Arthur Mitchell: Trailblazer of ballet who ran circles around racism in America

He braved racist taunts for doing what he loved best – dancing – but once his talent was embraced by the great George Balanchine he was unstoppable

Making his debut in 1955 as the first African American dancer with the New York City Ballet, Arthur Mitchell, who has died aged 84, faced racist catcalls from the stalls.

But when the people who thought there was no place for a black man in ballet called for Mitchell’s removal, no lesser luminary than the great choreographer George Balanchine announced: “If Mitchell doesn’t dance, New York City Ballet doesn’t dance.” He might just have well have said “New York City doesn’t dance”. Mitchell would go on to be at the heart of American ballet for the next half-century, founding his own company, the Dance Theatre of Harlem, to ensure that the African American dancers who followed him would get their chance.

Arthur Mitchell was born in Harlem, New York. He was one of six siblings. His father, a building superintendent, was sent to prison when Mitchell was just 12. The sudden change in the family’s circumstances forced Mitchell to become a breadwinner, taking on several jobs to make ends meet. He worked as a shoeshine boy and in a butcher’s shop.

Fortunately, Mitchell still found time to go to the local Police Athletic Glee Club, where he learned to tap dance. Encouraged by a school counsellor, he auditioned for the New York High School of Performing Arts. His performance of Astaire’s “Top Hat, White Tie and Tails” won him a full scholarship.

Though at the time, black students at the arts school were encouraged to pursue modern dance as a career, Mitchell’s teachers recognised his aptitude for ballet from the beginning.

Upon his graduation in 1952, Mitchell was offered not one but two scholarships. He took the scholarship offered by the School of American Ballet, the affiliate school of the New York City Ballet. Three years later he made his debut with the New York City Ballet Company in the fourth movement of Balanchine’s Fourth Western Symphony.

During the Fifties, racism was rife in the ballet world. While modern dance was more integrated, thanks to the likes of Martha Graham, ballet companies were still almost entirely white. Mitchell’s 1955 performance caused a furore not only in the audience but amongst outraged WASP parents who threatened to pull their precious daughters from the ballet’s chorus.

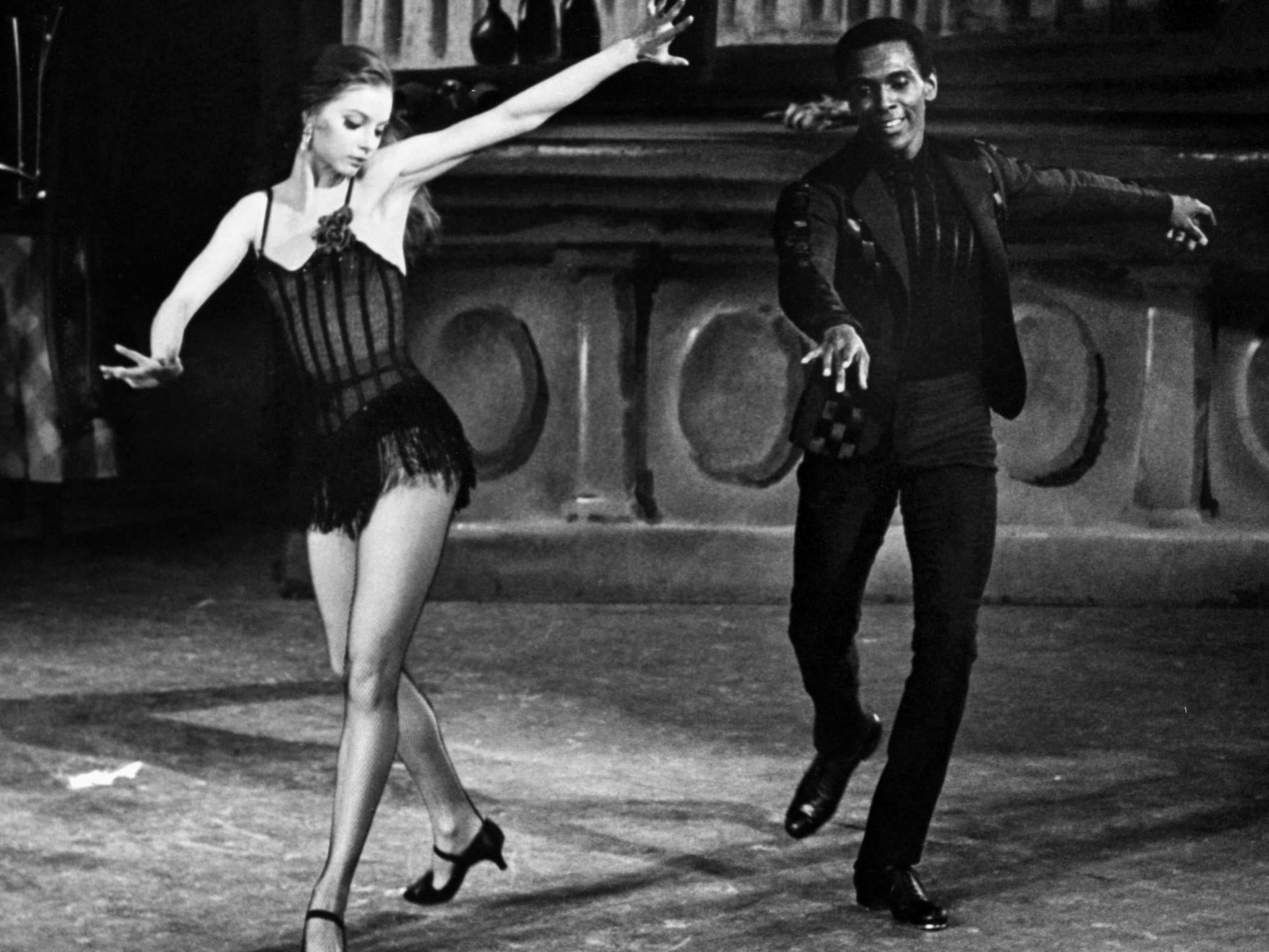

Balanchine, however, stuck by his decision to cast Mitchell in a leading role and in 1957 he faced down racist criticism again to create for Mitchell a pas de deux in his ballet Agon. Mitchell’s partner for the dance was white ballerina Diana Adams.

Talking about Balanchine to The New York Times, Mitchell said: “Can you imagine the audacity to take an African American and Diana Adams, the essence and purity of Caucasian dance, and to put them together on the stage? Everybody was against him. He knew what he was going against, and he said, ‘You know my dear, this has got to be perfect’.”

The dancing may have been exquisite, but in a country still riven by segregation, the pairing was scandalous. Mitchell would dance the Agon pas de deux with white ballerinas all over the world, but it was not until 1968 that he was able to partner a white dancer on American commercial television.

During his time at the New York City Ballet, Mitchell became the company’s principal dancer and his repertoire grew to encompass all the classics. Balanchine continued to use Mitchell whenever he could, most notably casting him as Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In 1966, however, Mitchell left the NYCB to work in Washington DC and in Brazil, where he founded the National Ballet Company of Brazil. His return to New York was catalysed by the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. The horror of the killing made Mitchell determined to help the black community in which he was raised.

When he was invited by soprano Dorothy Mayer to create a dance programme for her Harlem School of The Arts, Mitchell jumped at the opportunity. The programme began in a church basement with just 30 students but by the end of the first term, attendance had swollen to 400. In partnership with renowned ballet master Karel Shook, Mitchell began his own dance school, The Dance Theatre of Harlem. It was housed in a converted garage on 152nd Street, in the neighbourhood where Mitchell had grown up.

Mitchell based the its dance curriculum on the tuition he himself had received as a young dancer, but as head of his own company, he was finally able to mould the ballet world to his vision. The company danced the classics and the works of Balanchine but also introduced new ballets celebrating African American culture. In 1984, Mitchell took Giselle and set it in the Louisiana bayou. When the ballet premiered at the London Coliseum, it received the Olivier award for outstanding dance production of the year, though it wasn’t until three years later that it would be broadcast on US public television.

In 1992, the company was invited to South Africa but Mitchell was unconvinced that the dance theatre should perform in a country still struggling to emerge from the shadow of apartheid. It took a call from Nelson Mandela himself to persuade Mitchell to take up the invitation. Mitchell’s subsequent visit to the townships spurred him to take the Harlem company in a new direction. On his return to New York, he created an outreach programme, Dancing Through Barriers, to take the theatre’s ethos all over the world.

In 2006, nearly 40 years after it began life in that garage, the school of the Dance Theatre of Harlem gave a performance at the White House, followed by a dinner dance hosted by President Bush. While Al Green sang “Let’s Stay Together”, Mitchell persuaded Laura Bush to join him onstage for a very special pas de deux.

From a young dancer abused by racist audiences, Mitchell had become a ballet grandee with presidential approval. He was already a recipient of the Kennedy Centre Honour and a MacArthur Fellow. In 1995 President Bill Clinton presented Mitchell with the United States National Medal of Arts. But alas, such approval didn’t correlate with increased funding. The early 2000s were difficult years and the Dance Theatre of Harlem Company had to take a hiatus between 2004 and 2012.

Today, the Dance Theatre of Harlem reaches more than 1,000 people a year through its dance programmes. In alignment with its mission to provide arts education, community outreach programmes and positive role models for all, Dancing Through Barriers is open to anyone who wants to dance, from children to pensioners. The Harlem company continues “to present a ballet company of African American and other racially diverse artists who perform the most demanding repertory at the highest level of quality”.

Though Mitchell stepped down from the the Dance Theatre almost a decade ago, he was involved in the restaging of one of his ballets to be performed at the company’s 50th anniversary. Also this year, in an interview with the New York Times, Mitchell said of the audiences that once found his presence on the ballet stage scandalous: “I danced myself into their hearts.” But at the same time he observed that African American dancers are still underrepresented in the ballet world and added: “There’s still work to be done.”

He is survived by his niece, Juli Mills-Ross.

Arthur Mitchell, dancer, born 27 March 1934, died 19 September 2018

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks