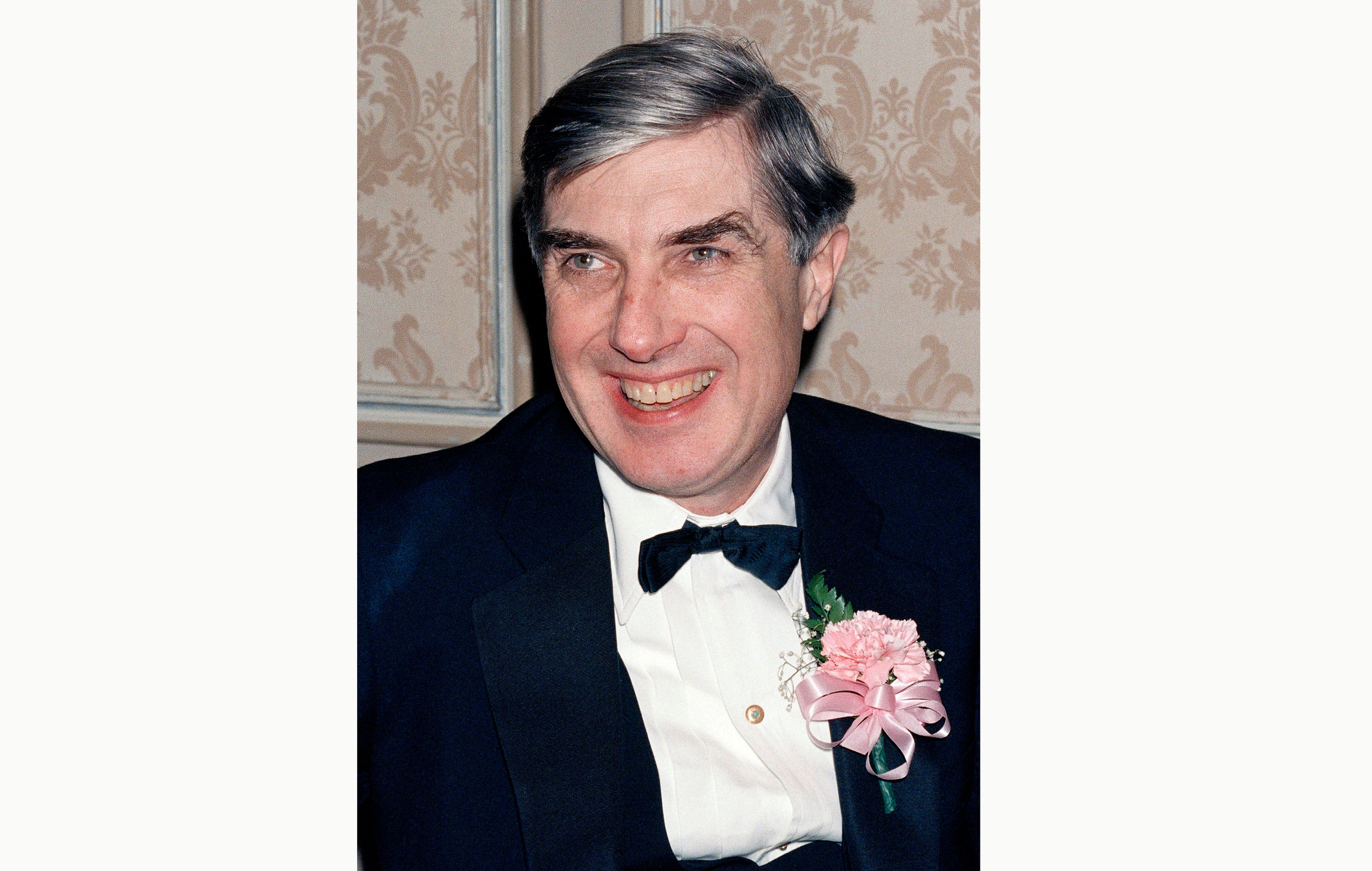

Neil Sheehan, Pentagon Papers reporter, Vietnam author, dies

Neil Sheehan, a reporter and Pulitzer Prize-winning author who broke the story of the Pentagon Papers for The New York Times and who chronicled the deception at the heart of the Vietnam War in his epic book about the war, has died

Neil Sheehan, a reporter and Pulitzer Prize-winning author who broke the story of the Pentagon Papers for The New York Times and who chronicled the deception at the heart of the Vietnam War in his epic book about the war, died Thursday. He was 84.

Sheehan died Thursday morning of complications from Parkinson's disease, said his daughter, Catherine Sheehan Bruno.

His account of the Vietnam War, “A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam,” took him 15 years to write. The 1988 book won the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction.

Sheehan served as a war correspondent for United Press International and then the Times in the early days of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War in the 1960s. It was there that he developed a fascination with what he would call “our first war in vain” where “people were dying for nothing.”

As a national writer for the Times based in Washington, Sheehan was the first to obtain the Pentagon Papers, a massive history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam ordered up by the Defense Department. Daniel Ellsberg, a former consultant to the Defense Department who had previously leaked Vietnam-related documents to Sheehan, had copied the papers and made arrangements to get them to Sheehan.

The Times’ reports, which began in June 1971, exposed widespread government deception about U.S. prospects for victory. Soon, The Washington Post also began publishing stories about the Pentagon Papers.

The Pentagon Papers looked in excruciating detail at the decisions and strategies of the war. And they told how involvement was built up steadily by political leaders and top military brass who were overconfident about U.S. prospects and deceptive about the accomplishments against the North Vietnamese.

Soon after the initial stories were published, the Nixon administration got an injunction arguing national security was at stake, and publication was stopped. The action started a heated debate about the First Amendment that quickly moved up to the Supreme Court. On June 30, 1971, the court ruled 6-3 in favor of allowing publication, and the Times and The Washington Post resumed publishing their stories.

The Times won the Pulitzer Prize for public service in 1972 for its Pentagon Papers coverage, and the paper’s editors praised Sheehan for his central role.

“We are all particularly proud of Neil Sheehan for the tenacity, knowledge and professional ability that contributed so pivotally to the whole project,” said A.M. Rosenthal, then the managing editor of the Times, after the Pulitzer was announced.

The Nixon administration tried to discredit Ellsberg after the documents’ release. Some of President Richard Nixon’s top aides orchestrated the September 1971 break-in at the Beverly Hills office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist to find information that would discredit him. The White House called the secret unit the “plumbers,” since its role was to stop leaks.

For leaking the Pentagon Papers, Ellsberg was charged with theft, conspiracy and violations of the Espionage Act, but his case ended in a mistrial when evidence surfaced about government-ordered wiretappings and break-ins.

After the publication of the Pentagon Papers stories, Sheehan became increasingly interested in trying to capture the essence of the complex and contradictory war, so he set out to write a book.

“I tried to tell the story of what happened in Vietnam, and why it happened,” he said in a 1988 interview that aired on C-SPAN. “The desire I had is that this book will help people come to grips with this war. ... Vietnam will be a war in vain only if we don’t draw wisdom from it.”

Sheehan thought his book about the war could be best told through his account of an officer he had met in Vietnam. John Paul Vann was a charismatic lieutenant colonel in the Army who served as a senior adviser to South Vietnamese troops in the early 1960s, retired from the Army in frustration, then came back to Vietnam and rejoined the conflict as a civilian helping direct operations in a variety of roles.

Vann was convinced the U.S. could have won the war if it had made better decisions. To Sheehan, Vann personified the U.S. pride, the confident attitude and the fierce will to win the war — qualities that clouded the judgment of some on whether the war was winnable.

Former Secretary of State John Kerry, a Vietnam veteran, told an audience at a 2017 screening of a Vietnam documentary that he never understood the full extent of the anger against the war until he read “A Bright Shining Lie,” which showed him that all the way up the chain of command “people were just putting in gobbledygook information, and lives were being lost based on those lies and those distortions,” according to a New York Times account.

The war had a deep effect on Sheehan’s outlook.

“It transformed my thinking and I think the thinking of my whole generation,” Sheehan told The Harvard Crimson in a 2008 interview. “We believed in authority figures and what they told us. And it turned out they were wrong or lying to us.”

Once Sheehan launched into the project, the intense and driven writer found it dominated his life.

“I was less obsessed than I was trapped in it,” he said. “I felt a great sense of being trapped.”

Neil Sheehan was born Oct. 27, 1936, in Holyoke, Massachusetts, and grew up on a dairy farm. He graduated from Harvard, and worked as an Army journalist before joining UPI. After he left Vietnam, he worked for the Times in Washington as a Pentagon reporter and later at the White House, before leaving the paper to write his Vietnam book.

Early in the research for “A Bright, Shining Lie,” Sheehan was involved in a near head-on car crash that broke multiple bones and put him out of action for months, but writer friends urged him to continue his book project.

He and his wife, Susan, a writer for The New Yorker, sometimes struggled to make enough money to pay the family’s bills while he was working on the book. He combined fellowships with occasional advances from his publisher to get by.

Sheehan wrote several other books about Vietnam, but none with the ambitious sweep of “A Bright Shining Lie.” He also wrote “A Fiery Peace in a Cold War” about the men who developed the intercontinental ballistic missile system.

Susan Sheehan won a Pulitzer Prize in 1983 for general nonfiction for a book on the crippling effects of mental illness.

The couple had two daughters, Catherine Bruno, and Maria Gregory Sheehan, both of Washington and two grandsons, Nicholas Sheehan Bruno, 13, and Andrew Phillip Bruno, 11.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks