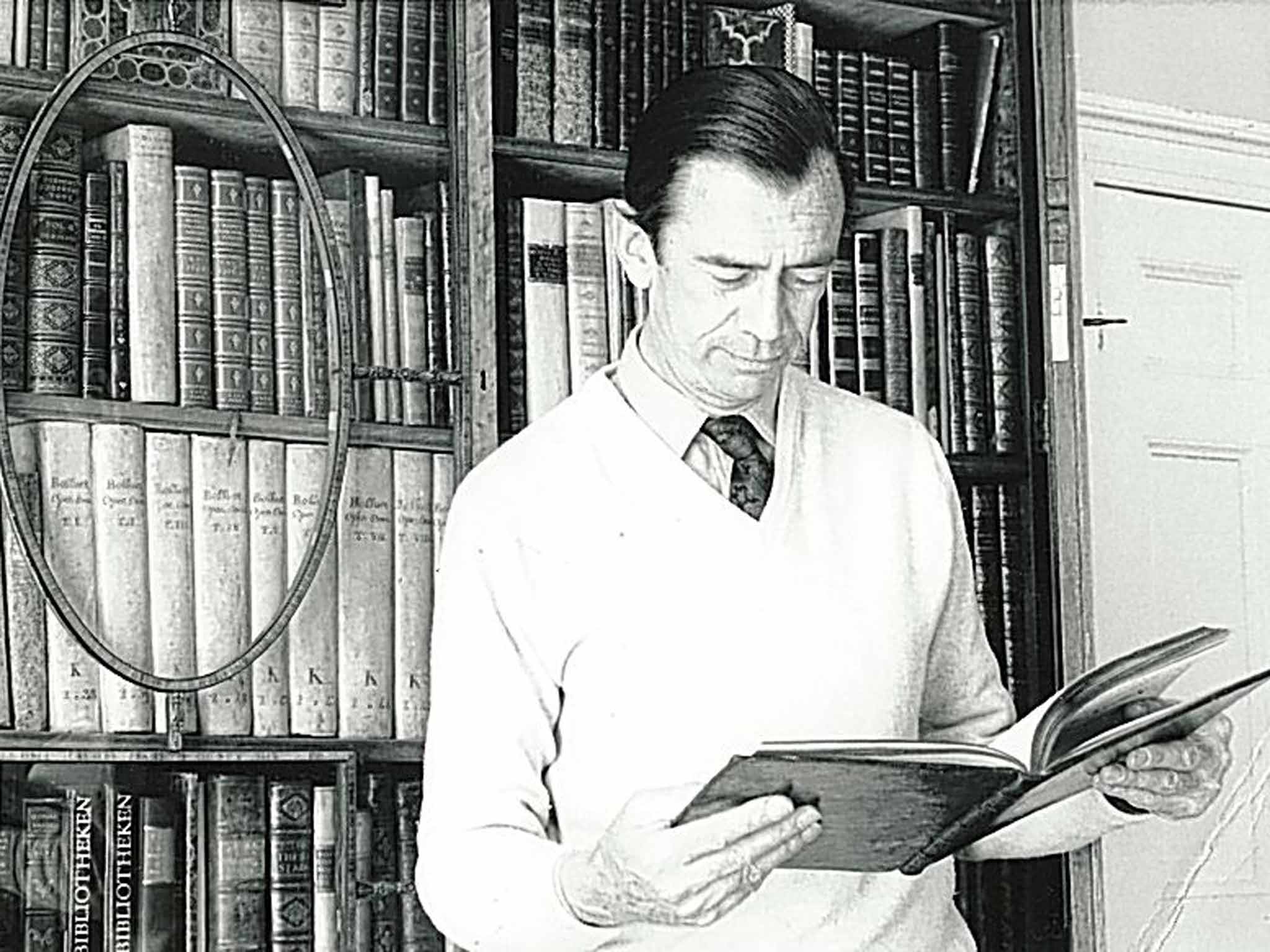

Anthony Hobson: Historian, auctioneer and scholar who followed his father as a leading figure in the study of bookbinding

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Bookbinding is an arcane craft that became an art – and the subject of two great historians, Geoffrey Hobson (1882-1949) and his son Anthony, who has just died aged 92. Both found time for it when spared from the business of Sotheby's, the auctioneers.

Geoffrey Hobson was one of the group which bought the firm in 1908. He could not take sales due to deafness, but was a master of every other aspect of the business, most of all the cataloguing of books. Early English and later European gilt bindings became his province, on which he wrote five great books. In 1920 he married Gertrude Adelaide, daughter of Thomas Vaughan, rector of Rhuddlan, a war-widow.

Their only son was born next year at Rhyl, near her parents' home. He grew up in his father's fine London house, 1 Bedford Square – left, sadly, in 1932 when the British Museum commandeered the garden to build the Duveen Gallery. By then he had gone to Sandroyd School, then to Eton as an Oppidan Scholar.

There he gained admission to the College Library, rarely granted to boys. Interested in medieval manuscripts, he asked to see the Eton Apocalypse; the Provost, he recalled, "held it open as far away from me as he could." Then and later, nothing stopped him seeing books, no matter how remote or difficult of access. He learned more on many visits to France and Switzerland with his parents. He became an expert skier while his invalid mother took the waters at Carlsbad. She died in November 1938, leaving son and husband bereft.

In January 1940 Hobson went up to Oxford to read Modern Languages, especially French literature. He took a war-shortened BA and joined the Scots Guards. In 1943 he was posted to the 2nd Battalion, and served throughout the Italian campaign with 201 and 24 Guards Brigades. He was mentioned in despatches on 7 June 1944 for retrieving under fire at Civita Castellana a German map with the exact course of the Gothic Line traced on it.

He ended the war as GSO III (Intelligence), 6 Armoured Division, released in October 1946. Sotheby's beckoned, but he was worn out and needed a year off. He went back to Italy, to Greece, Turkey, Spain and Portugal, seeing (and remembering) the art and architecture of the Mediterranean; he added Italian and Spanish to respectable French and German.

He joined Sotheby's in September 1947. Although the firm was unscathed the burden of maintaining it during the war had fallen on his father. He remained to superintend the Landau-Finaly sale in 1948, but on 4 January 1949 he died, to be succeeded by Charles des Graz. If his father had been Anthony's mentor in scholarship and the interior business of running Sotheby's, Des Graz taught him its outward face. He took the sales that his father could not with practised skill. Immaculately dressed, a disciplinarian to his fingertips, he taught Anthony how to take a routine sale fast without missing a bid. Hobson took sole charge when Des Graz died in 1953.

The change was seamless. However urbane, he inherited his father's insistence on discipline, in the book department and sale-room. This was put to the test in the Dyson-Perrins sales of medieval manuscripts in 1958-60. Hobson set new scholarly standards in the catalogues, which he wrote himself. The sales, which he led from the rostrum, beat all records.

This prepared the way for the ultimate challenge, when the residue of the great Phillipps collection was consigned by the Robinson brothers in 1965. Hobson masterminded a sequence of sales that lasted for 12 years, during which he also saw to those of CE Kenney's scientific books, the fine bindings and manuscripts of Major Abbey, his father's old friend and his own, and many others.

Disenchanted by Sotheby's new predatory direction of, bent on global dominance, he gave up his directorship in 1971, but not responsibility for the Phillipps sales, and remained a consultant. He was also Sandars Reader in Bibliography at Cambridge in 1974-75 and Lyell Reader at Oxford in 1990-91, President of the Bibliographical Society, 1977-79, and a Fellow of the British Academy in 1992; he was a trustee of the Eton College Collections Trust and Lambeth Palace Library.

As president of the Association Internationale de Bibliophilie (1985-99) he transformed the task of organising its annual séances all over Europe, exploring every site in advance, attending every session and concluding each with an eloquent speech in the language of every country visited. Like his father he wrote books, beginning with French and Italian Collectors and their Bindings (1953), an astonishingly mature work for one just 30. Great Libraries (1970) followed, no coffee-table book but a serious account of the many he had visited.

There was then a change of direction. Apollo and Pegasus (1975) answered a question his father had explored, who was the owner of books bound with this device (a Genoese nobleman called Grimaldi, he found): it also showed how book-binding was part of a humanistic view of books. This theme continued in Humanists and Bookbinders (1989), his masterpiece, and in Renaissance Book Collecting (1999). He saw the late Albinia de la Mare's Bartolomeo Sanvito: the life and work of a Renaissance scribe to completion (2009).

He wrote almost 200 articles: a review of the great catalogue of the Waddesdon library was published only a few days ago. He also collected books, first 17th and 18th century Italian illustrated books, since dispersed, then the manuscripts and books of the writers of his time – many, notably Cyril Connolly and Anthony Powell, his friends. He published an elegant edition of Ronald Firbank's letters in 2001.

He never lost his upright military figure, even in old age. His marriage to Tanya Vinogradoff in 1959 and the children that they had brought a new warmth to his life that lasted after her untimely death in 1988. Her photographs enhanced his books, and they shared a love of opera, art and architecture.

He was a lively and curious traveller, a generous friend, particularly to younger scholars, but a resolute enemy to those he believed to be wrong. As a historian of books he saw, beyond the bindings that he knew so well, their full part in the culture that produced them; by that he will be remembered.

Anthony Robert Alwyn Hobson, auctioneer and historian of books: born Rhyl 5 September 1921; married 1959 Elena Pauline Tanya Vinogradoff (two daughters, one son); died Whitsbury, Hampshire 12 July 2014 .

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments