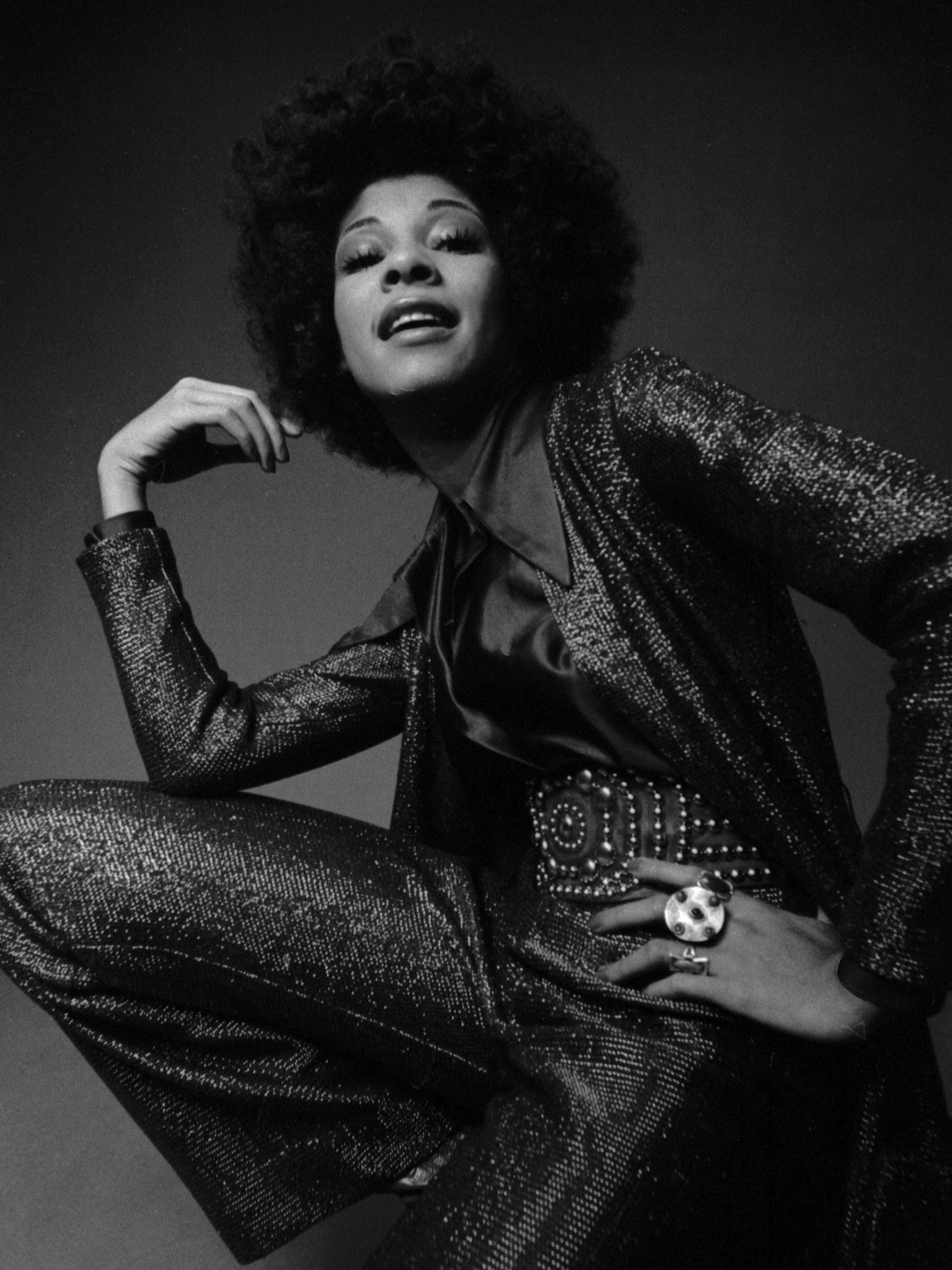

Betty Davis: Free-spirited queen of funk who inspired music greats

With her silver go-go boots, towering afro and uninhibited vocals, Davis was one of the most formidable performers of the mid-Seventies

Betty Davis, a free-spirited, genre-busting funk singer who influenced generations of artists with her libidinous stage presence, bluesy melodies and bold, uninhibited lyrics about sex, love and desire, has died aged 77.

With her silver go-go boots, towering afro and uninhibited vocals, Davis was one of the most formidable performers of the mid-1970s, strutting across the stage in lingerie or shiny, futuristic outfits. She considered herself “more of a projector” than a singer, and yowled, screamed and cackled, depending on the song, developing a raw and blistering brand of funk that drew on rock and soul, and that influenced artists from Prince to Janet Jackson.

“She seemed sure, free, bold and unafraid at a time when women and Black people were supposed to feel afraid or limited,” singer Macy Gray told The Washington Post in 2018. “And then Betty Davis comes along and rose above that on her own. She presented herself as someone who wasn’t [held] captive by all that. She seemed to fly and skip right over that and do her thing the way she wanted to do.”

Long before sexually explicit lyrics became commonplace, Davis recorded songs that were brazenly carnal, filled with lust and sly wit. “You said I loved you every way but your way,” she sang in the title track of her 1975 album Nasty Gal, “and my way was too dirty for you.” Her song “He Was a Big Freak” was more direct, opening with the line, “I used to beat him with a turquoise chain.”

“I wrote about love, really, and all the levels of love,” Davis said in a 2018 interview with The New York Times. Naturally, she added, sexuality was one of her chief subjects: “When I was writing about it, nobody was writing about it. But now everybody’s writing about it. It’s like a cliche.”

Davis also wrote songs about racial discrimination, music history, and the sheer exhaustion of being alive in the 1970s. (“The blues are taking over, and they’re running my soul.”) But her erotic lyrics infuriated religious groups as well as the NAACP, which boycotted Black radio stations that played her music, saying she was a bad role model for African Americans. After releasing three critically acclaimed albums in the span of a few years, she retreated from the music industry in the late Seventies, fading from public view.

By then, she had helped alter the trajectory of jazz through her relationship with trumpeter Miles Davis, whose name she kept long after their brief marriage ended in divorce. Davis introduced her husband to rock artists Jimi Hendrix and Sly Stone, helping to pave the way for electric albums such as Bitches Brew (1970), a landmark in the burgeoning genre of jazz fusion. (As she told it, Miles had planned to title the album Witches Brew before she suggested an edgier name.)

Davis later reached new listeners through hip-hop. After Light in the Attic Records reissued her albums in the 2000s, she was increasingly cited by musicians who celebrated the fiery independence of an artist who wrote, arranged and produced her own records.

“I love Betty Davis. She’s free, and she’s one of the godmothers of redefining how Black women in music can be viewed,” Janelle Monae told Complex magazine in 2018. Looking back at Davis’s legacy that same year in a conversation with the singer-songwriter Joi, Erykah Badu concluded, “We just grains of sand in her Bettyness.”

Betty Mabry was born in New York on 26 July 1944, and grew up in rural North Carolina and in Homestead, just outside Pittsburgh. Her father worked at a steel mill, and her mother and grandmother encouraged her love of music, especially the blues.

By age 12, she was writing songs of her own, including a number titled “I’m Going to Bake That Cake of Love”. She later paid homage to the blues artists who had shaped her childhood in “They Say I’m Different,” namechecking artists including Elmore James, John Lee Hooker, Robert Johnson and Jimmy Reed.

After graduating from high school, Davis moved to New York, where she studied at the Fashion Institute of Technology and worked as a model. She appeared in magazines such as Glamour and Seventeen – a rarity for a Black woman at the time – and also made connections in the music industry, meeting artists at a club called the Cellar.

She released her first commercial single, “Get Ready for Betty”, in 1964, but found far greater success as a songwriter when the Chambers Brothers recorded her song “Uptown” three years later. Around that same time, she met Miles Davis; as she told it, she was at one of his Village Gate performances when the trumpeter spotted her and dispatched his bodyguard to invite her over for a drink.

Davis and Miles married in 1968 – he was 42, she was 24 – and divorced after what she described as a tumultuous and sometimes violent year. He suspected her of having an affair with Hendrix, which she denied.

“I learned a lot musically,” she told the Post in 2018, looking back on their marriage. “I always said to Miles, ‘I should have been born your daughter.’ Because our relationship was very enlightening as far as my music was concerned.” Miles, who had her face photographed for the cover of his album Filles de Kilimanjaro, introduced her to classical music and encouraged her to sing, producing recording sessions that were eventually released in 2016.

Davis’s early studio work attracted the interest of Greg Errico, the drummer for Sly and the Family Stone. He produced and drummed on her self-titled 1973 debut, which included songs such as “Game Is My Middle Name”, while Davis took over production for her 1974 follow-up, “They Say I’m Different”.

In addition to Errico, her records featured leading musicians including bassist Larry Graham, the Pointer Sisters and members of the Tower of Power. But by all accounts, it was Davis who conceived and orchestrated the ensemble’s overall sound.

“Betty would get the ideas for the music, and she would put it on tape. She’d be humming on the cassette, and we’d learn all the parts,” backing guitarist Fred Mills told the Times. “She had it in her head all the time. And she would always be, like, ‘You got to get rough!’ Lord have mercy, she was killing me.”

Davis earned some of the best reviews of her career with Nasty Gal, which she recorded after signing a major contract with Island Records. But the album’s sales were disappointing, and the label decided to shelve her follow-up. No one else came calling, she said.

After her father died in 1980, she spent a year in Japan, meeting silent monks at Mount Fuji and experiencing a kind of spiritual awakening, according to the 2017 documentary Betty: They Say I’m Different. She returned to the US, and, she said, “I just got very quiet.” By 2018, she was living in Homestead at an apartment for senior women run by Catholic Charities USA.

She leaves no immediate survivors, according to her friend Danielle Maggio, a singer, ethnomusicologist and associate producer of Betty.

In 2019, Davis wrote and produced her first song in 40 years, “A Little Bit Hot Tonight”, with Maggio singing lead. By then she had ruled out a return to the stage, saying she treasured her anonymity and didn’t want to alter the image that fans had in their minds.

“I like that nobody knows who I am when they see me. I like to live quietly,” she told the Post. “But it would be nice to be remembered that at one time, she made good music and she made people smile.”

Betty Davis, singer, born 16 July 1944, died 9 February 2022

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments