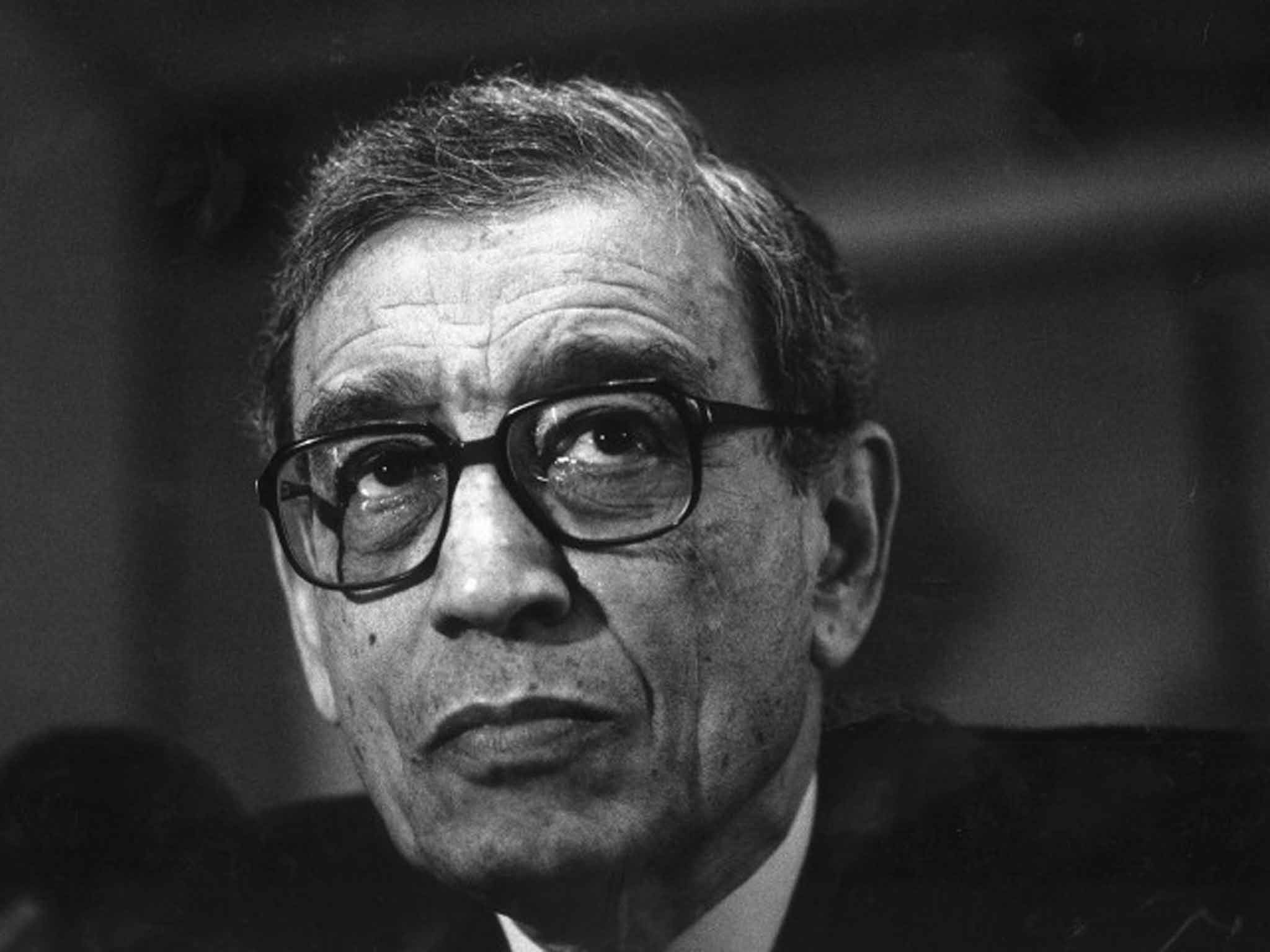

Boutros Boutros-Ghali: UN Secretary-General whose tenure was tainted by his response to crises in Rwanda and Bosnia

His view that a bureaucracy was best run by stealth and sudden violence did not endear him to his colleagues

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.No Secretary-General ever took the helm of the UN at a more propitious time than the Egyptian diplomat and politician Dr. Boutros Boutros-Ghali.

In January 1992, when he became the sixth to hold the post, the Security Council had held its first meeting at summit level – a meeting billed as an unprecedented recommitment to the purposes and principles of the UN charter. The Cold War was over and the Security Council was unified at last, a situation that presented a number of opportunities. For years, the Secretary-General had been obliged to act in the face of Council paralysis and ill will. Boutros-Ghali had said that if he had been offered the job five years before, he would have turned it down. “The UN then was a dead horse, but after the end of the Cold War, the UN has a special position,” he said.

Boutros-Ghali believed that it was time to shift the UN's emphasis from world development to human rights. He wanted an expansion of UN peacekeeping – and for the UN to become involved in national reconciliation processes, the restructuring and rehabilitation of governments and the creation of democracy. Some UN colleagues were sceptical of this vision of global leadership and thought that he should have pursued a role complementary to that of the Security Council, instead of trying to compete with it.

Of the five permanent members in the Security Council, only France had actively supported his candidacy. In the autumn of 1991, America had abstained on the vote. President George Bush had wanted Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan to become the next Secretary-General. But Boutros-Ghali was a personal friend of the then President of France, François Mitterrand. Boutros-Ghali had facilitated Egyptian entry into Francophonie, the worldwide association of nations that share the French language – and an organisation allowing France to pursue its interests via a cultural and linguistic crusade.

For public consumption, Boutros-Ghali, then 68, would be portrayed as the first African Secretary-General – a neutral, a man of the Third World, an African-Arab, and a Coptic Christian married to an Egyptian Jew, and a man who spoke flawless French.

Boutros-Ghali was born into the Egyptian aristocracy. His great-grandfather managed the Egyptian royal family's wealth; his grandfather was appointed Prime Minister in 1908 and was assassinated by a fundamentalist two years later, apparently because he cooperated with the country's British overlords.

Boutros-Ghali was a French-educated intellectual and scholar. He studied at the Sorbonne in Paris, from where, in 1949, he received a doctorate in international law. At the time he was considered to be an ardent anti-colonialist. He became a professor of international law and international relations at Cairo University, a Fulbright Research scholar at Columbia University and director of the research centre at The Hague Academy of International Law.

In 1977 he was invited to join the Egyptian government by President Anwar Sadat and was one of the few Egyptian officials to accompany Sadat on his historic trip to Jerusalem in 1977. Boutros-Ghali attended the Camp David summit conference in September 1978 and he had a role in negotiating the 1979 Camp David Accords between Egypt and Israel.

After the assassination of Sadat in 1981, Boutros-Ghali transferred his loyalty to his successor, Hosni Mubarak, and he was appointed a Minister of State for foreign affairs. As a member of the country's influential Coptic Christian minority, Boutros-Ghali could go no higher given the hostility of Egypt's Islamic fundamentalist lobby. In 1991, the year in which he was lobbying to become UN Secretary-General, Mubarak appointed Boutros-Ghali Deputy Prime Minister for International Affairs.

Boutros-Ghali became a member of the Egyptian Parliament in 1987 and was part of the secretariat of the National Democratic Party from 1980. Until assuming the office of Secretary-General of the UN, he was also vice-president of the Socialist International. He was a member of the International Law Commission from 1979 until 1991.

Boutros-Ghali began his campaign to become the Secretary General in 1991 with a tour of Africa. It was familiar territory. As the president of Egypt's Society of African Studies, he had known African leaders for 15 years and had created a special fund for cooperation in Africa with a budget of millions of Egyptian pounds under his direction. This had enabled him to send hundreds of Egyptian experts to African countries.

Even so, there was an undercurrent of resentment among some diplomats from sub-Saharan African countries when he started his UN campaign. Boutros-Ghali was the only light-skinned Arab-African on the list of African candidates and he lacked the wholehearted support of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), which failed to make a choice among seven other African candidates.

In the Security Council there was the added complication of the rivalry between France and Britain over which region on the African continent, whether Francophone or Anglophone, should provide the candidate. Four of the seven African candidates for the job were from English-speaking Africa. In November 1991, when the votes were counted, British diplomats found it hard to conceal their disappointment, for they were anticipating an inconclusive result.

In spite of the auspicious beginning, Boutros-Ghali went on to preside over one of the most turbulent periods in UN history. During his five-year term, the UN stumbled from one crisis to another. The three great tragedies of the former Yugoslavia, Somalia and Rwanda proved how ill-equipped the UN was to handle the tasks that were heaped upon it by the Security Council and by an ambitious Secretary-General.

The UN was plagued by an ongoing financial crisis. A year into his first term, the UN had 70,000 soldiers throughout the world, with the majority in Europe. But the resources for these projects were not made available by member states. The UN mission to former Yugoslavia, the UN Protection Force (UNPROFOR), was the largest and most expensive in UN history, and saw its peacekeepers marooned in the midst of war and its mandates plagued by ambiguities.

Boutros-Ghali became increasingly unpopular in the US State Department and a story did the rounds that then US Ambassador, Madeleine Albright, was appalled when he kissed her hand. A turning point in the US attitude to Boutros-Ghali was more likely to have occurred in October 1993, after a botched operation by the US military in Somalia, when 18 US elite forces were killed attempting to arrest a warlord, an arrest mandated by the Security Council and enthusiastically endorsed by Boutros-Ghali. The US blamed Boutros-Ghali and the UN for what had happened – and there was no further appetite in Washington for UN peacekeeping.

The UN missions created by the Security Council in these years were ill-conceived, short-sighted and proved the organisation not yet mature enough for such responsibilities. Boutros-Ghali's autocratic style did not endear him to experienced UN bureaucrats, either. In a shocking decision he insisted that he alone controlled the crucial access to the Security Council by Secretariat officials; only those with his express permission were to brief the Council.

This created problems, particularly during his extensive tours abroad. In April 1994, as the news from Rwanda worsened, Boutros-Ghali continued a three-week European tour which was considered to be inexplicable and irresponsible. There were complaints from the Security Council that ambassadors were inadequately briefed about events at a time when the genocide of the Tutsi gained momentum throughout the country, and when it might still have been possible to stop it spreading.

The UN's internal enquiry into the genocide concluded diplomatically that Boutros-Ghali “should have done more” to argue the case for reinforcing the peacekeepers in Rwanda and pointed out the role of the Secretary-General was limited if performed by proxy.

Boutros-Ghali considered himself to be an intellectual in politics. For many UN staff he was aloof and he would concede a paternalistic tone as a result of many years of teaching. His view, expressed to the New York Times, that a bureaucracy was best run by stealth and sudden violence did not endear him to his colleagues. In his memoir, a book published in 1999 and entitled Unvanquished: A US-UN Saga, all decision-making is quite clearly his own. In an extraordinarily angry book, Boutros-Ghali blamed all UN failures on the Clinton administration.

The relationship between Boutros-Ghali and the US had soured when, in May 1996, a major row developed over the killing by Israeli forces of Lebanese civilians sheltering at a UN post in Qana in Southern Lebanon. Boutros-Ghali was six months away from selection for a second term, but he chose to publish an objective UN military report on the incident revealing that the Israeli shelling of the compound was unlikely to have been the result of a gross technical or procedural errors. This infuriated the Israelis and the US.

There was a brutal attack upon him by the Clinton administration – and the issue of whether or not he should have a second term was used as a weapon in the 1996 Presidential contest. The Republican contender, Bob Dole, as part of an anti-UN campaign, portrayed Boutros-Ghali as a world commander ordering US troops into battle. The Clinton camp let it be known that unless Boutros-Ghali was replaced, the Republican-controlled Congress would never agree to pay the $1.6bn debt the US owed the world body, and that a more zealous reformer was needed at the UN.

Boutros-Ghali dug in his heels. There was an unseemly and public row that further damaged the UN's reputation. France was determined that Africa be allowed to have a two-term Secretary-General – but a deal was reached which allowed Kofi Annan, from Ghana, then head of the UN's Department of Peacekeeping Operations, to succeed Boutros-Ghali.

Boutros-Ghali had more than 100 publications to his name and numerous articles dealing with regional and international affairs, law and diplomacy. His most widely published work was Agenda for Peace, a series of ideas on the role and functions of the UN. This report was produced in response to a request from the triumphant 1992 Security Council on how to make the UN more relevant.

Central to Agenda for Peace was the proposition, almost as old as the UN itself, to give the organisation its own forces. Boutros-Ghali believed countries needed to keep forces on stand-by ready for UN service, trained and equipped to fight as well as to undertake policing tasks. Agenda for Peace was followed in May 1994 by a report entitled Agenda for Development that set out five foundations for development; these were peace, the economy, the environment, society and democracy.

Boutros-Ghali left UN office at the end of 1996. The following year he was appointed the Secretary General of Francophonie, the association of French-speaking states, and he lived in some splendour in the heart of Paris.

In 2001, the University of Ottawa awarded him an honorary doctorate. From 2003 to 2006, he chaired the board of South Centre, an intergovernmental think tank for developing countries. He supported the Campaign for the Establishment of a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly, a movement to establish citizens' representation at the UN, from its founding in April 2007. From 2009-2015, he was a member of the jury for the Conflict Prevention Prize, awarded every year by the Fondation Chirac.

Boutros Boutros-Ghali, politician: born Cairo, Egypt 14 November 1922; married Maria Leia Nadler; died Cairo 16 February 2016.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments