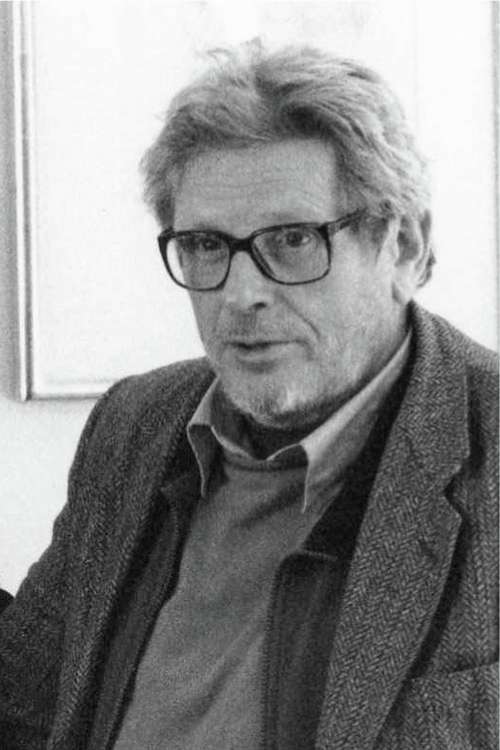

Angus Calder: Historian, critic and poet whose 'The People's War' challenged conventional wisdom on wartime Britain

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Angus Calder was for many years a conspicuous figure in the Edinburgh literary scene, but those who knew his prodigious output and his teaching career realised that there was much more to him than that genial presence in poetry readings, theatre, pubs and literary events all over Scotland.

His birth in 1942 into a writing family (his father Ritchie Calder was a well-known writer on scientific subjects), and his first marriage, to Jenni Daiches (daughter of the prodigiously gifted scholar David Daiches), ensured a life spent among books, authors, strenuous discussion and high standards. Ritchie Calder (later Lord Ritchie-Calder) had worked in London – giving young Angus a knowledge of the city and its social structures – before taking the Chair of International Relations at Edinburgh University; David Daiches was to end his long career as director of the same university's Institute of Advanced Studies. Angus studied English at King's College, Cambridge, and wrote his doctorate at Sussex University, its subject (Second World War politics in the UK) a good indication of where his interests lay, and would lie.

The two thrusts of Angus Calder's research and publishing interests were therefore established: well-researched and soundly based histories, and close studies of literary figures from 20th-century Scotland. Among his histories, the magisterial The People's War: Britain 1939-1945 (1969) was the first substantial work to question conventional wisdom on wartime Britain, and won him the Mail on Sunday/John Llewellyn Rhys Prize the year following publication. The revisionist theme continued with Revolutionary Empire (1981) and The Myth of the Blitz (1991).

His literary studies included Revolving Culture: notes from the Scottish Republic (1994), and an edited collection of Hugh MacDiarmid's prose, The Raucle Tongue: selected essays, journalism and interviews (in three volumes, 1997-98) – the latter, like many of his works, collaboratively edited.

These are merely high points: the very extensive bibliography of teaching books, introductions and collections, overlooking his own creative writing and five volumes of poetry, points to the other main thrust of his life, his long involvement with the Open University in Scotland where he inspired and nurtured the careers of a generation.

One other title, Russia Discovered: nineteenth-century fiction from Pushkin to Chekhov (1976) is (as I can testify from using it in university teaching for many years) exemplary of Calder's strong qualities: lucidity of organisation, the ability to connect across barriers of language and background to illuminate text, and a strength in overall construction which is particularly visible in his substantial historical writing. The Myth of the Blitz in particular is able to give a vivid picture of a complex society under stress to a generation born too late to have experienced it.

A particular strength of Calder's writing was his involvement with oral history, recording the experiences of those who had lived through such events as the Blitz and seen it at more uncomfortably close quarters than historians had done. Like all his historical writing, his depiction of London life at this extreme moment was characterised by lucidity: he did not obtrude on events so much as make them vividly alive to the reader.

Working in the Open University (from 1979 until 1993) gave Calder an unusual width of acquaintance in journalism, theatre and public affairs, an acquaintance which stretched far beyond Edinburgh and enriched committees and other bodies on which he sat. To the judging committee of the Saltire Book Awards, for instance, he brought a breadth of reference which illuminated all the discussions, and he often put forward forthright views on authors who might have been overlooked, or pushed to one side, without such a champion. He had the gift of fighting his corner with real energy, but remaining in the argument and joining in the decision with good grace.

The same qualities of openness and wide vision were to prove invaluable when the Scottish Poetry Library was in its infancy, its birth threatened by lack of finance and of adequate premises. As its first convenor, from 1982, Calder chaired the meetings, pursued the financial applications and saw through the project which has since grown to a purpose-built and splendid library off the Royal Mile in Edinburgh and, perhaps even more to his satisfaction, a notable travelling library which takes poetry out all over Scotland, while at the same time buzzing with creative writing, with energy and with argument.

This was the atmosphere Angus Calder breathed throughout his involvement with adult education and with literature, both inside and outside Scotland: in later years, as ill-health lessened his public visibility, he continued to animate it with his collections of verse: Waking in Waikato (1997), the wryly titled but very typical Horace in Tollcross: Eftir some odes of Q.H. Flaccus (2000), Colours of Grief (2002), Dipa's Bowl (2004) and Sun Behind the Castle: Edinburgh poems (2004). How typical that the titles span both hemispheres, several languages, and the assumption that Flaccus would be a recognisable name to all.

His was a wide view: he produced a lot of material to help others understand poetry, typically the 1996 cassette Women and Poetry (Approaching Literature), written and presented with Lizbeth Goodman. He was all-inclusive, as Andrew Marr picked up when writing the introduction to Sun Behind the Castle: "Calder's Edinburgh is also today's, with its rattle-bag of races and voices, its pizzas and Tesco superstores." Calder was in the best sense a thoughtful poet. There is a solitary feeling to his later writing, that of a man with a well-stocked mind and a huge experience, as well as linguistic flair.

His list of titles is a monument to be read with pride: Scotlands of the Mind (2002), Britain at War (1973), even briefer pieces, such as his introduction to the Penguin Great Expectations (1965) which generations of students have used with gratitude. Original, strong-minded, decisive, devoted to widening the discussion on every topic in every setting, Calder was someone who exemplified the idea of his title "Scotlands of the Mind". He lived most of his adult life in Scotland, and worked hard for it, but his mind never stopped pushing the boundaries.

Ian Campbell

Angus Lindsay Ritchie Calder, historian, writer and poet: born Sutton, Surrey 5 February 1942; editor, Granta 1962-63; Lecturer in Literature, University of Nairobi 1968-71; Visiting Lecturer, University of Malawi 1978; Staff Tutor in Arts and Reader in Cultural Studies, Open University in Scotland 1979-93; Founding Convenor, Scottish Poetry Library 1982-88; Visiting Professor of English, University of Zimbabwe 1992; married 1963 Jenni Daiches (one son, two daughters; marriage dissolved), 1986 Kate Kyle (née Young; one son); died Edinburgh 5 June 2008.

My first meeting with Angus Calder was, typically, at the bar of an Open University summer school where he was teaching, writes John Pilgrim. A group was noisily arguing about the Second World War. I told one of them loftily that he was obviously too young for the appropriate experience and that he should read The People's War. "Yes," said Angus, deadpan, "I think I might have a copy at home." It was three days before I realised to whom I'd been talking.

A shared interest in Duke Ellington (Angus had a perceptive and discriminating knowledge of all types of music) kept us in touch and later, when I was editing the journal The Raven, he was to save me from several shortfalls with some original essays. In particular there was an unfashionable defence of Samuel Smiles emphasising that Smiles was as much about mutual aid as individualism. Later, as an editor, he put a piece of mine into a hard-cover collection of essays. All who met him through the OU have reason to be grateful to him.

Even when times were difficult for him, he went to considerable trouble to assist struggling writers, offering hospitality in his house as well setting up introductions to suitable (and sometimes unsuitable) publishers. And those who heard it still dissolve into laughter at the memory of his deadly account of Cambridge student life with those who were to become Margaret Thatcher's cabinet. His table talk, by its ephemeral nature, is not much mentioned. But it showed the same erudition, perception, wit and above all originality, as his work in history, literature and music.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments