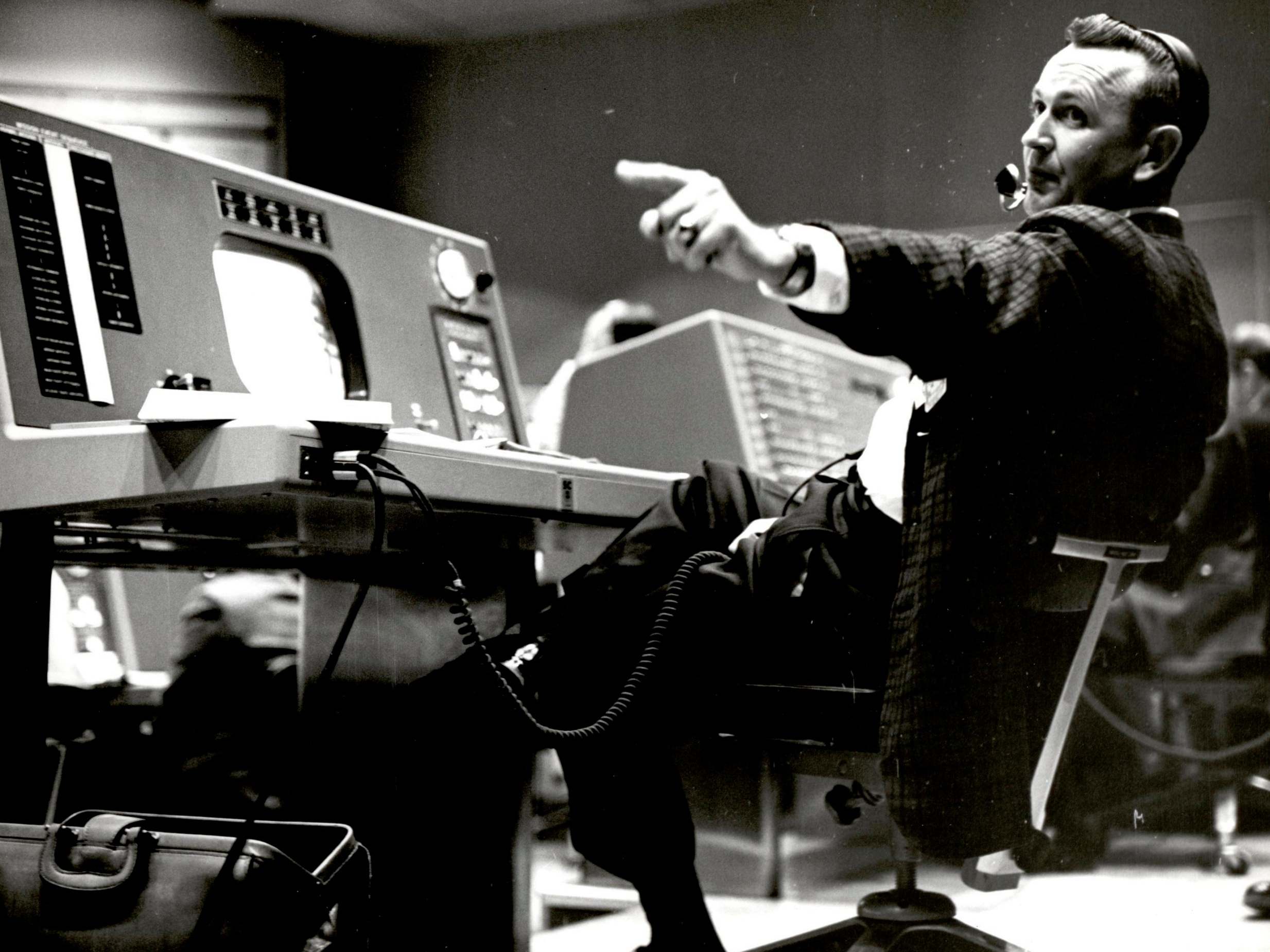

Chris Kraft: Nasa’s first flight director and godfather of Mission Control

He oversaw the infancy and development of the US’s piloted missions into space and was omnipresent during the agency’s 1960s heyday

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Chris Kraft helped to shape the success of Nasa’s piloted space missions in the 1960s as the godfather of the ground-based Mission Control organisation. Although never a household name, he played a crucial role in the achievements of John Glenn, Neil Armstrong and other space pioneers as a backstage visionary during the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo space missions.

Kraft – who has died aged 95 – devised, implemented and managed Nasa’s earliest efforts to usher astronauts into space and to bring them safely – if not always uneventfully – back to Earth.

Long based at what is now the Johnson Space Centre in Houston, Texas, Kraft provided an exacting and, at times, intimidating management style that proved exceptionally effective during the infancy of piloted space flight. He granted wonky, Earthbound number-crunchers power over celebrated astronauts and space agency chieftains. When Gemini 4 astronaut Ed White lingered during the first US spacewalk in 1965, enjoying the scenery, Kraft commandeered the communications system and ordered him to get back in the ship.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Kraft led the team that created Mission Control. He plunged into the minutiae, devising the first space flight plans, designing a communications and tracking system to monitor the astronauts and their health, and pondering what systems and signals they would need on board. He came to believe that most of the work of guiding humans in space would happen on Earth.

Kraft served as flight director for all six Mercury missions and several Gemini flights. He made the final call when American astronauts were “go” and shouldered the burden that even the smallest misstep might bring peril.

In 1967, Kraft listened at a communications console, helpless, when a deadly launchpad fire killed Apollo 1 astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee. In the wake of the tragedy, Kraft and his team improved spacecraft design by fixing faulty wiring and allowing astronauts easier escape if needed, among other changes.

Barely a year later, Kraft helped persuade Nasa leaders to attempt a daring moon orbit, ahead of schedule, for the Apollo 8 mission. Astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and Bill Anders would be the first to fly atop a powerful Saturn V rocket, the first to escape Earth’s gravity, the first to encounter and escape the moon’s gravity, and the first to see the dark side of the moon. The mission proved wildly successful, with the crew orbiting the moon on Christmas Eve and reading from Genesis on a widely viewed television broadcast from space.

Kraft was in the control room when controllers he had trained eased Apollo 11’s Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin onto the surface of the moon on 20 July 1969. The following year, when an oxygen tank exploded on Apollo 13 as it flew towards the moon, Kraft kept in close contact with flight director Gene Kranz, keeping tabs on Mission Control’s efforts to bring the hobbled spacecraft back to Earth and communicating with administrators and the public.

Christopher Columbus Kraft Jr was born in Phoebus, Virginia, now part of the city of Hampton, in 1924. His German immigrant grandparents had bestowed the ocean-crossing explorer’s name on his father because he was born in New York City on the dedication day for Columbus Circle in 1892.

Kraft’s father, a Veterans Administration finance officer, struggled with mental illness and was periodically hospitalised. Kraft’s mother worked as a nurse. They raised their only child in a house next to the town dump.

As a youngster, he sometimes got into fights but was also a high achiever who loved baseball and bugle corps. He enrolled at Virginia Tech in 1942. A childhood right-hand injury – he was accidentally burned in a fire – prevented him from enlisting in the navy during the Second World War. He concentrated instead on baseball and on his studies in aeronautical engineering, a new discipline at the school.

After graduating in December 1944 on an accelerated wartime schedule, he went to work at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (Naca) flight research division in Langley, Virginia. Naca became Nasa in 1958.

Kraft retired from Nasa in 1982 after a decade as director of the Johnson Space Centre. He remained in Houston, working as a consultant for the industry and, in 1994 and 1995, leading a Nasa review team that recommended handing space shuttle operations over to a private contractor.

In the latter part of his life, Kraft appeared in documentary films and offered public commentary on the space programme. He continued to advocate piloted space flights long after the Apollo missions ended and when Nasa seemed happy to focus innovation on robotic landers.

“Any argument for dropping or curtailing manned space flight is fallacious,” he wrote in his 2001 autobiography, Flight: My Life in Mission Control. “This nation can find no better investment in the health, safety, security, education and overall wellbeing of the American public than for a visionary president to declare that Americans will land on Mars. And then make it happen.”

In 2011, Nasa renamed the centre’s historic mission control building the Christopher C Kraft Jr Mission Control Centre.

He is survived by his wife Betty and two children.

Chris Kraft, aeronautical engineer, born 28 February 1924, died 22 July 2019

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments