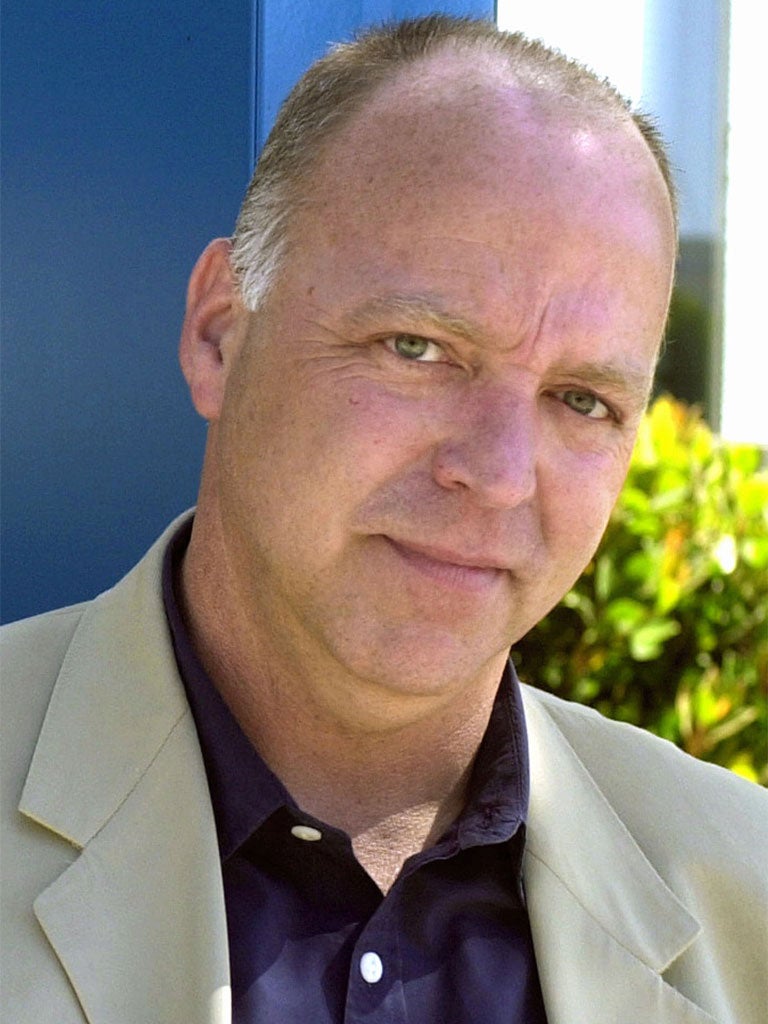

Bingham Ray: Film producer with a maverick streak

Non-Hollywood films need nurturing in America. The producer-distributor Bingham Ray spotted potential hits, brought them to the screen and, with canny marketing, made them commercially and critically successful. He worked with Mike Leigh, David Lynch and Lars von Trier among others, and also helped kick-start American interest in Iranian cinema. Ray's enthusiasm for cinema was huge and infectious, yet unlike some independent producers he strove to bring the film-makers' vision to the screen rather than impose his own.

Ray was introduced to cinema at a young age: his reward for completed homework was to be allowed to watch films. After making a few films at school he studied Theatre Arts and Speech at Simpson College, Iowa. From programmer and manager at the Bleecker Street Cinema in Greenwich Village, he moved through various film companies, and oversaw the release of Gus van Sant's Drugstore Cowboy (1989).

In 1991 he joined distribution veteran Jeff Lipsky to form October Films. Initially working out of Lipsky's garage in Los Angeles, their first hit came that year with Mike Leigh's third film Life is Sweet, and they continued the association through the rest of the decade. October also worked with the British film-makers Shane Meadows and Gilles MacKinnon. The company was soon producing as well and had a share in Gregg Araki's The Living End (1992), a bittersweet road movie about a film critic and a gay hustler, both HIV positive. Commercially unpromising as it might seem, it was very successful.

The years 1992 and '93 saw two French films about music: Alain Corneau's Tous les matins du monde, about the baroque composer Marin Marais, and Un coeur en hiver, about a violinist's love triangle, starring Emmanuelle Béart, Daniel Auteuil and André Dusollier, with a soundtrack featuring Ravel's Violin Sonata. Between them, these films amassed an astonishing $6m US gross. In what might seem a limited-interest genre, the Jacqueline du Pré biopicHilary and Jackie (1998), helped by Oscar nominations for Emily Watson and Rachel Griffiths, made almost as much again.

Foreign-language films included Lars von Trier's two-part hospital allegory The Kingdom (1994 and 1997) and, bringing Watson another Oscar nomination, Breaking the Waves (1996), as wellas Thomas Vinterberg's Festen (1998). The White Balloon (1995), directed by Jafar Panahi from a typically understated Abbas Kiarostami script, was one of the first Iranian new wave films to be seen in the US.

More mainstream fare came with John Dahl's neo-noir The Last Seduction (1994), while the cultish vampire film Nadja featured a cameo (and executive producer credit) for David Lynch. Three years later October backed Lynch's dark and almost impossibly labyrinthine thriller Lost Highway.

One of October's last films was Robert Altman's Cookie's Fortune (1999); that year the company was sold. Ray served on festival juries and the like but after a near-fatal car accident in 2000 he returned to the business. At United Artists he picked up Danis Tanovic's Balkan War drama No Man's Land (2001) which, though hardly a financial success, won Best Foreign Film Oscar. Michael Moore's gun-culture documentary Bowling for Columbine (2003) had been repeatedly shunned by other companies, but Ray's vision (though he hadn't seen it) was rewarded with the Best Documentary Oscar. A year later Hotel Rwanda picked up three nominations, but UA felt some of Ray's choices were too outré and he left that year.

He joined Sidney Kimmel Entertainment but, despite his enthusiasm, could not persuade them to take on a script he absolutely loved – The King's Speech. But Kimmell did want to move to the mainstream and Ray left for consultancies at the Film Society of Lincoln Centre, the Independent Film Channel and Snag Films. In 2011 he crossed the country to become Executive Director of the San Francisco Film Society.

Ray was a fixture at the Sundance Festival, whose founder, Robert Redford, described him as "a true warrior for independent voices ... a valued member of the Sundance family ... and responsible for mentoring countless seminal storytellers and bringing their work into the world." Here, at the epicentre of independent film-making, he struck deals for films that were so important to him that, he said, "I would chop off my left arm to do it." It was there that he succumbed to a stroke.

John Riley

Bingham Ray, film producer and distributor: born New York 1 October 1954; married Nancy King (three children); died Provo, Utah 23 January 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks