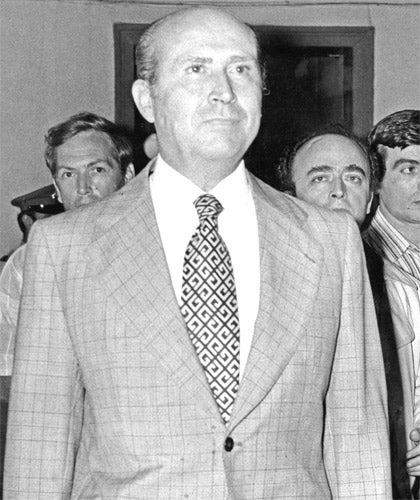

Brigadier General Dimitrios Ioannidis: Soldier who served life imprisonment after leading coups in Greece and Cyprus

Nicknamed "the Invisible Dictator" by his fellow Greeks, Brigadier General Dimitrios Ioannidis took part in two infamous military coups in his own country and masterminded another in Cyprus, the latter sparking Turkey's invasion and the ongoing partition of the Mediterranean holiday island. Ioannidis, who died unrepentant after serving 35 years of a life sentence for treason, also commanded Greece's notorious military police, ESA, which instilled fear and inflicted widespread torture on dissidents during the late 1960s and early '70s.

He was a 44-year-old Lieutenant-Colonel in 1967 when two full colonels and a brigadier asked him to join them in a coup d'état they said was to suppress the rising danger of communism. The plotters, led by Colonel George Papadopoulos, took control on 21 April 1967. The US government denied involvement in the coup – most historic documents suggest they were not informed in advance – but US protestations about "the rape of democracy" were short-lived against the backdrop of an anti-communist bulwark in the region.

In reward for his support during the coup, Papadopoulos promptly appointed Ioannidis as head of ESA (an acronym from the Greek for military police), which he proceeded to turn into something of an army-within-an-army, feared not only by civilians but also by army officers and soldiers wary of being branded communist or even "centrist." Once Papadopoulos had declared martial law, ESA effectively became the justice system in what had long liked to call itself "the world's oldest democracy." The oldest it may have been, but Ioannidis and his cronies saw fit to interrupt it for seven years, setting Greece back for at least a generation within the world community and economy.

During those years ESA became the Greek equivalent of the Shah of Iran's dreaded Savak secret service, jailing, torturing and/or exiling thousands, probably tens of thousands, of dissidents (ESA usually kept it simple by calling them communists). Among the victims was the renowned actress and singer Melina Mercouri, who was stripped of her citizenship and exiled, defiantly proclaiming, "I was born a Greek and I will die a Greek." (She did die, in 1994, after serving as Minister for Culture in the post-military democracy). Ioannidis' "successes" brought him the rank of full colonel in 1970 and Brigadier General in 1973.

It was 17 November 1973, now a famous date in the modern Greek calendar, that would hasten the end of the junta. Papadopoulos had initiated a degree of liberalisation, releasing some political prisoners and easing censorship. Students based in Athens Polytechnic had been striking and protesting against military rule for three days, broadcasting from a makeshift radio station and calling themselves "the Free Besieged." On the 17 November, Ioannidis sent a tank crashing through the Polytechnic gates and launched a new crackdown.

Eight days later, Ioannidis, believing Papadopoulos's liberalisation was dangerous and unpatriotic, launched a new military coup along with some younger officers and overthrew the old junta. Ioannidis personally installed a new president and prime minister but it was clear he had become the "Invisible Dictator." Time magazine described him at the time as "a rigid, puritanical xenophobe – he has never been outside Greece or Cyprus – who might try to turn Greece into a European equivalent of Muammar Gaddafi's Libya."

Just as he had during the previous junta, Ioannidis remained a spectral figure. In Athens, where people like to say, even though it's a capital city, that "everybody knows everybody else," Ioannidis, or photographs of him, were virtually never seen. The effects of his rule were highly visible, however, with junior officers acting as watchdogs to keep an eye on their superiors in case of dissent.

His "invisible" rule would last only eight months. Cyprus, with a majority ethnic Greek population but a historic Turkish minority, had been granted independence by Britain in 1960. Ioannidis, insisting that the island should be united with Greece, masterminded a military coup by Greek officers against the ethnic Greek Cypriot president Archbishop Makarios on 15 July 1974. It was a disastrous decision that still blights the potentially-paradise island today, 36 years on.

On 20 July, the Turkish Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit sent paratroopers into northern Cyprus "to protect ethnic Turks" even though many ethnic Greeks lived and largely ran much of the north, including the tourist resorts Kyrenia and Famagusta. The ethnic Greeks fled to the south, abandoning their homes and businesses. Despite three and a half decades of would-be diplomacy, the island remains split – largely Ioannidis's legacy. His junta collapsed soon after the Turkish invasion and he was arrested in January 1975, convicted of high treason and sentenced to death, a sentence to which he responded with a wry smile in court. It was immediately commuted to life imprisonment in the notorious Korydallos prison, west of Athens, built by the colonels to detain opponents.

Dimitrios Ioannidis was born in Athens to a poor family who had moved from Epirus in the mountainous north-western corner of Greece. He joined the Greek military academy as a cadet in 1940, just before Italy invaded Greece, and fought against both Italians and Germans. In peacetime, he served for a time as a Greek officer in Cyprus, where he established his belief that the island should be united with the mainland government in Athens.

Of the three leading members of the 1967 coup, Colonel George Papadopoulos died of cancer in hospital, still a prisoner, in 1999; Nikolaos Makarezos was released to house arrest on health grounds in 1990 and died last year. Stylianos Pattakos was given total freedom in 1990 on humanitarian grounds because of "imminent danger to his health." He is still alive 20 years on.

Like Papadopoulos, Ioannidis refused to repent during his 35-year incarceration and refused to ask for clemency, claiming he had acted as a patriot. To some older Greeks, he remained something of a hero. He died of respiratory problems after being moved from Korydallos prison to hospital. He was never married.

Dimitrios Ioannidis, soldier and politician: born Athens 13 March 1923; died Athens 16 August 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks