Alexander Cassie: Bomber pilot who helped forge false papers for 'The Great Escape'

Flight Lieutenant Alex Cassie was one of the forgers whose painstaking work made possible the Second World War prison camp break-out that became known as "The Great Escape."

The impromptu lecture on psychology that Cassie delivered to fellow prisoners to avert discovery by a snooping German guard was the model for the scene in the 1963 film in which Blythe the forger gives a talk on birdwatching.

The character played by Donald Pleasence was a sadder one than Cassie, who neither took part in the escape down the tunnel called "Harry", as Blythe did, nor went blind, nor was shot on the run, as Blythe is. Nevertheless the film's jaunty celebration of rebellion, with its stirring distinctive music, and exhilarating emphasis on Hilts, the irrepressible American played by Steve McQueen largely on a motorbike, lies at odds with Cassie's experience.

"I don't look back with pride at our escape, but with great sadness," he said at a reunion at the Imperial War Museum in London in 2004. "This is the first time I have seen many of my former friends in 60 years. Being here today brings a lump to my throat because so many of my good friends were shot by the Gestapo."

The escape of 76 men on the night of 24 March 1944 from Stalag Luft III, the Luftwaffe's newly built high-security establishment at Sagan in Silesia, gave rise to one of the most notorious of war crimes when 50 recaptured men, including all four of Cassie's room-mates, were summarily shot on Hitler's orders. After the war the RAF spent three years investigating the affair and18 former Gestapo men were tried in Hamburg. Of those 14 were hanged in February 1948. In October that year three more were tried and two convicted of murder, but their sentences were commuted to life imprisonment.

Of the 76 escapers only three reached home. The other dozen not shot were brought back to the camp. Cassiedid not join the escape because he ould not overcome feelings of claustrophobia at going down the narrow,340ft tunnel pit-propped through crumbling sand.

He and his fellow forgers had spent months making 400 fake German documents in preparation for the break-out. One document could take five hours a day for a month to produce. The unit, led by Tim Walenn, started work in hut 120 in the north camp, moved to the kitchen block, then to the church room in hut 122, the scene of Cassie's lecture, and lastly to the library in hut 110. It was code-named "Dean and Dawson" after a London travel agency.

Cassie, a distinctive character with a shock of ginger hair and beard, made printing ink from fat-lamp-black mixed with oil, and ran off foolscap travelpermits on a tiny printing press made of a carved piece of wood covered with a strip of blanket. Some passes were made with the help of a "tame" prison guard whose wife in Hamburg typed the stencil and sent it back to him to give to the forgers.

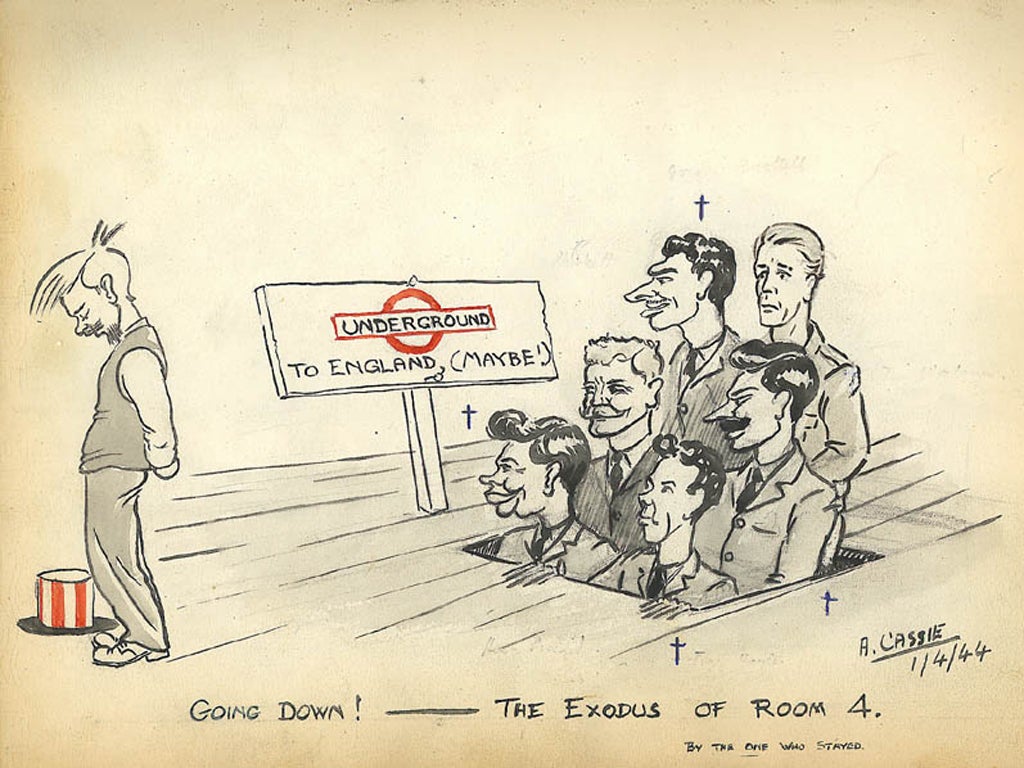

Cassie's fellow Stalag Luft III prisoner Paul Brickhill says in his book The Great Escape (1950): "The forgers worked till their heads were splitting and the points of their nibs and brushes and the letters they were forging seemed to jump and wiggle and blur under their eyes." They sat as close to windows as they could and worked mainly by daylight. Cassie also helped to produce 4,000 maps. He took charge of the forgery unit in March 1944 after Walenn (one of the 50 to die) joined the escapers. Cassie's heartfelt cartoon of his friends entering the tunnel, and of himself left behind, alludes to the London Underground, and the prisoners called the stopping-points for getting on and off trolleys inside it "Piccadilly Circus" and "Leicester Square".

Cassie had been a prisoner since being shot down on 1 September 1942 while flying a Whitley bomber with 77 Squadron on anti-submarine patrols from RAF Chivenor in Devon as part of Coastal Command. He remained in captivity until the war in Europe ended.

The forgers increased output as the day of the escape approached, and in the last few hours put the date on their whole year's work with a stamp made from a rubber boot-heel and distributed the varying papers and chits each man would need. Thirty-seven men fooled examining officials on trains with these forged papers despite a regime of four-hourly searches by the Gestapo. Some reached Berlin, Munich, the Danish border, and stations in Czechoslovakia. One of the three who reached Britain saw genuine papers faulted, but, travelling all the way to the Netherlands, had no trouble with his fake ones.

Alexander Cassie, the son of Scottish parents, was educated at Queenstown School in Cape Province, South Africa, and Aberdeen University, where he studied psychology and graduated in 1938. He joined the Royal Air Force in 1939. Of his art skills, he told theAberdeen Press and Journal in 2000:"I always had a pencil in my hand and had always been a competent artist and used to do covers for the university rag magazine."

After the war he became a military psychologist, rising to be a senior principal psychologist with the Army Personnel Research Establishment at Farnborough, Hampshire, before retiring in 1976. The work included interviewing aircrew to ascertain their suitability to fly. In 1973 he was listed as a Fellow of the British Psychological Society. Cassie, who raised his family at Cobham, Surrey, was a member of Oxshott Arts and Crafts Society and gave lessons in watercolour painting.

Alexander Cassie, RAF officer and psychologist: born 22 December 1916 Cape Province, South Africa; married Jean Stone (one son, one daughter); died Surrey 5 April 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks