Review: Hardcore rocker dials it down on mature solo project

Sometimes it takes a crisis to settle into the space you should have been all along, writes Scott Stroud of The Associated Press

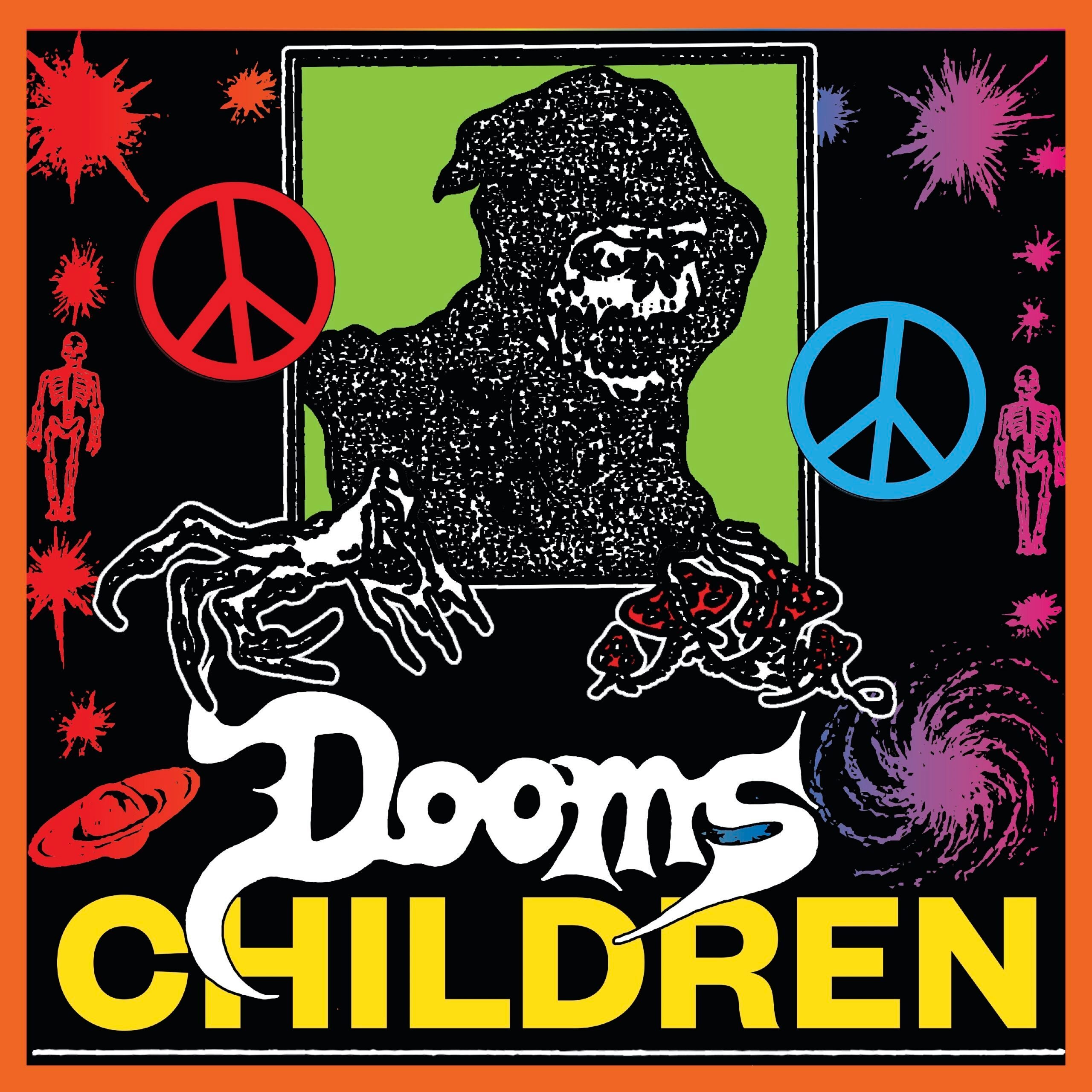

“Dooms Children" by Dooms Children (Dine Alone Records)

Sometimes it takes a crisis to settle into the space you should have been all along.

That appears to be the case on “Dooms Children," the new solo project by Wade MacNeil, who made his name fronting hardcore bands such as Alexisonfire and Gallows. His new venture, which he describes as “a record about my life falling apart and then trying to pick up the pieces," shows more maturity than the rocket-propelled ferocity of his earlier work.

What you're left with are 11 power rock ballads that make up for the drop in ferocity with stronger melodies, more introspective lyrics and better playing. There's no loss of intensity in songs like “Psyche Hospital Blues" and “Heavy Year," which begins with a meditation on the death of MacNeil's mother, and the amps aren't turned down much. But the energy feels more directed and constructive.

The best achievements here are slower songs like “Flower Moon" and “Skeleton Beach," which give themselves room to breathe. That allows MacNeil's sandstone-gravel voice to convey genuine regret. Something similar happens on “Morningstar " which begins with a 90-second instrumental opening before winding deliberately into an optimistic, shine-again message.

There are a few trite turns here. A power love ballad called “Spring Equinox is built around the hook, “You don't need no sugar; you're sweet enough to me." And some of the songs devolve into the insert-guitar-solo-here sensibility of a long-ago era that has been worked over pretty good — think Blue Oyster Cult with bigger amps.

But the sentiments are heartfelt and the music has real power. MacNeil has preserved the intensity of his earlier work even as he relinquishes just enough of its frenzy to find the place where he belongs.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks