Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga: Civil rights champion who sought redress for Japanese Americans interned during World War Two

Among 120,000 people were displaced and sent to camps by the US during the war simply because of their Japanese heritage. Herzig-Yoshinaga’s diligence put a dark chapter of American history on record and led to reparations for those affected

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was a fortuitous discovery but it revealed much about one of America’s greatest wartime scandals.

Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, who died aged 92, had spent countless days trawling through public archives, seeking to understand the ins and outs of the forced relocation and internment of Japanese Americans during the Second World War. But this document, found perchance on an archivist’s desk in the autumn of 1982, was her most important discovery yet: it would prove that, after Pearl Harbor, the US mistreated large numbers of West Coast residents, purely because of their Japanese heritage.

So revealing of the US government’s constitutional failings was the document – titled Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast 1942 – that John McCloy, assistant secretary of war, ordered all 10 copies of it burnt after reading it. Neither McCloy nor, apparently, anyone else was aware that a copy had survived censorship. That was the one Herzig-Yoshinaga unearthed 40 years later.

Herself interned as a teenager during the war, Herzig-Yoshinaga dedicated much of her later life to revealing the racial discrimination she and some 120,000 others endured at the hands of the state she called home. Her research and activism, at first conducted in the shadows, then more publicly, made her a primary force in the struggle for recognition and redress.

That campaign culminated in the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which stated that the US government’s wartime actions against Japanese Americans derived from “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership”, and furthermore granted reparations to those who had been interned.

It was a victory for Herzig-Yoshinaga and the broader Japanese American community. But she always felt the US should have made greater amends for the harm it had caused.

Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga was born in Sacramento, California, in 1924, of parents who had emigrated from Kumamoto, Japan, five years earlier.

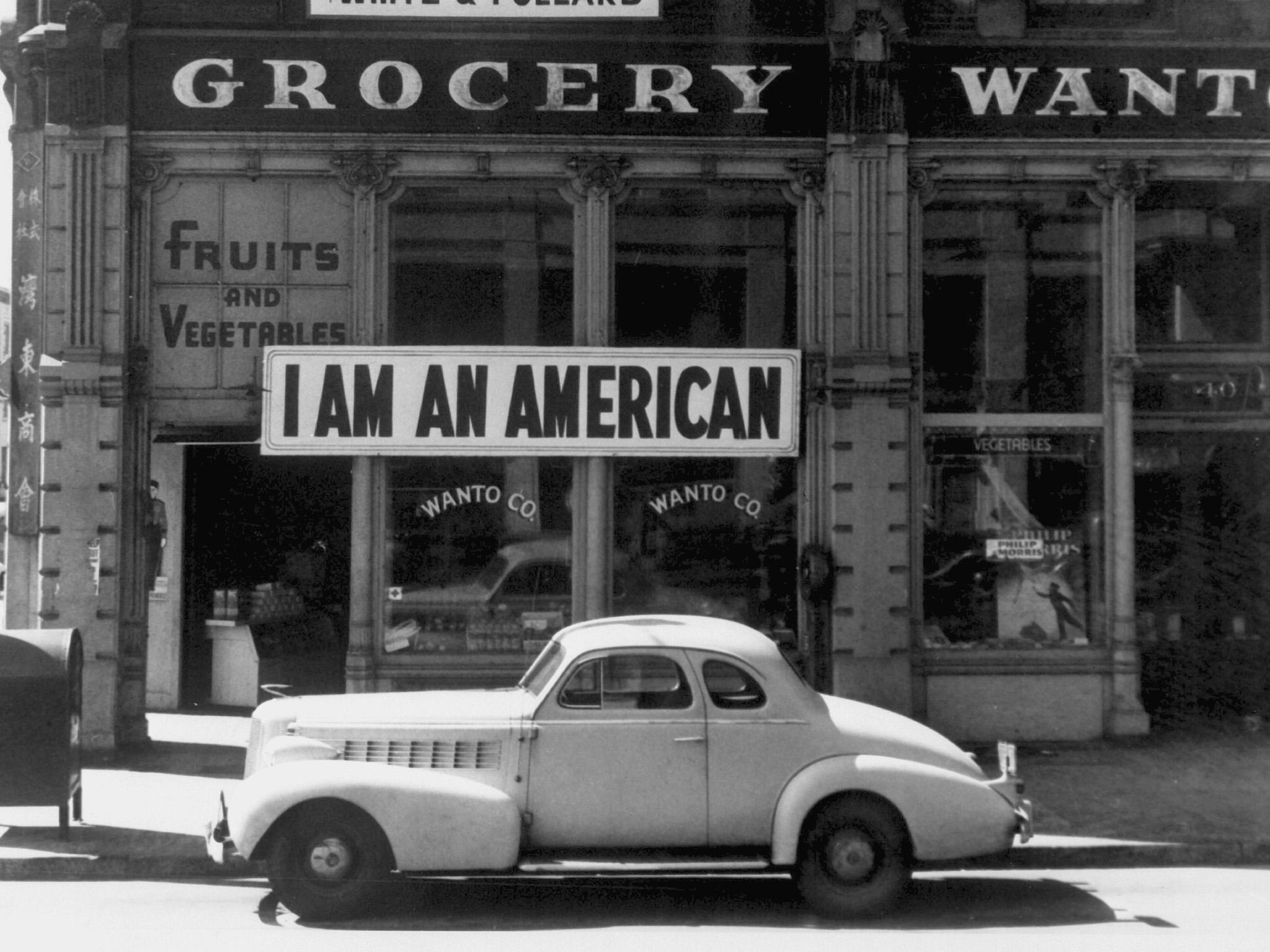

Racial boundaries were stark in pre-war Los Angeles, where she grew up, and while most of her schoolmates were white, virtually all of her friends were nisei – “second generation” – Japanese Americans. Still, Herzig-Yoshinaga bathed in American culture: she went to church, tap danced, played baseball, and – this was cause for parental concern – met boys at parties. She spoke fluent English and little Japanese.

But in 1942 she had the painful realisation that many would always view her as a foreigner when her high school principal told her she did not deserve her diploma, because “your country bombed Pearl Harbour”.

For a time she hated Japan, blaming it for her poor treatment in the US. “I didn’t choose to be born Japanese,” she thought, “but here I am now because of what you did, Japan”.

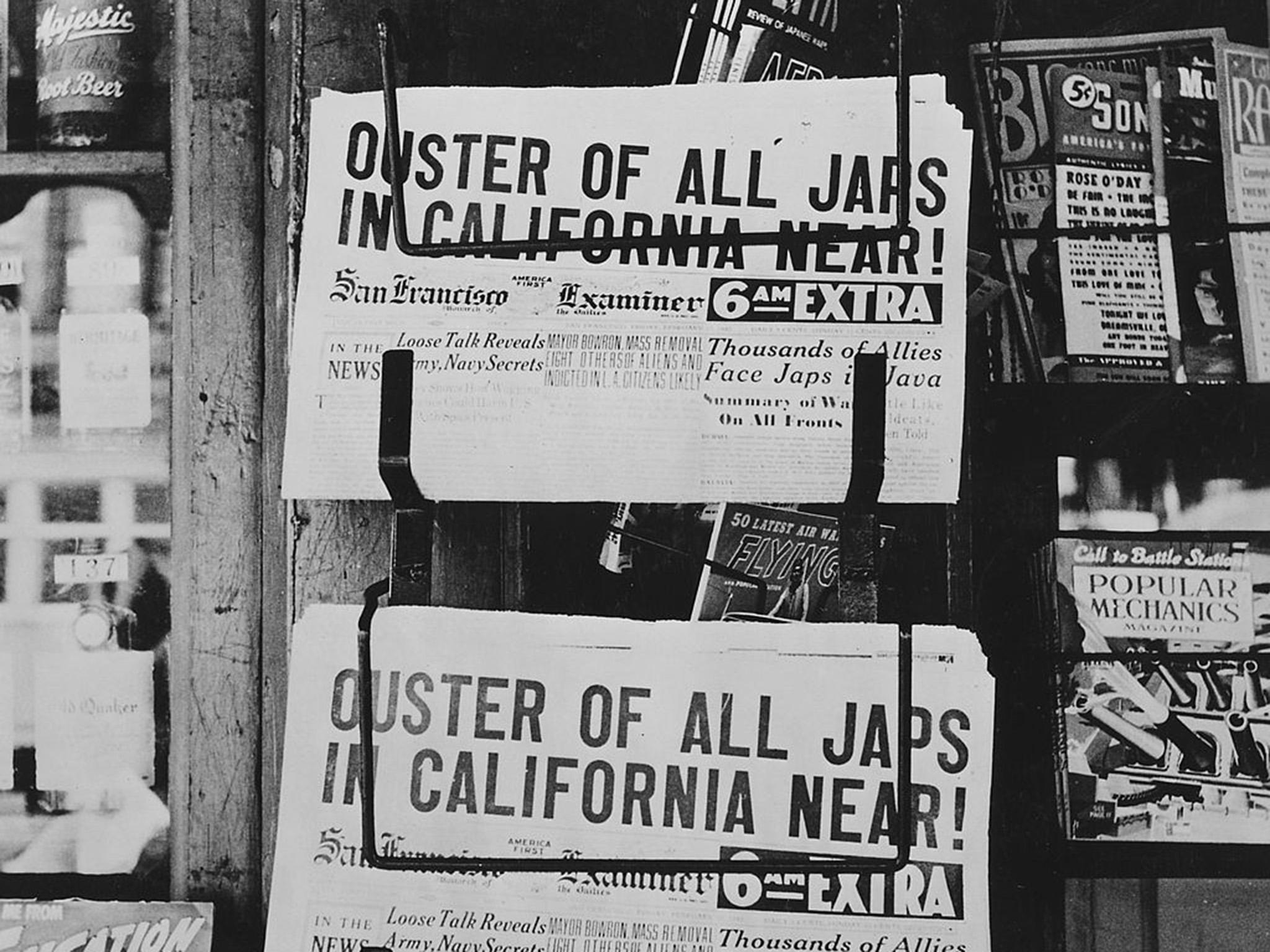

Matters quickly worsened after US President Franklin D Roosevelt signed an executive order allowing the military to exclude “any or all persons” from areas deemed strategically important. The military quickly used this new authority to target people whose family heritage linked them to the three Axis powers. By far the greatest number of victims were Japanese.

Widespread fear of a Japanese “fifth column”, stoked by newspapers as prominent as the Los Angeles Times and by countless politicians and army officers, served to justify the drastic measures.

In the midst of this collective hysteria, a 17-year old Herzig-Yoshinaga married her then boyfriend, Jake Miyazaki, fearing they might otherwise be separated. Together they were interned at the notorious Manzanar camp, in crammed barracks surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers. “It was desert,” she said of the camp. “Sagebrush and dust storms – every single day, dust storms. The first day, we were given a big sack, and told to go fill it up with hay. That was our mattress.”

During that time she bore their first child.

Upon her release in 1944, Herzig-Yoshinaga and her husband divorced. She was soon remarried – to Davis Abe, another nisei.

Abe, who worked in counterintelligence, was posted in Japan; she settled there with him for five years. It was her first time in the land of her parents and there too she found that she did not fit in: “I liked it very much, although I know I was treated like a gaijin [foreigner], because they could tell by the way I talked, or walked, or the way I dressed, I was not a Japanese-Japanese.”

During her union with Abe she had two more children, but the marriage eventually faltered. Soon after she moved to New York where she raised her three children alone, working as a clerk and office manager.

She had long avoided involving herself in political matters. But in New York, contact with the black civil rights movement of the 1960s and with Asian American activists awakened something in her. She was brought out of her shell and became a relentless and outspoken campaigner for recognition of the hardships she and her loved ones had endured.

In 1978, she retired and decided to dedicate her time, and clerking skills, to the study of public records on wartime exclusion and incarceration. She would come to read and catalogue hundreds of thousands of pages of documentation.

She was remarried that same year, this time to Jack Herzig. He would prove an invaluable collaborator, and emotional support, in her research.

In 1981, Herzig-Yoshinaga was appointed coordinator of research by the Congressional Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. The evidence she brought to light helped the commission conclude that military necessity did not justify the incarceration of Japanese Americans during the war.

Her discovery of the censored 1942 report was integral to the commission’s findings. The document also proved crucial in nullifying a key supreme court judgement from 1944, as it showed that the court had reached its ruling on false premises.

Written by the general who had largely implemented the West Coast displacement, it stated that it was impossible to determine the loyalty of Japanese Americans. All of them should be treated as foes, in his contention, without regard for due process.

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan acknowledged that the US had interned Japanese Americans without trial and without jury, purely on the basis of race. On signing into law the Civil Liberties Act, which he had initially resisted, Reagan said it would serve “to right a grave wrong”.

Herzig-Yoshinaga later worked for the Department of Justice’s Office of Redress Administration to help identify individuals eligible for redress payments, but she continued the fight – now to secure greater financial compensation than the $20,000 extended to each former detainee.

A documentary film about her, Rebel with a Cause, came out in 2016. That same year, she donated her collection of 33,000 documents to the University of California, Los Angeles.

Herzig-Yoshinaga is survived by her children Gerrie, from her first marriage, and Lisa and David, from her second marriage. Her third husband, Jack, predeceased her in 2005.

Still politically active into her eighties, Herzig-Yoshinaga encouraged others – and particularly women – to take up social justice issues. “I exhort you to go for it,” she said. In a reference to her own late start, she added: “Don’t let age deter you!”

As for the work that lay ahead, when asked in 2009 by a fellow Japanese American researcher what might yet advance their cause, Herzig-Yoshinaga replied, with typical verve: “I don’t think it’s really possible, but I really would like to see an international tribunal putting the United States on this, charging the United States, charging the United States for not living up to its democratic principles. Not just 9/11 and the aftermath of Guantanamo and all, but going back to our [Japanese American] situation.”

And she added: “Think that’s a dream?”

Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, Japanese American activist, born 5 August 1925, died 18 July 2018

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments