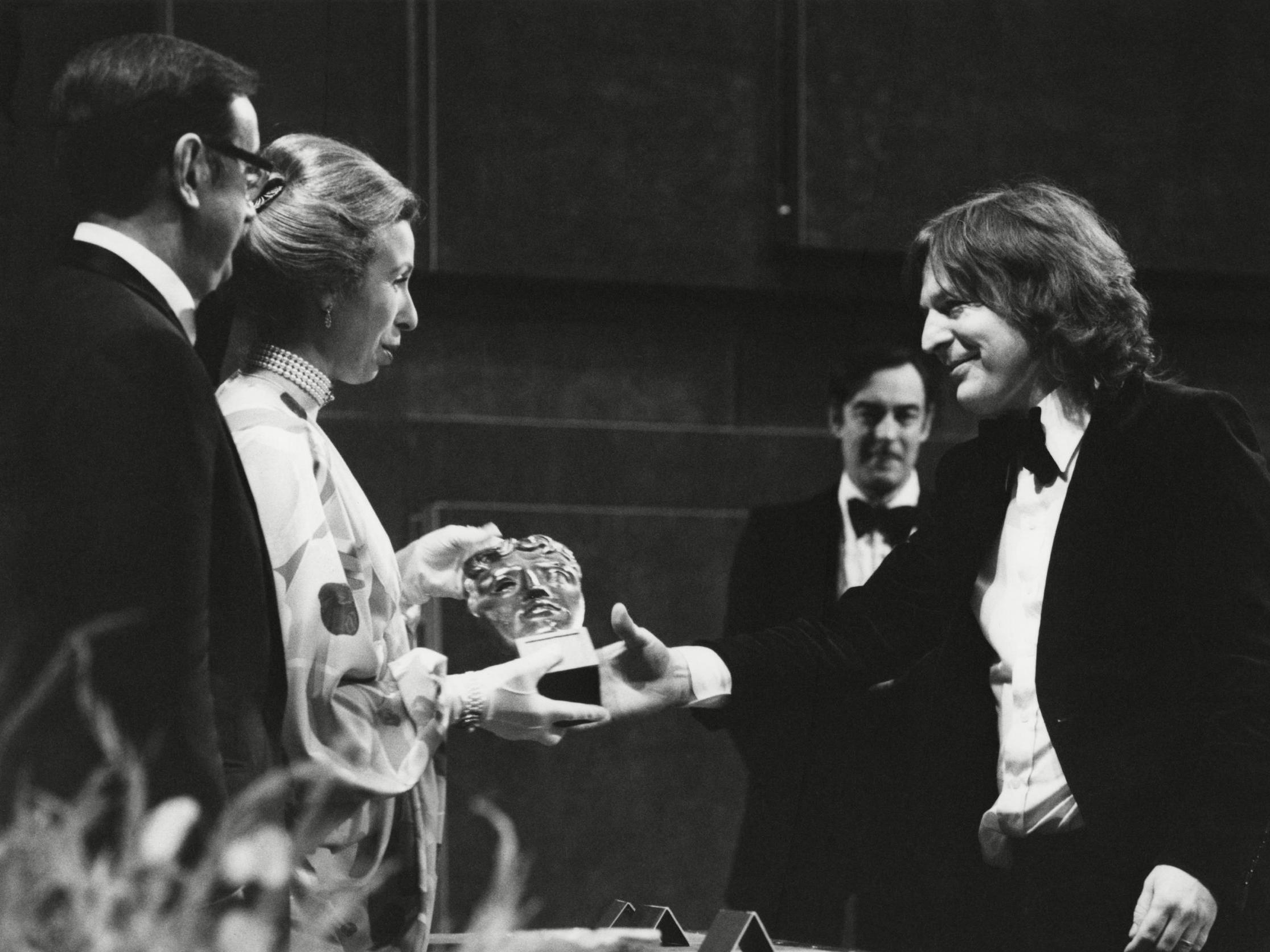

Alan Parker: Director of ‘Bugsy Malone’ and ‘The Commitments’

His films were described as ‘powerful but flawed’, often receiving mixed reviews but rising in critical esteem over time

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Alan Parker’s wildly eclectic films included a gangster musical with child actors (Bugsy Malone), a grim account of prison life (Midnight Express) and an upbeat tale of Dublin teenagers starting a soul band (The Commitments).

The director died on 31 July in London. He was 76. The British Film Institute announced his death, citing an unspecified illness.

Parker began his career in advertising, producing print ads and television commercials that formed his apprenticeship as a director. He made 14 feature films in his career, seldom venturing down the same cinematic path twice.

He received two Oscar nominations for best director, first for 1978’s Midnight Express about an American serving a prison sentence in Turkey, then 10 years later for Mississippi Burning, about an FBI investigation of the murders of three civil rights workers in 1964. (He lost to Michael Cimino, the director of The Deer Hunter at the 1979 Oscars and to Barry Levinson in 1989 for Rain Man – a job Parker had turned down.)

Along with dark dramas about social issues, Parker made a wide range of other films, including Bugsy Malone (1976), a lighthearted romp with an all-child cast portraying 1920s mobsters, featuring a 12-year-old Jodie Foster as a satin-gowned nightclub chanteuse; Fame, a 1980 movie musical about students at a New York performing arts high school; Shoot the Moon, a 1982 domestic drama about a disintegrating marriage, with Albert Finney and Diane Keaton; Pink Floyd: The Wall, a 1982 dramatisation of a concept album by Pink Floyd; and Evita, a large-scale 1996 production of the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical, starring Madonna as Eva “Evita” Peron, the wife of dictatorial Argentine leader Juan Peron.

“I just think,” Parker told The New York Times in 1982, “that it would be incredibly boring to do the same kind of subject 20 times, or even to make films in the same place, when you’ve got the whole world to explore. Right from the beginning, I didn’t want to be pigeonholed.”

His films were often described, in one way or another, as “powerful but flawed”. They sometimes received mixed reviews, but they often rose in critical esteem over time.

Reviewers were baffled by Parker’s feature debut, Bugsy Malone, which included costumed children in sophisticated dance numbers and in scenes where they were drinking, driving pedal-powered cars and having gangland shootouts – with marshmallows and cream pies as ammunition.

Critic John Simon seethed in New York magazine that the film was “an indecency, an outrage ... Wholesome youngsters have been duped into acting like adults – stupid, brutal, criminal adults, at that”.

(Parker said he got the idea for the film from his nine-year-old son.)

With Midnight Express, Parker moved to an entirely different world, a brutal Turkish prison where a young American, played by Brad Davis, was serving a long sentence for drug trafficking. The film, with a screenplay by Oliver Stone, depicted the prisoner’s harsh ordeal in unsparing terms but created a backlash for showing Turkey in an unflattering light.

“One couldn’t help feeling that there was something profoundly, gratuitously nasty about its sensationalism,” critic Vincent Canby wrote.

Yet in 1984, when Parker released Birdy, about two psychically wounded Vietnam War veterans, Canby found the film “so good and intelligent and moving” that it might require an “upward reevaluation of all the work” by the “consistently idiosyncratic, not conventionally likeable” Parker.

In 1987, Parker continued with his unconventional and controversial approach to filmmaking with Angel Heart, a dark private-eye film starring Mickey Rourke and Robert De Niro. The film originally carried an adults-only X rating for a graphic sex scene between Rourke and Lisa Bonet, which Parker reluctantly edited to receive a more commercially viable R rating.

Mississippi Burning was one of the most popular films of 1988, but it was denounced by some for taking liberties with history and for focusing on two white FBI agents, played by Willem Dafoe and Gene Hackman, rather than on black civil rights activists.

Parker defended his vision – “It’s fiction in the same way that Platoon and Apocalypse Now are fictions of the Vietnam War” – while maintaining that the film’s deeper truth was its depiction of the United States’ enduring struggle with racial injustice.

“I think all films in a way are manipulative,” he told The Washington Post in 1988. “You have a point of view, you know what you want to say. It’s my responsibility – or my duty – to make that as powerful as possible.

“It’s about the racism that’s within all of us. And it’s around now.”

Alan William Parker was born on 14 February 1944 in London. His mother was a dressmaker, his father a painter for London’s electricity company.

At 18, Parker began working in the post room of a London advertising agency and soon became a copywriter.

“The great thing about advertising in Britain at that time, and now,” he told The Washington Post, “is that it’s very egalitarian. Advertising didn’t care where you came from.”

His first experience with filmmaking came by directing adverts.

“English television commercials were awful, so we used to do a lot of experimenting in the basement of the agency,” he told The Times in 1982. “The art director did the lighting, somebody else ran the tape machine, somebody else ran the camera. I was the only one who couldn’t do anything. So I had to say, ‘Action!’ which any idiot can do. Then I realised I could also say, ‘Cut!’ And one day I shouted at an actor, ‘No, no, that’s not what’s wanted!’ And everybody looked at me, and suddenly I was a director.”

Parker’s adverts were hugely successful, and he began to experiment with short films. He was the first of several prominent directors, including Ridley Scott and Adrian Lyne, to emerge from the British advertising world.

On a film set, Parker could be a not-so-benevolent dictator, rewriting scripts and asking his cast to work through the night.

“I’m not difficult for ego reasons or for desire of awards – but for the work,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1988. “I’m not making movies for 14 intellectuals at the Cinematheque in Paris. I’m making films that have to find a wide audience.”

Parker often said his favourite film was The Commitments, an adaptation of a Roddy Doyle novel about young Dubliners in love with 1960s soul music. He shot the film on location, auditioning more than 1,500 people for the 10 leading roles; most of the prominent parts went to amateurs.

The Commitments has become a cult favourite for its portrayal of music as one of the few creative outlets for poor people.

The most difficult film Parker worked on was Evita, which required several meetings with Argentina’s president at the time, Carlos Menem. When Menem refused to allow the crew to film at the country’s presidential palace, Parker invited Madonna to meetings with Menem to seal the deal. When Madonna sang “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” from the palace balcony, 4,000 Argentine extras watched from below.

Making Evita, Parker later said, was “like riding bareback on a crazed elephant strapped to a jet engine, whilst Madonna combs your hair with a razor blade”.

His first marriage, to Annie Inglis, ended in divorce. Survivors include his wife since 2001, the producer Lisa Moran-Parker; four children from his first marriage; a son from his second marriage; and seven grandchildren.

Among Parker’s other films were Come See the Paradise (1990), set in part in a US internment camp for Japanese Americans during the Second World War; Angela’s Ashes (1999), based on Frank McCourt’s autobiography about growing up in an Irish slum; and his final film, The Life of David Gale (2003), starring Kevin Spacey as an opponent of capital punishment who finds himself in prison, sentenced to death.

Parker served as chair of the British Film Institute and was the first chair of the UK Film Council, which provided funding to the British film industry. He was knighted in 2002. He also published several works of fiction and volumes of cartoons.

Throughout his career, he turned down several blockbuster films, including Roger Rabbit and a Batman movie that would have earned him a fortune.

“I seem to always go against the grain,” he told the Chicago Tribune in 1991, citing a scene in Midnight Express, in which the American prisoner in the Turkish prison walks in the opposite direction of others in the exercise yard.

“That’s a lot like me,” Parker said. “I’ve spent my whole life walking in the opposite direction of everybody else.”

Alan Parker, filmmaker, born 14 February 1944, died 31 July 2020

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments