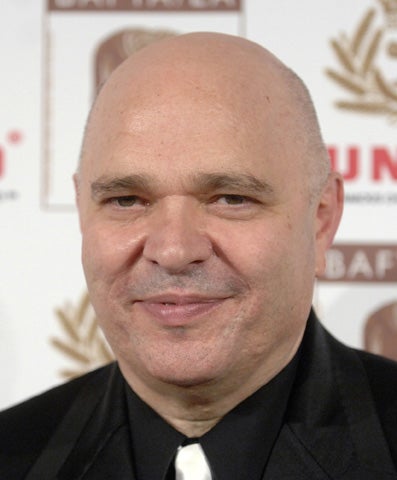

Anthony Minghella: Oscar-winning director of 'The English Patient' who was unafraid to deal frankly with raw emotions

Anthony Minghella made relatively few features and his career as a movie director lasted under two decades. None the less, he is likely to be remembered as a significant figure. Not only was he prepared to take on major literary novels like The English Patient and Cold Mountain, he was unafraid to deal frankly and without embarrassment or irony with raw emotions. Detractors may have called his approach novelettish and accused him of at least occasional mawkishness, but he was able to engage with audiences on a level that many, more timid, British directors of his era were not.

Minghella traced his passion for cinema back to his childhood on the Isle of Wight. His parents had a café which was open almost the entire year round. At a certain point, his nights became his own because his parents weren't there to supervise him. They came home one evening when Anthony was eight or nine and found him completely devastated, in front of the television. He had been watching Josef Von Sternberg's The Blue Angel, starring Marlene Dietrich as the femme fatale who seduces and humiliates an upright, middle-class schoolteacher.

"What I remember was that it was the first time a piece of fiction had had such a devastating emotional effect on me," he recalled. "It was the first time I realised there was an adult world – that adults could damage each other or destroy each other emotionally."

He spoke of how the film showed him that "love can be a rupturing and damaging emotion as well as a healing one" and of his shock at seeing someone like the teacher, in "an authority position made so small, so diminished, by the feeling of having no control".

These remarks about love being a rupturing as well as a healing emotion take on an added resonance when one thinks of his most celebrated feature, The English Patient (1996), for which he won an Academy Award, one of nine Oscars the film received. Here, as in several of his other films, Minghella showed a knack for taking the ingredients of the typical love story and treating them with intelligence and lyricism.

What also impressed was the sheer size of the film. At a time when many British directors were making introspective chamber pieces, Minghella was tackling large subjects. The film had a famously troubled production history, eventually being "rescued" by Miramax. This only seemed to add to its mythic status. Minghella proved that he was a craftsman, capable of staging big set-pieces and working with small armies of extras, but he was also adept at capturing emotion in scenes between just two actors. He made an international star out of Ralph Fiennes and also elicited one of the very best performances that Kristin Scott Thomas has ever given.

Minghella was equally assured working on an epic canvas (as with The English Patient and his later film Cold Mountain) and in dealing with similar themes on a much more intimate scale, as in his début feature, Truly, Madly, Deeply (1990), with Juliet Stevenson haunted by her former lover Alan Rickman. The film explored some of the same themes as the Hollywood tearjerker Ghost, but Stevenson and Rickman brought an irony and a subtle emotionalism to their performances that was well beyond the capacity of Patrick Swayze and Demi Moore.

Similarly striking was Minghella's adaptation of Samuel Beckett's Play (2000). This was essentially just three talking heads but the film had the impact and intelligence of his more conventional films. There were magnificent moments in Cold Mountain (2003), notably an early battle sequence that even an old master like D.W. Griffith would have been proud of, and some fine acting, particularly from Nicole Kidman. The Talented Mr Ripley (1999) meanwhile was a superbly constructed thriller with real psychological depth in which Minghella managed to make us care about the psychopathic but oddly naive Tom Ripley, despite his misdeeds.

Anthony Minghella was born in Ryde in 1954, the son of Edward and Gloria Minghella, both of Italian immigrant stock. His parents' cafeteria was next-door to a cinema. As a child, he had "free and unfettered access to the projection room", from where he could watch movies, enjoying his own "mini Cinema Paradiso experience". He hoarded film posters for his bedroom and also sold ice-cream in the cinema during the intermission.

Much of his time as a child was taken up with working for his parents, and access to high culture was limited. Not that he begrudged his circumstances:

I have never resented my childhood. It was a blessed childhood in the sense that I had a wonderful family. I don't resent the lack of cultural information I had as a child. It made me very inquiring and curious. I've always imagined that you find your culture rather than receiving it on a plate.

The young Minghella was a voracious reader, although "My parents didn't have any books at all. We had not a shelf of books. So we found books from the library, but also books lying around to pick up." Religion was also an important factor in his childhood. His parents were strict, church-going Catholics and Minghella was taught by nuns until he was 18. However, he was growing up in the turbulent 1960s, when hoary old ideas about class, education and culture were beginning to be questioned, even on a small island like the Isle of Wight which – as he quipped – was "two hours and 20 years from London".

Movies which had a key formative influence on him were Lindsay Anderson's If . . . and Federico Fellini's 1953 classic I Vitelloni. It is easy to see why Fellini's film so appealed to him. Set in a small Italian seaside town just after the Second World War, it was about a group of wild young friends in the provinces – only one of whom ultimately manages to escape to the big city.

Like the narrator of I Vitelloni, Minghella made his own journey away from his Isle of Wight roots. He and his friends had long tried to imagine what life across the water would be like:

It's four miles away. For 90 per cent of the year, you can stand on the shore and you could be looking on the other side of the street. And yet it has another set of values. It is the unknown. We all imagined a world that we would get on the ferry and go off to and find ourselves.

Minghella's early aspiration was to be a songwriter. He knew musicians but confessed he had "never seen anyone with a camera". His film-making career began almost by accident. When he was in his third year at Hull University, he started to write a musical. He wanted to include an exterior sequence. The drama department had a Bolex camera which he was allowed to borrow. Having shot a short piece of footage, he resolved to make a full-length film and borrowed money to finance it. It took him nine years to pay back the loan and the film turned out disastrously. None the less, he saw this – at least with hindsight – as a useful introduction to the vagaries of film production. He learned "how much it takes of your resourcefulness and will-power to make a film but also how addictive and extraordinary it is".

Minghella graduated from Hull in 1975 with a First in Drama. He returned to Hull to lecture for seven years while studying for a doctorate. When he finally started directing professionally, he said he felt like a man who had discovered his hobby could be his job. By then, he had served a stint as a television script editor on Grange Hill during the 1980s. He worked as a script editor and writer for series including EastEnders. He wrote episodes of Inspector Morse and won plaudits for his 1986 play, Made In Bangkok. His début feature Truly, Madly, Deeply was made for BBC TV but released as a film. A foray to Hollywood to make the romantic comedy Mr Wonderful (1993) was not especially successful.

His real breakthrough as an international-class film-maker came with The English Patient. Minghella's triumph was to take Michael Ondaatje's award-winning but very complex and literary novel and to turn it into a big-screen epic romance with the sweep of an old David Lean movie.

Not all his subsequent movies achieved the same level of success. The Talented Mr Ripley stands alongside Alfred Hitchcock's Strangers On a Train as one of the best Patricia Highsmith adaptations but Cold Mountain was given a mixed reception and failed to repeat the success of The English Patient. Breaking and Entering (2006) was on a smaller scale. Despite respectful reviews, it made little impact at the box-office.

Alongside his own career as film director, Minghella was also active as a producer and as an opera director. He recently stood down as chairman of the British Film Institute. His final film, The No 1 Ladies' Detective Agency, shot in Botswana, is due to be broadcast by the BBC on Sunday.

Geoffrey Macnab

Prior to his international movie career, Anthony Minghella had gradually built up a reputation as one of the most distinctive and consistently adventurous British playwrights of the 1980s, writes Alan Strachan. Stamped always by an unforced and unsentimental humanism, his work tackled an unusually wide range of subject matter, as it moved confidently from small-scale studio-theatre pieces to the more demanding exposure of the commercial sector.

An early play, Whale Music (Hull, 1980) demonstrated his special gift for creating rich roles for women; with an all-female cast it explores the lives of a diverse group in a seaside town waiting for a student friend to give birth. Written in short scenes – which worked better technically in a subsequent television version – it was by turns tender and very funny, with a memorable diatribe from the drifter Stella, corrosively describing the men encountered in her one-night stands.

A Little Like Drowning (Hampstead, 1984) similarly was constructed in brief vignettes, but ambitiously spanned and often intermingled the years, with its fulcrum in the slow collapse of an Anglo-Italian couple's marriage. Time and space mingled with assured aplomb, as they did in Love Bites (Derby, 1984) which likewise mined aspects of Minghella's own Anglo-Italian inheritance. Set initially in wartime England and centred round two brothers establishing their ice-cream business, the second act leaps the years to the present day in a convention hotel. Minghella handled a large cast and canvas with unobtrusive skill, painting a vivid picture of tribal relationships and schisms.

Moving completely away from such material Minghella came up with the surprising and beguiling Two Planks and a Passion (Exeter, 1983 and Greenwich, 1984) set in late 14th-century York where a careworn Richard II, accompanied by his queen and his friend the Earl of Oxford, have escaped courtly pressure while the workmen's guilds prepare the York Mystery Plays for performance during the Feast of Corpus Christi. Alongside some splendid comedy – the King teasing the unctuously fawning Mayor during an innovative golf game – the play, warmly glowing, became ultimately most affecting in Danny Boyle's production as it moved into a powerful performance of the Mysteries witnessed by the royal party.

The commercial producer Michael Codron, ever-alert to new theatrical talent, had had his eye on Minghella's work and commissioned the play which marked the dramatist's West End début, Made in Bangkok (Aldwych, 1986). This was a dense, dark study of personal and cultural exploitation; again Minghella displayed his gift for ironic comedy and that special touch with female roles, creating a strong, complex central character in Frances (Felicity Kendal), wife of a devious and ultimately frightening businessman.

Some scenes – not least that in which a repressed homosexual dentist finally makes a sickeningly sad bid for the favours of the hotel-worker who has helped him as a guide in Bangkok – were strong meat for the world of Shaftesbury Avenue and Made in Bangkok had undeservedly only a moderate West End run.

With the success of Truly, Madly, Deeply, Minghella began the screen career which soon became so crowded that sadly no more work for the stage was forthcoming. A kind and gentle man, he was an ideal theatrical collaborator, tactful with actors and directors alike. That he had the instincts of a fine stage director himself was abundantly evident in his bravura handling of all the elements of opera in Madam Butterfly (Coliseum, 2006) for ENO.

I once asked Anthony Minghella why he never moved to Hollywood after his success with The English Patient, writes Roger Clarke. "I'd go nuts," he replied. Months later we were having dinner at the Michelin-starred Hakkasan restaurant with his lovely wife Carolyn and his son Max – and he wasn't enjoying himself. He would far rather be eating in Yming down the road, he admitted, a very old-fashioned Chinese restaurant in Greek Street where you can actually have a conversation. The demented roar of a voguish restaurant just wasn't for him. "We don't actually go out all that much," he said, as he looked around at the multi-million-pound décor with a kind of puzzlement.

Anthony always stayed close to his roots on the Isle of Wight. He ascribed his love of the noise and bustle of the film-set to those days. Later his collegiate style, paradoxically quite mandarin, was brought to the chairmanship of the BFI. He was a steadying influence there, at a time when steadying was desperately needed. His gentle manner was that of an encourager and an enthusiast. He would bring you into his fold. You were treated like a family member whenever you saw him. Nothing was forced, or false, not for one minute. You can say that about few people in the movie business.

I saw him, last year, by chance, at a ceremony in the French ambassador's house when Jude Law was receiving an award from the French government; Anthony and Carolyn were a few of a handful of guests invited by Law to be present at a meal afterwards. I had no idea they were so close, but Anthony Minghella was beloved by nearly all the actors he worked with. We all thought that in 40 years' time, Lord Minghella of Wight would be the Richard Attenborough of our times, handing out benedictions on stage to a long and rousing applause.

Anthony Minghella, writer and film director: born Ryde, Isle of Wight 6 January 1954; Lecturer in Drama, Hull University 1976-81; CBE 2001; chairman, BFI 2003-08; twice married (one son, one daughter); died London 18 March 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks