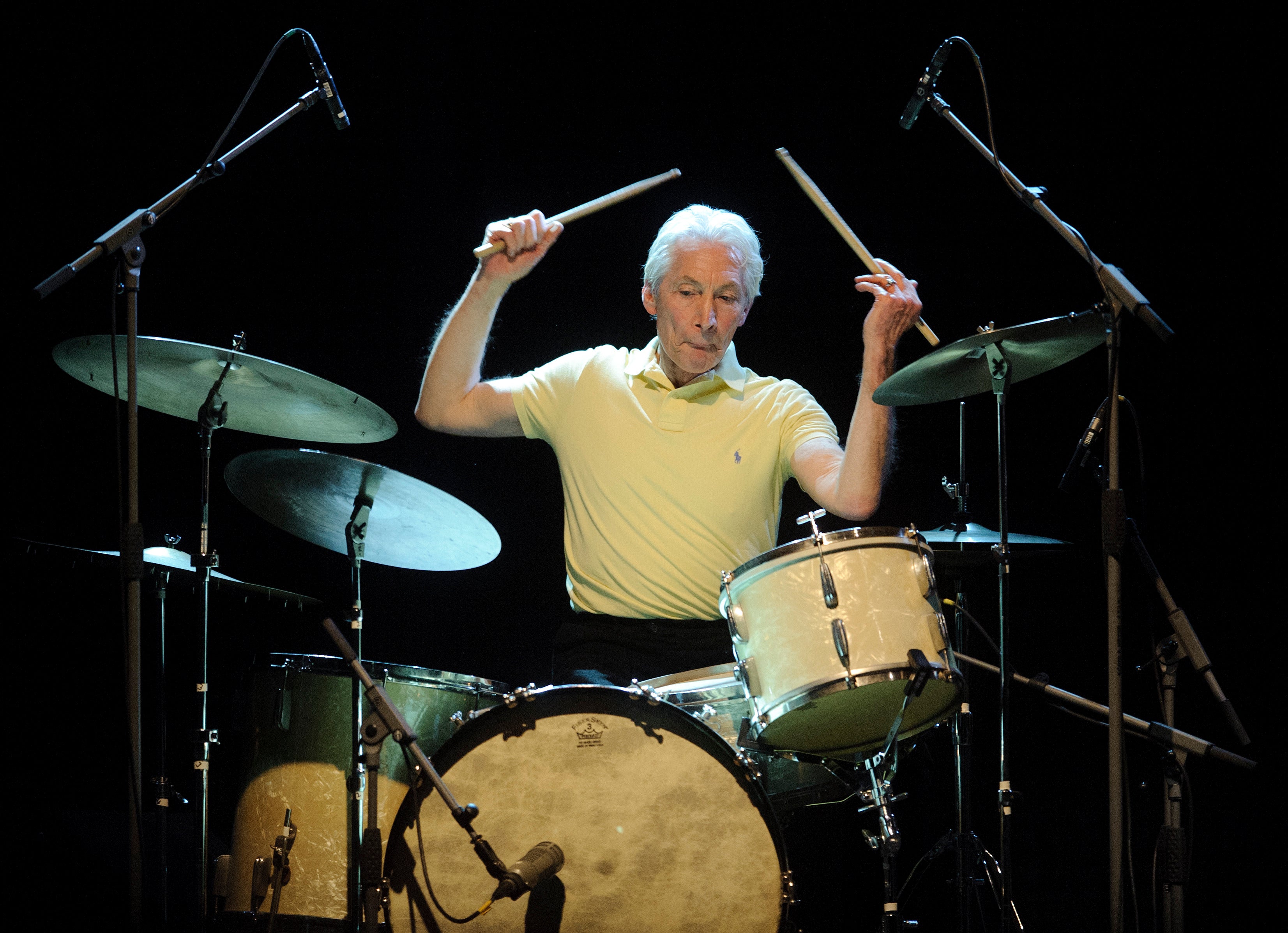

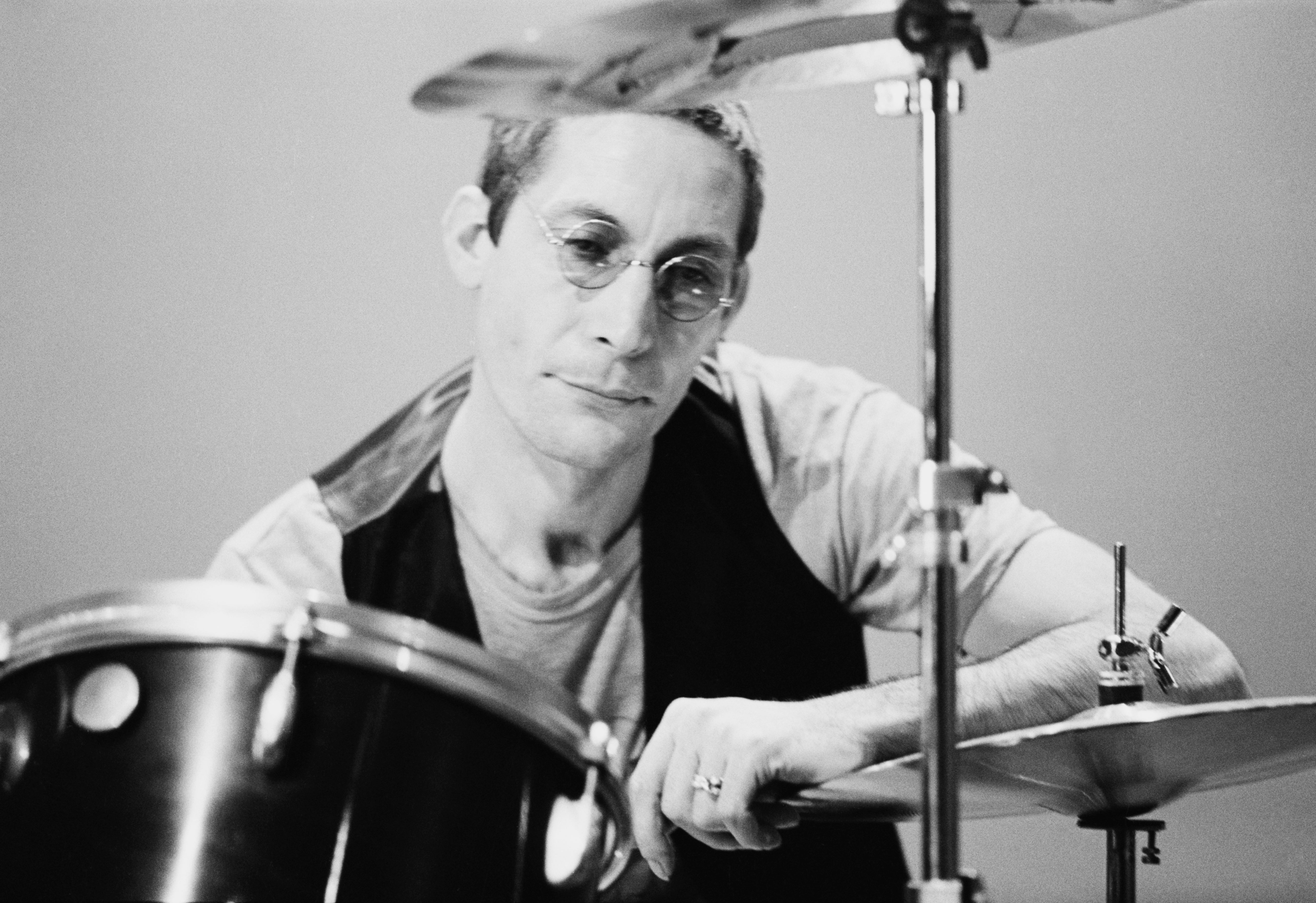

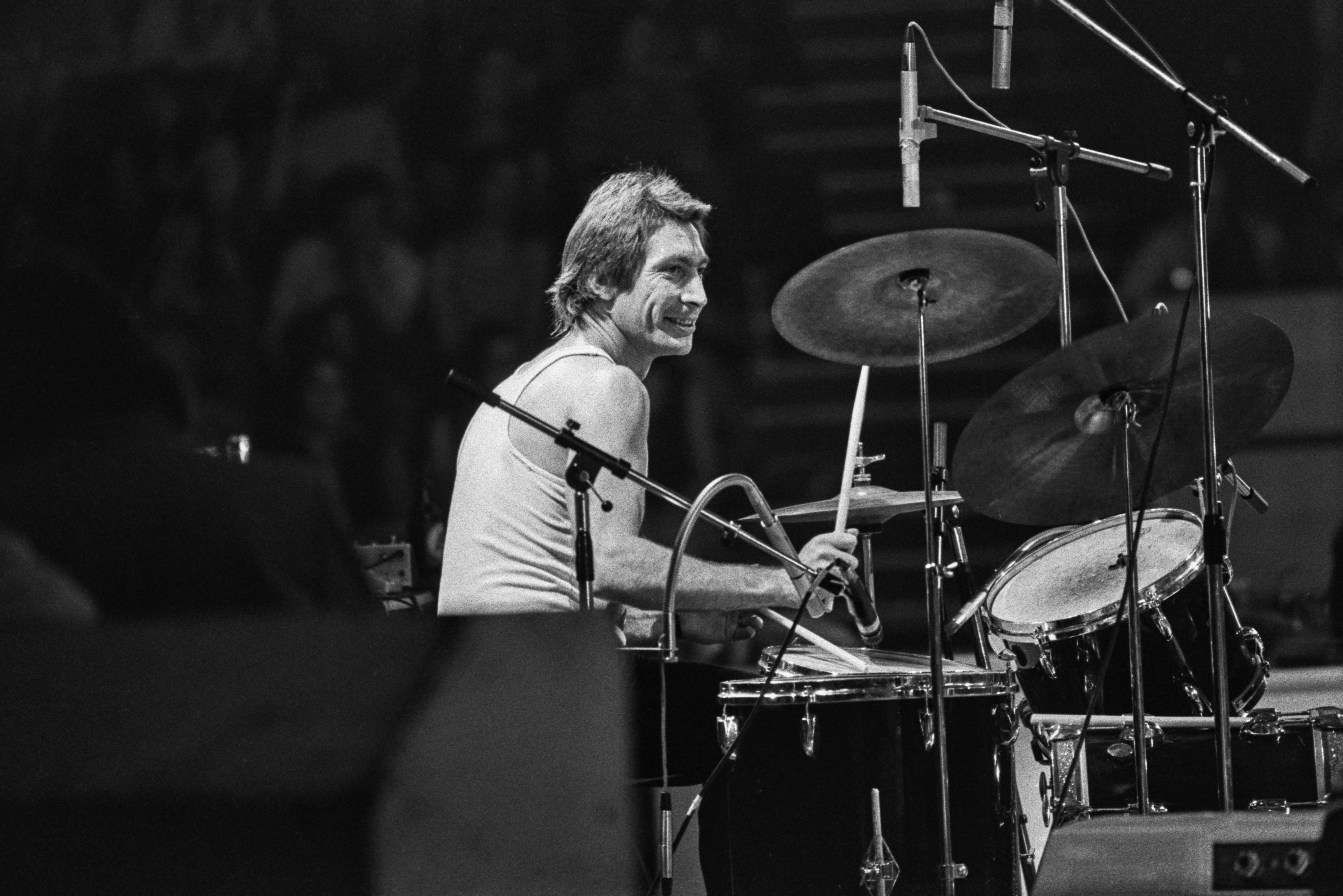

Charlie Watts: Legendary drummer and solid rock of the Rolling Stones

A graphic designer working in an advertising agency when he first met Jagger, Richards and co in 1962, the always dapper jazz fanatic never really wanted to be part of the world’s biggest rock’n’roll band

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Perhaps the most startling revelation ever about the effortlessly dapper Charlie Watts emerged in the late 1980s when news broke that the Rolling Stones drummer, that most avuncular and seemingly solid group member, had for years dabbled with heroin and had considered himself an alcoholic.

Almost as surprising was the disclosure that in the middle of the night at an Amsterdam hotel, a drunken Mick Jagger phoned Charlie Watts’s room: “Is that my drummer boy? Why don’t you get your arse down here?” “Charlie shaved,” said Keith Richards, “put on a suit and tie, came down, grabbed him and went BOOM! Charlie dished him a walloping right hook. He landed in a plateful of smoked salmon and slid along the table towards the window. I pulled his leg and saved him from going out into the canal below.”

It’s now part of rock’n’roll folklore that Jagger was issued the warning: “Don’t ever call me your drummer again. You’re my f****** singer!”

Avowedly faithful to his wife Shirley in a band of compulsive philanderers, the man whose only on-the-road recreational activity appeared to be the sketches he would draw of every single hotel room in which he stayed, clearly had another side to him.

Somewhat willfully eccentric, never really wanting to be in or enjoying the Rolling Stones, to whose music he never listened, on tour in constant hope of catching the next plane home, the drummer’s countenance was one of a perpetual gentle glumness and ironic resignation. But there was a suggestion that all along such an existentialist pose carried an element of studied affectation: Watts, who always considered himself a jazz rather than R’n’B drummer, had been the first Stone to regularly smoke marijuana, at first hiding this from the other group members, aware such youngsters would be shocked. And with Jagger and Richards, he had been tough enough to last the course in a group with its share of casualties.

Older by a couple of years than those other two survivors, Watts was working as a graphic designer in a prestigious advertising agency when they first met him. He was definitively a modernist. “We all thought Charlie was very kind of hip, because of his jackets and shirts,” said Jagger. “Because he was working in an advertising agency, he was very different. It was good for the band to have someone who was sort of sharp … We had the advantage that Keith and I both get along very well with Charlie. The fact that there’s three of us who get along so well is very important.”

Watts’s father worked for British Railways as a parcel deliveryman; his mother had been a factory worker. He had a sister, Linda. The family lived in Kingsbury, northwest London, in a modest but fastidiously tidy house: his father would make him cover all his books in brown paper – “even my Buffalo Bill album”.

To me, how an American plays the drums is how you should play the drums. That’s how I play. I mean, I play regular snare drum, I don’t play tympani style, although I know guys who play fantastically like that. I play march-drum style

Watts was brought up, he remembered, running to the air-raid shelter. From an early age his ability at art was evident. And his mother would recall her son rapping out tunes on the kitchen table with his knife and fork. In 1955, when he was 14, he bought a banjo but couldn’t make head or tail of how to play it. Then he made a stand for the instrument “and hit the round skin part with brushes; it was a like a drum anyway”.

That Christmas his parents bought him his first drum kit, which cost £12. Charlie practiced at home all the time, playing along to jazz records, which, apart from bespoke suits, was his great love. “Gradually, I built up my confidence.”

Watts’s drumming influences included Britain’s Phil Seamen, but he believed bebop icon Kenny Clarke to be the world’s best sticksman. “To me, how an American plays the drums is how you should play the drums,” he said years later. “That’s how I play. I mean, I play regular snare drum, I don’t play tympani style, although I know guys who play fantastically like that. I play march-drum style. Most rock drummers play like Ringo; a bastard version of tympani style. In reality, that’s what it is because tympani style is fingers and most rock drummers play like that because it’s heavy offbeat.”

Leaving school at 16 in July 1957, two months later he began studying at Harrow School of Art. In the summer of 1960 he began work at Charles Hobson and Gray on Regent Street, a prestigious agency, starting off as a £2-a-week teaboy but soon progressing to be a graphic designer.

Jazz remained his principal interest. So awed was he by the work of the great saxophonist Charlie “Bird” Parker, legendary for his use of heroin, that during this period he wrote a book about him, Ode to a Highflying Bird: “It was a kid’s book, with a bird character instead of Charlie Parker.” It was published in 1965. The Rolling Stones’ 1967 album Between the Buttons featured six cartoon drawings by their drummer on the back cover.

At a show Watts played at the Troubador in Earls Court, he met Alexis Korner, doyen of British blues. In late summer 1961, Korner asked the drummer to join his group Blues Incorporated, but he declined. When the offer was repeated the following January, he agreed. Joint leader of the band with Korner was Cyril Davies, with Jack Bruce on bass. “On a good night it was amazing, a cross between R’n’B and Charlie Mingus, which was what Alexis wanted,” Watts recalled.

In the audience at a Blues Incorporated gig Charlie noticed Shirley Ann Shepherd, who was studying sculpture at the Royal College of Art: they married in 1964.

Concerned that too many late nights was affecting his day job, Watts had quit playing with Blues Incorporated, replaced by Ginger Baker, when the newly born Rolling Stones approached him. He was not immediately convinced, but Korner persuaded him that they had potential longevity. Moreover, they all seemed to get on with each other, Charlie especially with Mick and Keith. And group founder Brian Jones warmed to Charlie’s commitment and idealism. “With Charlie,” said Ian Stewart, the group’s keyboard player, in 1979, “we were thinking about the atmosphere in the band. In the early days I thought Keith might be an awkward person to get to know. I’d watch Keith with other people, and he always seemed to back away a bit. But he and Charlie were a f*****’ comedy team. They had a dual sense of humour.”

“Charlie is incredibly honest, brutally honest,” said Richards. “Lying bores him. He just sees right through you to start with. And he’s not even that interested in knowing, he just does. That’s Charlie Watts. He just knows you immediately. If he likes you, he’ll tell you things, give you things, and you’ll leave feeling like you’ve been talking to Jesus Christ…The only word I can use for Charlie is deep.”

In the first official Rolling Stones fan club letter, Watts’s biography included the claim that his ambition was “to own a pink Cadillac”. (In fact, he never learned to drive, but in 1983 bought a 1930s Lagonda, which he would sit in and look at.)

By then Lillian Watts, his mother, was having to wash the 14 shirts that Charlie quickly acquired, his first symbols of success. “He’s always been a good boy. Never had any police knocking on the door or anything like that. And he’s always been terribly kind to old people. He was always a neat dresser. That’s why I get perturbed when they call them ugly and dirty. When he’s home you can’t get him out of the bathroom. People think he’s moody. But he’s not really. He’s just quiet. He hates fuss and gossip.”

In 1967 Charlie and Shirley moved to a substantial property in Lewes in East Sussex. By the early 1970s they had moved again, to north Devon, to an even more impressive home, a 600-acre stud farm where they bred Arabian horses. Specialising in horses of Polish origin, the business eventually was worth more than £10m – even though in 2000 the farm manager was imprisoned for false accounting.

The perpetual squabbling between the group’s two central protagonists during the Seventies and Eighties inclined the drummer to quit the Stones. But instead he aired his frustrations through a series of side projects. In the late Seventies Watts started playing drums in Rocket 88, Ian Stewart’s boogie-woogie group; in the Eighties he toured across the globe with a line-up including Jack Bruce, Courtney Pine, and Evan Parker; Warm and Tender, by the Charlie Watts Quintet, was released in 1993, following it with Long Ago and Far Away three years later. He also released an album with Jim Keltner, and with The Charlie Watts Tentet released Watts at Scotts. And from 2009 onwards he played concerts with another group he put together, the ABC&D of Boogie Woogie.

Diagnosed with throat cancer in 2004, he underwent a course of radiotherapy, and recovered, returning to his day job with the Stones.

His work with the group had earnt Watts an estimated £70m. As befitted such an aesthete, he spent a portion of his time and money seeking out appropriate rare artefacts. These included one of Kenny Clarke’s drum kits, as well as one once played by Big Sid Catlett – “one of the great Thirties swing drummers”. He also collected signed first editions of 20th-century writers: “Agatha Christie: I’ve got every book she wrote in paperback. Graham Greene, I have all of them. Evelyn Waugh, he’s another one. Wodehouse: everything he wrote.”

Musing on his more than fifty years with the Rolling Stones, Watts reflected: “You have to be a good drummer to play with the Stones, and I try to be as good as I can. It’s terribly simple what I do, actually. It’s what I like, the way I like it. I’m not a paradiddle man. I play songs. It’s not technical, it’s emotional. One of the hardest things of all is to get that feeling across.”

Charles Robert Watts, drummer: born London, 2 June 1941; married 1964 to Shirley Ann Watts (one daughter); died 24 August 2021

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments