Agnes Varda: Filmmaker, feminist and pioneer of the French New Wave

She innovated the filmmaking style that informed the work of better-known contemporaries such as Godard and Resnais

Celebrated in Britain as a “playful visionary”, with films such as 1995’s La Pointe Courte and 1962’s Cleo From 5 to 7, French filmmaker Agnes Varda became known as the “grandmother of the French New Wave” – when she was barely 30 years old.

Her storytelling style – which she called cinécriture – broke with Hollywood and conventional European narrative structures, pacing and acting, paving the way for directors such as Jean-Luc Godard and Alain Resnais.

Following a career spanning more than 60 years, in 2017 Varda, who has died aged 90, became the first woman to win a lifetime achievement award at the Oscars. That year she made road trip documentary Faces Places, with the French photographer JR. The film was nominated for an Oscar last year.

Though she worked in the shadow of New Wave directors such as Godard, Resnais and Francois Truffaut, she was credited with inspiring many of the hallmarks of the movement: nonlinear narrative, an emphasis on mood over storyline and jump-cuts.

Varda was, by any definition, an outsider when she began making films in 1954: as a woman but also as a photographer, without professional training in cinema.

A former art and philosophy student, she spent her early career in Paris as the official photographer of the Théâtre National Populaire. Resnais, a friend who was making well-received documentary films, urged her to try filmmaking.

The French film production unions were hostile to amateurs, so Varda and a small crew working on a minuscule budget left Paris for the Mediterranean fishing village of Sète, where she lived as a child, to make La Pointe Courte.

Varda was determined to let the film’s narrative meander, without using dialogue as a vehicle for exposition. Though not a commercial success, critics noted its daring style.

Varda spent the next eight years making documentaries, several commissioned by the French tourism office. Her next feature was Cleo From 5 to 7, which she wrote and directed – the story of a female pop star suffering cancer.

A year later she made Salut les Cubains, a 1963 short documentary on daily life during the Cuban revolution told through thousands of still photographs. In 1967, she collaborated with directors including Godard and Resnais to make anti-war film Far From Vietnam.

Two years later, Varda made her American feature debut, Lions Love (… and Lies). The quirky and mostly improvised film starred the “Warhol superstar” Viva (Hoffman) and the authors of the rock musical Hair.

Arlette Varda was born in Brussels in 1928, to a Greek father and a French mother. Her family fled to Sète during the Second World War and she changed her first name to Agnès aged 18.

In 1962, she married director Jacques Demy, with whom she had a son. Earlier, she had a daughter with actor Antoine Bourseiller, and Demy adopted her.

Survivors include her children, Mathieu Demy and Rosalie Varda.

Varda’s interest in the feminist movement deepened in the 1970s. She made a short documentary about women, Réponse de Femmes (1975), and followed with several feminist-themed feature films.

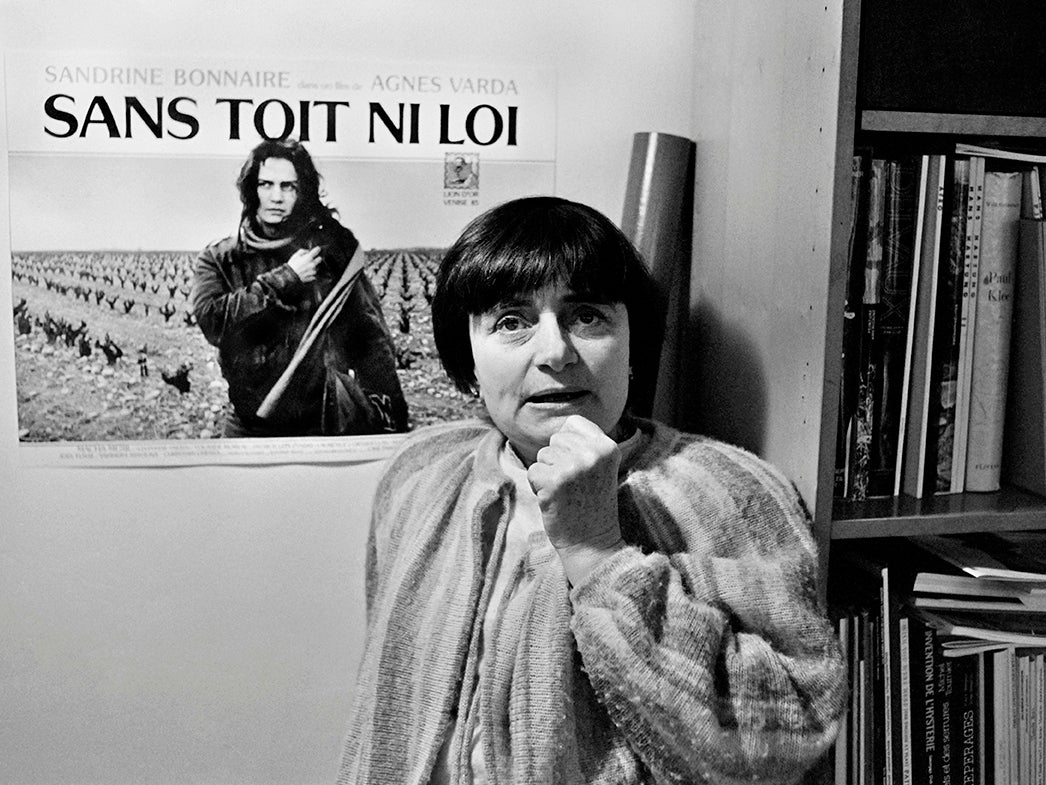

She won great acclaim as a feminist director with Vagabond, a 1985 drama about a drifter (Sandrine Bonnaire) whose body is found frozen in a ditch. Her story is revealed in flashbacks and semi-documentary-style interviews. The movie won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival.

In 1990, Demy died of complications from Aids. His death and her grappling with mortality became the subject of her 1991 documentary Jacquot de Nantes, which featured recreations of his early life and raw footage of him dying.

Varda made a second documentary about her husband, The World of Jacques Demy (1995), and one about herself, The Beaches of Agnès (2008). In 2015, she received an honorary Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, the first woman to achieve that award.

Her critically acclaimed 2000 documentary The Gleaners and I was a subjective documentary about French scavengers, but it became an extended exploration of Varda’s fascination with discarded or lost things.

“I am the queen of the margins,” she told The New York Times in 2009, reflecting on her lack of fame. “But the films are loved. The films are remembered. And this is my aim – to be loved as a filmmaker because I want to share emotions, to share the pleasure of being a filmmaker.”

Agnes Varda, filmmaker, born 30 May 1928, died 29 March 2019

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks