baptist deacon, and Martha, a school principal. The future rock innovator was 15 when he first played publicly at the high school he attended.

When he was 19, however, came the first of the tangles with the law that – along with his fabled obsession with money – intermittently tarnished his reputation. Berry was convicted of robbing three shops in Kansas City and stealing a car at gunpoint. He was sent to a young offenders’ institution for two and a half years, being released on his 21st birthday.

Working variously as a janitor, car-assembly worker, carpenter and hairdresser, he married, became a father and performed with local blues groups in order to fund his interest in photography. In vocal terms, he later acknowledged a debt to the crooner Nat “King” Cole, whose precise diction he revered. Lyrically, he was inspired by the cool wit and storytelling flair of bandleader Louis Jordan. Both were among the first black “cross-over” artists to achieve popularity with the mainstream – ie. white – audience. He also incorporated facets of the guitar style of the blues picker T-Bone Walker.

Berry’s opportunity to emulate his heroes arrived in 1955, and although success came suddenly in one sense, at 28 he was hardly an overnight sensation. While playing in St Louis in a trio led by pianist Johnnie Johnson he had introduced an element of country music – what he called “black hillbilly”. He took one song, “Ida Red” by the Texan king of Western swing, Bob Wills, to an audition for Chess Records in Chicago, for which he had been proposed by the great Mississippi bluesman Muddy Waters.

The label was home to Waters, Sonny Boy Williamson, Bo Diddley and Little Walter. Its founder, Leonard Chess, saw the commercial potential of Berry’s re-working of “Ida Red” as “Maybellene” and installed him in the studio with a band that included Johnson on piano to record it on 21 May 1955. Within four months the single reached No 1 in Billboard’s R & B chart and No 5 nationally, selling a million copies.

In Crosstown Traffic, Charles Shaar Murray’s biography of Jimi Hendrix – who cited Berry as his favourite artist and recorded “Johnny B Goode” – the music critic recounted how Berry toured on the back of “Maybellene’s” success. Parts of the United States remained racially segregated and some promoters did not realise he was black until he arrived to play.

“He was hurriedly and embarrassedly paid off at one such venue,” reported Murray. “As he prepared to leave, he heard the white band who had been hired to back him playing his hit.”

Surprisingly, given how well known the song became after The Beatles and Electric Light Orchestra reinterpreted it, “Roll Over Beethoven” only scraped into the American top 30 in 1956. Part of the soundtrack to the film Rock, Rock, Rock, the lyric urged a radio DJ to ignore classical music, which was for squares, and play rhythm ’n’ blues. This was Berry articulating the generational divide in the US and the UK after the end of post-war austerity, with several verses concluding: “Roll over Beethoven and tell Tchaikovsky the news.”

Pete Frame, noting in his book The Restless Generation that Rock, Rock, Rock combined a feeble plot with limp pop, suggested its redeeming feature was Berry “ducking and bobbing and looking into the camera to see if anybody out there was on his wavelength”.

For the next two years, the hits kept coming. “School Days” provided his British breakthrough, albeit at No 24, and made No 5 in the States. Berry was now 30 but had his finger on the pulse of teenage rebellion. The lyric was the story of a day that started with “American history and practical math/ You’re studying hard and hopin’ to pass”. It dragged through to lunchtime and into the afternoon, until three o’clock. Then it was into the “juke joint” where “You drop the coin right into the slot/ You’re gonna hear somethin’ that’s really hot”.

“Rock ’n’ Roll Music”, “Sweet Little Sixteen”, “Carol” and “Johnny B Goode” were all major American hits before the Fifties ended. (The latter was the only rock and roll song on a disc carrying “Music from Earth” that was sent into space as part of the Voyager mission in 1977 – alongside Beethoven, coincidentally).

A measure of the depth of Berry’s catalogue of 150-second classics was that “Around and Around” and “Reelin’ and Rockin’”, staples of the repertoires of countless bands over the ensuing half-century, were only B-sides, as was “Brown-Eyed Handsome Man”, a posthumous hit for Buddy Holly.

Astonishingly, Berry’s own version of “Memphis, Tennessee”, another of his great “story” songs complete with the teasing pay-off line revealing that “Marie is only six years old”, did not enter the US hit parade, although Johnny Rivers’ 1964 cover peaked at No 2 in 1964.

By that point Berry had endured a second, potentially career-ending prison sentence. In December 1959, while on tour in Texas, he met a 14-year-old Apache Indian girl, Janice Escalante. He invited her to work as a waitress in his racially integrated St Louis nightclub, which led to his being convicted for taking a minor over the state line “for immoral purposes”. He was fined $10,000 and jailed for three years.

In his 1987 autobiography, to which Springsteen contributed the foreword, he maintained he had used his time inside studying accounting and business management and law (although what he learned could not prevent his being jailed a third time in 1979, when he served three months for tax-evasion).

Berry could have been a pariah, or largely forgotten, by the time he was freed 20 months into his term in 1963; the pop world had undergone a revolution while he was out of the public eye. Happily for him, it transpired that he had been instrumental in inspiring the seismic shifts brought about by The Beatles, who now championed him.

Muddy Waters, interviewed in 1977 by Charles Shaar Murray in the New Musical Express, saw his own and Berry’s influence on the “British Invasion” groups as having simultaneously helped popularise black music. “The Beatles did a lot of Chuck Berry, the Rolling Stones did some of my stuff. That’s what it took to wake up the people in my own country. There was a time when a kid couldn’t bring that music into a father and mother’s house. ‘Don’t bring that nigger music in here’.”

Mick Jagger and his cohorts had established a reputation as a “live” act with a set peppered with Berry’s standards. When they landed their first residency, at the Crawdaddy club in Richmond-on-Thames in 1963, audiences clamoured for “Route 66”, not a Berry tune but one to which he had applied his unique style. They kept it for the encore.

The Stones’ 1963 debut single was Berry’s “Come On”, the lament of a man who can’t even get his car started since he and his “baby” parted. “I wish somebody’d come along and run into it and wreck it,” he sang.

When Berry’s version appeared, in 1961, the UK charts featured the clean-cut Eden Kane, John Leyton and Helen Shapiro. Britain was not ready, it seemed, for a couplet such as “Every time the phone rings sounds like thunder/ Some stupid jerk tryin’ to reach another number”. Possibly in a nod to conservative sensibilities, the Stones changed “jerk” to “guy”, but Dylan and Lennon were surely taking notes.

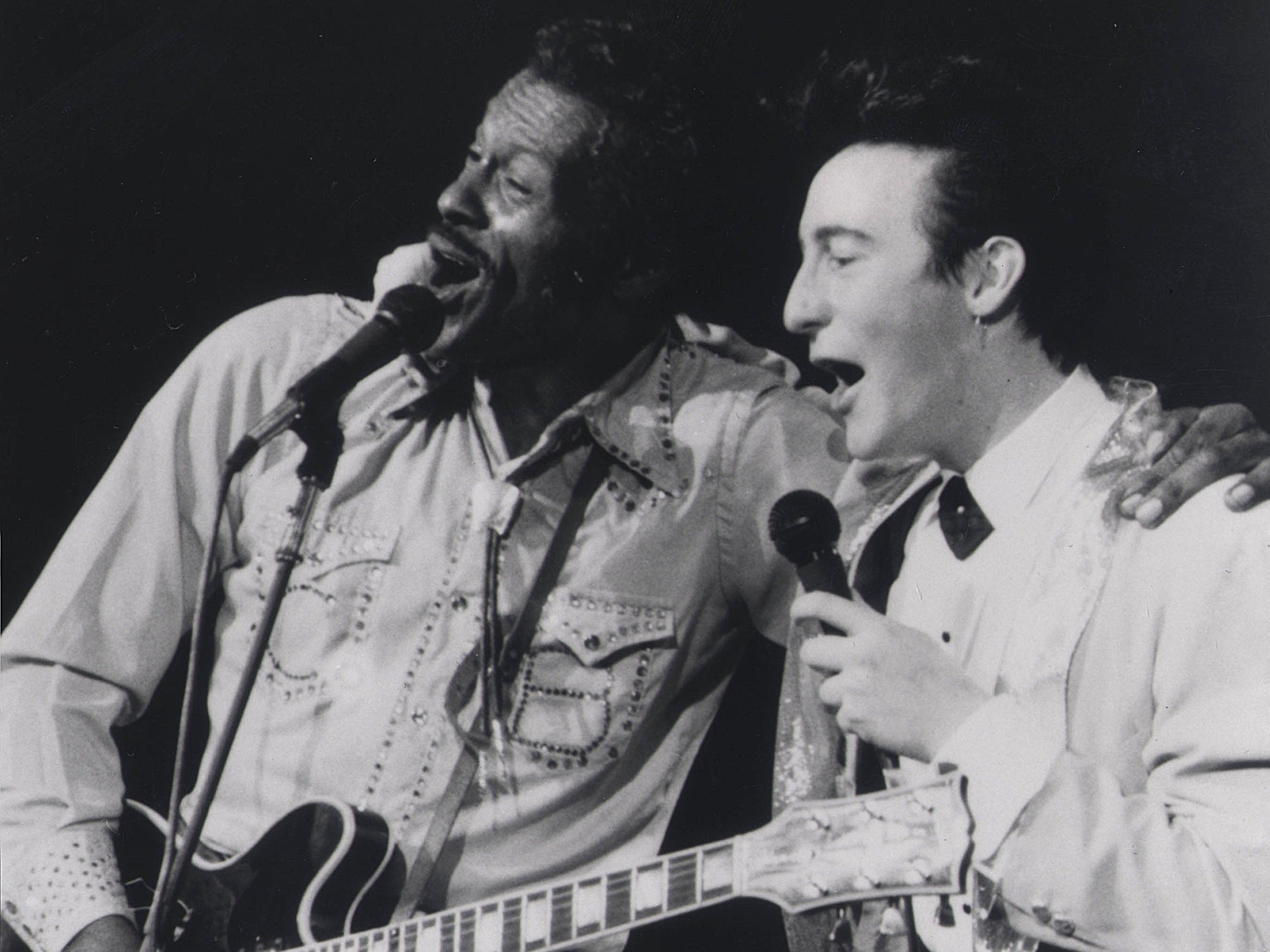

Springsteen, incidentally, admitted he came to love Berry’s music through listening to the Stones’ early LPs. The pair performed together several times – a natural alliance of two men who wrote so many songs about cars and women, it might be argued – with the E Street Band backing the veteran rocker at a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame concert in 1995.

Berry had been inducted into the Hall of Fame, in 1986, when Keith Richards made the address. “It’s hard for me to induct him,” he said, “because I lifted every lick he ever played”. The same year, to mark Berry’s 60th birthday, Richards and Eric Clapton guested in two concerts that were captured in a documentary film which took its title, Hail! Hail! Rock ’n’ Roll, from “School Days”.

In the mid-Sixties, as Richards’ riffs drove the Stones’ rise, Berry reclaimed his place among the best-sellers on both sides of the Atlantic: 1964 and ’65 saw him deliver sides such as “No Particular Place To Go” (a funny revamp of “School Days”), “Nadine” and “You Never Can Tell”.

The brilliant “Promised Land” inexplicably fared less well, though it prompted memorable covers by Presley (a UK top 10 hit and album title-track in 1975) and by Cajun rocker Johnnie Allan.

He toured relentlessly. But instead of his shows being the life-affirming experience they should have been, with Berry executing his famous “duck walk” across stage while playing one of his trademark guitar solos (as mimicked by Marty McFly in the film Back To the Future), he gained a reputation for meanness. This trait manifested itself when it came to paying backing musicians and giving fans value for money. His parsimony may have stemmed from being short-changed by promoters while touring during the Fifties.

Don Arden, who later managed The Small Faces and was accused of not paying them what they were owed, had promoted Berry’s early UK tours. In his 1998 autobiography All the Rage, the band’s keyboard player, Ian McLagan, observed: “To this day Chuck Berry demands all of his tour money in cash, in dollars, before he sets foot on English soil.” He added sarcastically: “It must be a coincidence.”

When, in 1969, a Fifties rock and roll Revival show took place at Madison Square Garden, featuring Bill Haley, The Coasters and Sha-Na-Na, Rolling Stone’s reviewer painted a depressing picture of Berry’s attitude.

“(He) had already returned to the New York rock scene two years ago,” wrote Jan Hodenfield. “Tired then, he is exhausted now. But, like a jiggling puppet with bills to pay, he gives what he has left.

“His desperation asserted itself when he interpreted a signal from the wings as a sign that he was being hooked from the stage. A sympathetic audience pulled him back on … But sourness was in the air."

In 1972 Berry achieved his only British and American No 1 with “My Ding-A-Ling”. Ironically, it was not one of his own clever observations on the lives of teenagers, welding rhythm and imagery to melody, but a slow-paced cover of a 1952 novelty song, recorded “live” at Coventry’s Locarno Ballroom.

The single’s sexual innuendo prompted morality campaigner Mary Whitehouse to call, unsuccessfully, for the BBC to ban it. The song reached a new generation in The Simpsons when a pupil attempted it during a school talent show. Principal Skinner, like a villain from “School Days”, hauled him off-stage, declaring: “This act is over.”

Berry showed no inclination to accept that his days as an entertainer were over. In 2008, aged 82, he completed a European tour, and he recovered sufficiently after collapsing from exhaustion during a Chicago show on New Year’s Day 2011 to continue a regular gig at a St Louis music-bar. The music legend chose his 90th birthday in October 2016 to announce the release of a new album Chuck, his first album for 38 years.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks