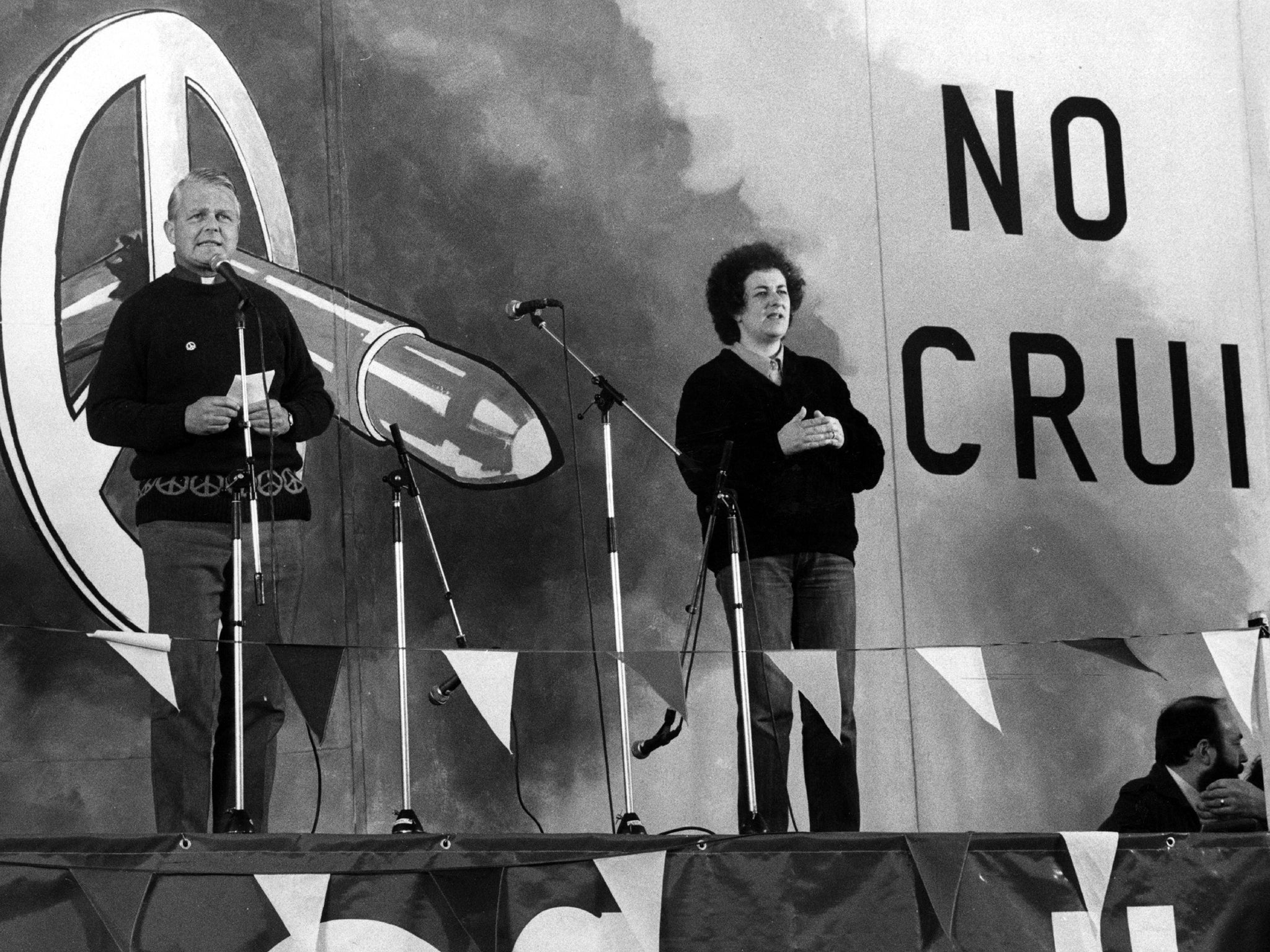

Bruce Kent: Priest and anti-nuclear peace activist

Catholic priest who held various positions with the pressure group and remained convinced that war was the biggest cause of poverty on the planet

Bruce Kent, who has died aged 92, was for decades one of the brightest stars in the Catholic firmament in Britain, helping the church out of a period of stifling and self-regarding clericalism and towards a concern for global problems, notably the threat posed by nuclear weapons.

Kent was born in Blackheath in 1929, the second of three children to Kenneth, a Canadian Presbyterian businessman, and his Catholic wife Mollie.

In 1940 his mother and the three children went to Canada for safety, returning in 1943. Bruce and his brother were sent to Stonyhurst, the Jesuit-run public school in Lancashire. He very slowly came to love a place where the ethos was piety and the rule was flogging. In October 1947 he started his two years of national service during which he was commissioned in the Royal Tank Regiment. During that time his interest in ordination was awakened by the powerful Jesuit preacher Father Joseph Christie. Kent realised that “the best way I could live my life and bring truth to the world and good news to the poor was to become a priest”.

He had, however, been accepted by Brasenose College and started what he called his three Oxford “lotus-eating years”, where he divided his attentions between religion and the University Air Squadron.

In the autumn of 1952, having missed the chance of acceptance at the elite English College, Rome, he settled into St Edmund’s College, Ware, the Westminster diocesan seminary that Pugin had called “the priest factory” and whose dank, gloomy regime Kent found “awful”. “The tedium was considerable”, he later wrote. “No one can suffer four 45-minute lectures in sequence without a numbing of the soul.”

He was ordained in May 1958 by Cardinal Godfrey in Westminster Cathedral and sent as a curate to Our Lady of Victories in Kensington. He enjoyed parish duties, though working with sick children presented him with difficulties. “The hospital certainly taught me that anyone with easy answers to the problem of innocent suffering has no answers at all,” he recalled.

It was in his next post, part-time as a curate in north Kensington and part-time as assistant to the Westminster diocesan financial secretary, that he fell under the influence of Thomas Roberts, the Jesuit who had recently been Archbishop of Bombay.

Having made a success of his jobs, Kent was appointed second, then principal, secretary to the new Archbishop of Westminster, John Heenan, whose kindness and industry he admired and whose politics and lack of enthusiasm for ecumenism he rejected. He accompanied his superior to the Second Vatican Council in 1964 and continued with him to India, returning, despite Heenan’s passionate hatred of communism and communists, via Moscow.

In Easter 1964, when the cardinal’s chauffeur was held up by a CND demonstration in Trafalgar Square, Kent asked Heenan what he thought about the bomb.

“Better dead than red” was the Cardinal’s laconic reply. Kent did not last much longer, though he was made a monsignor. He recounts how he took some pride in the fact that his new rank allowed him to wear a purple shirt, until Tom Driberg MP came up to him at a Fleet Street party, tickled the monsignorial chest and said: “Who’s this, then? Robin Redbreast?”

In 1966 he started an eight-year stint as chaplain to the far-flung and varied components of London University. (Wye College in Kent he found was nearer Calais than London.) His time there was taken up with establishing a place of welcome at the Gower Street chaplaincy, showing students the life of those sleeping rough and, on one occasion, protecting a woman student from the sexual advances of a priapic Italian bishop.

His activities at Gower Street and his increasing attraction towards disarmament stirred up the open hostility of Heenan. In the months before his death in 1975, the cardinal publicly and privately poured scorn on what he called his naive embrace of the Catholic peace organisation Pax Christi, on whose international executive Kent served under the chairmanship of Cardinal Bernard Alfrink of Utrecht.

Feeling burnt out and in what he termed “a semi-contained nervous breakdown”, Kent accepted a move from the chaplaincy in 1974 and became ever more active on peace and other ethical issues with CND and War on Want, helping to establish the Campaign Against the Arms Trade.

His pieces in the Catholic Herald newspaper poked fun at the people and institutions he referred to as St Bingo, and its parish priest, Canon McGroggin, was “particularly good at neutering parish councils, pouring water over charismatic revival and seeing off ecumenical stirrings”. St Bingminister was the double he created for Westminster Cathedral; and there was the Neo-Coptic Patriarch Mars Bar II and Canoness Gladys McEverite. She was apt to say things like “if Our Lady had wanted male priests she would surely have made such an extraordinary wish clear from the very beginning”.

In 1977, the year Kent assumed the chairmanship of CND, Heenan’s successor at Westminster, the Benedictine monk Basil Hume, gave him the needy but happy parish of St Aloysius beside Euston Station. The job strengthened his antipathy toward the secretive and elitist right-wing Opus Dei organisation and what he called its “rigid moral theology and sexual hangups”.

He later expressed incredulity at Vatican plans for the rapid canonisation of its Spanish founder, the Marquis of Peralta, Jose Maria Escriva. Kent combined looking after the parish with a flood of demands from his non-parish interests. In 1979 he asked Hume’s permission to relinquish the parish and take the full-time (and high-profile) job of CND general secretary. The cardinal agreed but, Kent believed, lived to regret it. He ran CND until 1985, when he became its vice-chairman.

The 1983 election called by Margaret Thatcher signalled a determined attack on a rapidly strengthening CND, led by the Murdoch press, Michael Heseltine, the Ministry of Defence and a body called Policy Research Associates, which included Lord Chalfont, Norris McWhirter and Julian Lewis. During that attack, Kent felt he had been traduced by Hume in the latter’s correspondence with Lewis. In his biography of Hume, Anthony Howard quoted Kent’s words to the cardinal: “It cannot be right for a bishop to discuss his priests in this way with strangers.”

He was increasingly disenchanted with church attitudes. In his words, “support for Solidarnosc in Poland was priestly. Support for the Sandinistas in Nicaragua was not. To be bishop of HM Forces was not political. To be CND chairman was.” In December 1986, Kent sought Hume’s permission to retire from the active priesthood. In 1988, without any formal ecclesiastical dispensation, he married Valerie Flessati, a pillar of Pax Christi, in Camden Town Hall.

In 1992 he unsuccessfully stood for the Labour Party in Oxford West. His last contact with Hume – one of friendship and mutual respect – came in 1999. In reply to Kent’s hand-delivered note two days before his death, the cardinal wrote: “I have received a great many letters, but none gave me more pleasure than yours.”

Kent continued talking as passionately as ever about peace, reminding his listeners at a meeting in Swindon in February 2005, for instance, that war and the preparation for war were the single biggest causes of poverty in the world. “We must make the connection in people’s minds between war and poverty, and get that huge military budget spent on solving all the real problems in the world,” he argued.

To his death he hewed to the view he often expressed: “One day it’s going to dawn on the human race that war is as barbaric a means of resolving conflict as cannibalism is as a means of coping with diet deficiencies.”

Bruce Kent, Roman Catholic priest and activist, born 22 June 1929, died 8 June 2022

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks