Andy Gill: Former chief music critic of The Independent whose wit earned fans and rocked bands

For years a stalwart of the print edition, taking genres from rock to classical in his stride, his breadth of knowledge informed reviews that struck fear and elicited joy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Andy Gill, The Independent’s former chief music critic, was a talented writer whose intelligent, witty critiques and features won him the respect of journalists, rock stars and music fans alike. His review of The Jesus and Mary Chain’s debut album took pride of place on the wall of the band’s record label Creation.

When Gill, who has died aged 66, interviewed Tom Waits in California for the cover of Uncut, the monthly he wrote for for many years, it was to the blues singer-songwriter’s publicist’s surprise that a 45-minute slot became a two-hour conversation. The interview began with a discussion of palindromes and flowed from there.

“Tom isn’t a fan of interviews, but really enjoyed talking to Andy,” PR Jakub Blackman recalls. “I’ve never seen Tom come out of an interview with a smile on his face. They really hit it off.”

Cornershop’s Ben Ayres recalls the band’s interview with Gill at the Vortex Jazz Club in 2002 – a time when they were burnt out from press attention. Ayres called it “the most interesting and thought-provoking” they ever did. “It was akin to talking to a fellow music head, his reading of the record we’d just made and his knowledge and understanding so refreshing, and it’s something we’ve always remembered. Andy was one of the great music writers of his generation.”

Kate Bush was so pleased with Gill’s review of her work that she told him she’d cut it out and used it to line her sock drawer, where she would see it every day.

Gill began his career as a freelance writer for NME in 1977, after answering the magazine’s legendary Hip Young Gunslingers advert, and was later appointed album reviews editor. His second piece for NME was a review of the prog-rock band Barclay James Harvest whom he, in his own words, “ripped to shreds”.

A couple of weeks later, he read in Sounds magazine that Barclay James Harvest had split up because of “a particularly harsh review in another music paper”. This story he enjoyed recounting to a friend in the lead-up to his death. “To this day he was delighted,” says music critic Gavin Martin. “How many writers can say they broke up a band with their second review?”

He joined The Independent as chief rock critic in 1990, and his tenure until 2018 made him the longest-serving weekly music reviewer on a national publication. As well as writing for The Independent, NME and Uncut, he was also a significant contributor to Q, MOJO, The Word and Empire. Even when illness had taken hold, he would make the journey to record-label offices to attend playbacks of new albums for review.

David Lister, Gill’s arts editor from 2002 until the closure of The Independent’s print edition in 2016, remembers the “big, burly, bearded presence” of “the doyen of rock critics” on occasional visits to the office.

Gill worked from home in Ilford, where he lived with his wife Linda, his childhood sweetheart. They had met aged 15 through Linda’s brother who ran a record shop in Sheffield, and were inseparable. Friends recall them as generous hosts holding Sunday garden parties with plenty of food. Gill was a foodie and celebrated his 66th birthday in February with family at his favourite restaurant, Provender, in Wanstead. It was their last meal out together.

The warm humour of his kind and gentle personality will be forever encapsulated by his 2009 interview with his namesake, the guitarist of rock band Gang of Four, for whom he was often mistaken.

Andy Gill the musician’s wife, the journalist wrote, insisted on taking a photograph of the two Gills together.

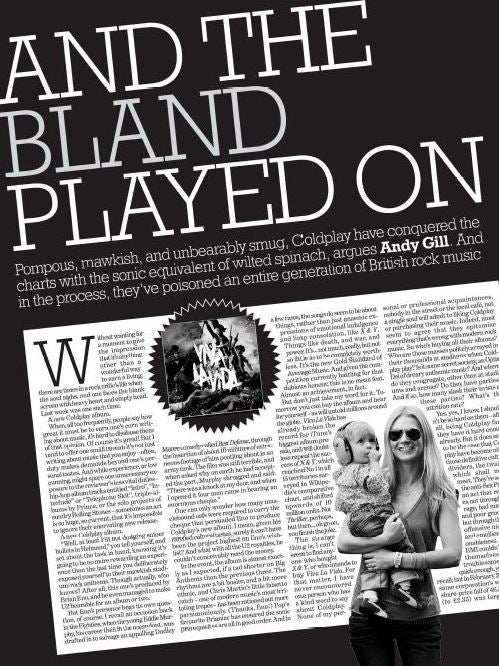

“I’m fed up having to deny I’m married to you,” Catherine Mayer said – no wonder: as her husband put it on Twitter this week, when The Independent’s man wrote a piece called “Why I hate Coldplay” in 2008, he “got an earful from their manager”. (In print the headline was the less sensational: “And the band played on”.)

“There was sometimes genuine fear in the industry about a bad review from Gill,” says David Lister.

Gill wrote of the band: “Their music sounds like Radiohead with all the spiky, difficult, interesting bits boiled out of it, resulting in something with the sonic consistency of wilted spinach.”

Once, Gill was thrilled to receive a signed letter from Phil Collins. It said: “After reading your review of my song ‘Another Day In Paradise’ I have come to the conclusion that you are the most cynical bastard in Britain.”

Gill had the letter framed and positioned it on his desk. There was also a letter of praise and gratitude from the late Michael Powell after Gill interviewed him and wrote a perceptive feature on the legacy of The Archers production company.

Aside from the big releases of the week, Gill had free rein over which albums to review for The Independent and his open-mindedness ensured that he gave his attentive analysis to all genres of music. On Twitter, the singer-songwriter Thea Gilmore posted: “So sad to hear that Andy Gill (journalist) has died. He reviewed me many times and his love and respect for music (even if he didn’t like it!) was so apparent in his work.”

His genuine enthusiasm meant he enjoyed new artists as much as veterans, such as his favourite artist of all time, Bob Dylan – the subject of his two published books. Close friend Pete Dolan remembers his “deep love for such a wide breadth of music from modern classical to folk to jazz”, in particular Miles Davis and Frank Zappa, and his honesty when it came to expressing his views. “He was just really honest about how he felt and that’s what was so endearing.”

Gill impressively widened his repertoire to include classical music when asked, late in his career.

“I looked forward each week to Andy’s elegantly written, stylish, incisive and sometimes, deliciously, very cutting reviews,” says Lister. “I was always amazed by the breadth of his expertise and enthusiasm. He may have come from the generation that adored indie-rock bands and famed singer-songwriters, but he embraced, and was deeply informative about, every musical genre.”

Lister adds: “When I asked if he would consider adding classical music to his brief, he did so without batting an eyelid, and so every week in The Independent was a double spread of Andy Gill reviews, encompassing all music from rock to pop to Simon Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic. Eschewing the sort of language that too often makes classical music reviews inaccessible, he made it come alive for the general reader. I’m not sure any other rock critic could have taken on, with such expertise, so wide a brief.”

Andrew Raymond Gill was born and raised in Sheffield with his older brother Steve, by his mother, a secretary, and father, a bricklayer. The family moved to Nottingham when his father took on a new job there as a civil servant.

Gill would later read sociology at the University of Sheffield and edit its student journal. In the Seventies, the Sheffield Wednesday fan left his hometown for London.

He attended Bramcote Hills Grammar School in Bramcote, Nottingham, where he was always in a band and would often be seen with a new record tucked under his arm. He long continued to dabble in his own musical projects, mainly in electronica.

As teenagers, he and his brother would battle over the record player their father bought them to share. “It was lugged from room to room,” says Steve. “Our taste in music was very different at that time. Andy was into folk – Bob Dylan, Simon and Garfunkel – and I was a soul boy, so when we were playing our music we did so with the delight that we were antagonising each other. In later years we both begrudgingly admitted to each other that we did actually quite like each other’s taste, but were never going to admit it because of that sibling rivalry.” The brothers would save up to buy records.

Gill was academically gifted, with something of a photographic memory, and had a rebellious streak which ran throughout his life.

“Times were fairly hard, so Andy did a paper round,” says Steve. “He used to spend so much time reading the newspapers and the pornographic magazines that he was supposed to be delivering that he always missed the school bus. He would then hitch a ride to school from anybody and arrive late. The school assembly looked out on the main entrance, which was for sixth form and staff only, and we would all see Andy walking up, waving across at us as we sang hymns.”

An excellent rugby player, Gill was selected for the school team, but games clashed with his Saturday job, and his suggestion that the school pay him what he would have earned resulted in temporary suspension. “They were outraged he could turn down the honour of representing the school,” says Steve. “The signs of rebellion were always there. He hated the establishment.”

Music journalist and author Mat Snow, who met Gill when he was album reviews editor at the NME, says: “I was one of the many writers to whom he not only gave a chance, but a great deal of help. Andy was a curious thing: he could be very sharp in his critical assessments of music which he didn’t care for, which he felt was bogus, but in person you would not meet a more warm-hearted, generous, kind person. I don’t think anybody who knew Andy has a mean thing to report about him. He was just a soul of benign-ness. He wasn’t tall, about 5ft 7in, and pretty rotund, with a beard, but he had an air of geniality about him which was genuine bonhomie. He was a bon viveur of the hippie generation.”

Gill, who died of cancer, is survived by his wife Linda, brother Steve, niece Claire and nephew Alex.

Andy Gill, music critic, born 28 February 1953, died 9 June 2019

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments