How the Leveson Report stopped the press in its tracks: One year on, the forensic cataloguing of media bullying retains its power to shock

It's a year since Lord Justice Leveson delivered his verdict on British newspapers. The implications are still sinking in, says Andreas Whittam Smith

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

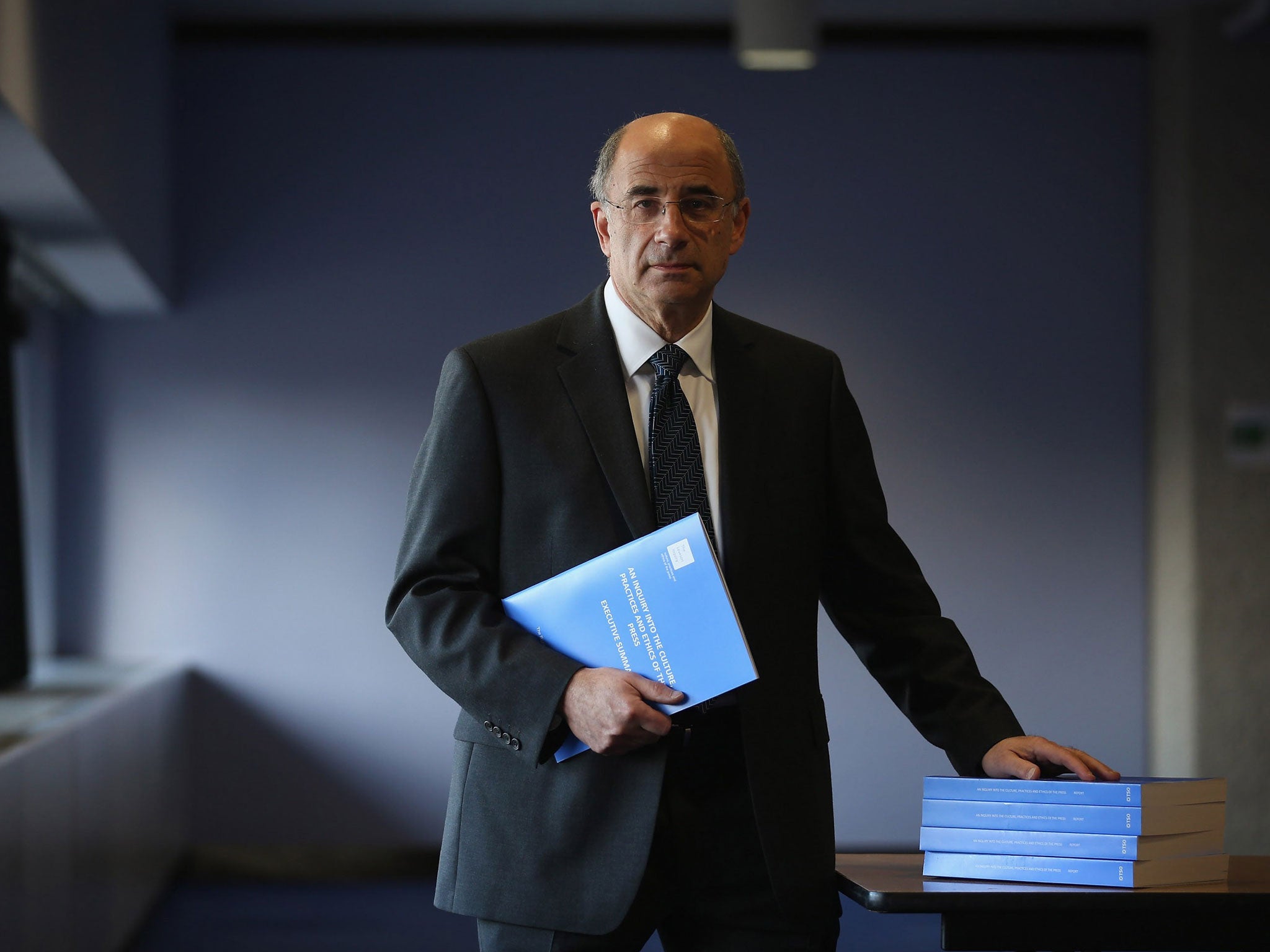

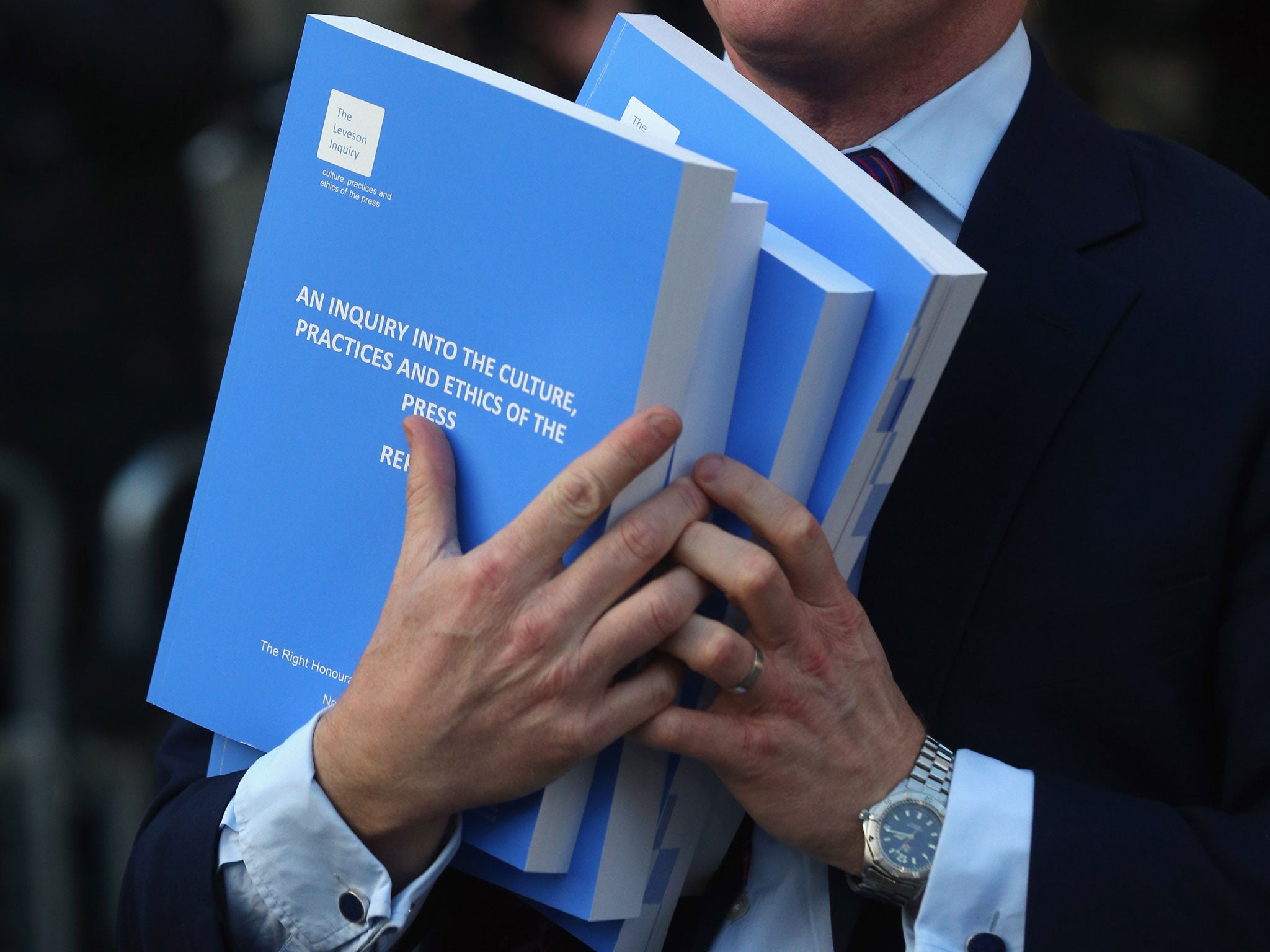

Your support makes all the difference.Today is the first anniversary of the publication of a very important report that hardly anyone has read. It is Lord Justice Leveson's Inquiry into the Culture, Practices and Ethics of the Press. As the report weighs over 9kg and comprises nearly 2,000 pages, the media was forced in the time available on the day to rely upon a summary. That done, the four volumes seem to have since been placed on high shelves and forgotten. I would be surprised if more than 100 people have read every word. At least I have now turned every page.

But the report's influence on British life has been out of all proportion to its readership. Not one but two charters for a new press regulator have now been put to the Privy Council. According to the report's critics, its proposals herald the end of more than 300 years of press freedom – even though Lord Justice Leveson was at pains to insist that this was not the case. According to its backers, its recommendations are overwhelmingly supported by the public – even though it seems unlikely that many people know precisely what they are.

In the coming week, national newspapers are under pressure to decide whether to align themselves with the Independent Press Standards Organisation (Ipso) – the body that the industry has set up in defiance of the Royal Charter backed by all three main political parties – or to seek some other response to the threat, if they do not sign up to the Royal Charter, of having to pay potentially ruinous exemplary damages.

Yet reading through the report today one is left with the impression not of a remaking of the regulatory landscape but, overwhelmingly, of the misery and distress caused over many years by newspapers' invasion of privacy, even when there was not a shred of public interest.The report gives many examples.

Sienna Miller, not knowing that her phone was being hacked, was led falsely to accuse close family members and friends of leaking stories to the press. Max Mosley expressed the belief that the constant, unflattering and unpleasant coverage of him was a contributing factor in the suicide of his son. In a similar case, Margaret Watson set out her conclusion that inaccurate and partial reporting of the murder of her daughter, Diane, contributed significantly to the suicide of her son, Alan, who was unable to cope with the unsubstantiated allegations levelled at his dead sister.

Then there are the notorious incidents involving the Dowlers, the McCanns and the wrongly arrested Christopher Jefferies. When the Dowlers decided one day to walk home from Walton-on-Thames railway station following the route that their missing daughter, Milly, habitually took, they intended it to be an intensely private moment. But, forewarned, the News of the World had stationed a photographer with a long lens somewhere along the route. The newspaper published a picture the following Sunday: "Face etched with pain, missing Milly's mum softly touches a poster of her girl as she and her hubby retrace her last footsteps." So much for privacy.

Of the McCanns, the report observes: "They had become a news item, a commodity, almost a piece of public property where the public's right to know possessed few if any boundaries." The completely innocent Christopher Jefferies told the Inquiry that "the tabloid press had decided that I was guilty of Ms Yeates' murder and seemed determined to persuade the public of my guilt".

Editors and journalists in the popular press dare not allow themselves to dwell on the harm that their invasions of privacy can cause. Otherwise they would not be able to do the job they have set themselves. For they serve a large market of newspaper buyers who relish gossip about people in the news whether they are stars of entertainment or sport, or members of the Royal Family, or just ordinary people like the Dowlers or the McCanns, who have got caught up in dreadful events. This is not the serious journalism that these newspapers also do, such as the Mail on Sunday's exposure of Reverend Paul Flowers' performance as chairman of the Co-op Bank, but entertainment.

In effect, celebrities become unofficial members of the families of newspaper readers or of their circles of friends. We like to hear about them, and so we ask each other: "Did you see that Charles and Camilla have been to Sri Lanka for some meeting or other?" It is as if Charles were one's uncle or Camilla one's aunt. I did this myself on Wednesday morning when I asked my wife if she had seen what Charles Saatchi had alleged about his former wife, Nigella Lawson. We don't know them, but we think we do. This appetite for gossip is fact. You cannot wish it away.

Magazines (and websites) also meet this demand, so that is where newspaper readers would go if newspapers suddenly stopped providing this sort of coverage. In this light, the discovery by journalists of the techniques of phone hacking seemed like a gift. It provided strong stories and didn't seem a terribly wrong thing to be doing. Phone hacking was seen as a brilliant, uncontroversial technique.

Except that it wasn't only that. It was illegal, it invaded privacy in a particularly surreptitious manner, and it magnified the hurt and harm that newspapers cause when they write about people's private lives.

As the Leveson report relates, the practice suddenly became public by chance. In December 2005, the Royal Household told Scotland Yard that they were concerned that the voicemail messages of the private and personal secretaries to Princes William and Harry had been unlawfully intercepted. Information published by the News of the World in Clive Goodman's column suggested knowledge of the content of voicemail messages left on their mobile phones. The police decided to investigate phone hacking for the first time – perhaps because it involved the Royal Family.

By August 2006, they were in a position to arrest Clive Goodman and Glen Mulcaire, a private investigator who worked for the News of the World. Police searches had generated suspicions that Mr Mulcaire's work was centred on obtaining access to voicemails, mainly for the News of the World in return for substantial cash payments. Mr Goodman and Mr Mulcaire went to trial and were found guilty. They were sentenced to four and six months respectively. Much more might have been discovered implicating the press, but the police operation was prematurely shut down. Scotland Yard pleaded shortage of resources and better things to do.

The same thing happened to another line of inquiry. In 2001, the Devon & Cornwall police were investigating an allegation of blackmail in Plymouth. A member of the public had obtained details of the criminal convictions of someone else. It turned out that an officer serving with the same force had accessed the Police National Computer record of the victim. It looked as if he had passed the information on to private investigators working for the alleged blackmailer.

As their inquiries progressed, the police discovered a network of investigators, in the main retired police officers, who were sourcing on demand information from police employees or from other agencies such as the Department for Work and Pensions. This investigation led to, among others, a particular private investigator, Steve Whittamore. The police searched his premises. In detailed ledgers, they found invoices to journalists setting out what information was sought and the fee.

This was also a matter for the Information Commissioner, who is guardian of Data Protection, with powers to prosecute. Inexplicably, however, the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) never got as far as even interviewing any journalist to see whether there was a case for bringing criminal charges. A former senior official at the ICO told Lord Justice Leveson why he thought nothing had been done. He said (although others at ICO disputed his interpretation) that the decision "not to pursue any journalist was based solely on fear – fear of the power, wealth and influence of the Press and the fear of the backlash that could follow if the press turned against the ICO".

There was a third important institution that dropped the baton, the Press Complaints Commission (PCC). Given its role, this was the most serious failure of all. As Leveson observes, there was no reason why the PCC should not have investigated allegations of phone hacking. Indeed, it made two attempts, one in 2007 and another in 2009. In both reports, the PCC concluded that there was no evidence that phone hacking was widespread. And in 2009, observed Leveson, "there was the additional feature of the belittling of those who were contending that hacking was widespread".

We have arrived at an important point in the story. As the Leveson Report makes plain, three institutions that might have gripped the scandal of phone hacking at an early stage failed to do so. After Scotland Yard had dealt with Mr Goodman and Mr Mulcaire, it lost interest. The Information Commissioner never got started. And the PCC had a go but missed the point.

What explains these failings? The report never quite pins this down, but one explanation is that the press as a whole seemed too powerful to attack. As Leveson puts it: "The press are in a unique position as they carry a very large megaphone; if people cooperate, that megaphone can be used to enhance careers: for those who complain or challenge titles, the megaphone can be used to destroy them."

It is worth noting, in this context, that lawyers bringing claims against News International (publisher of the Sun, the News of the World, The Times and the Sunday Times) were subjected to ongoing surveillance "commissioned with a view to trying to force them to remove themselves from the litigation".

Today, however, the once-mighty newspaper industry is a wounded beast. Many journalists are facing criminal charges for corrupt practices of various kinds, including phone hacking. Indeed many of them have suddenly learnt what their victims must have felt: their life and their family's life ruined by the decisions of a seemingly impersonal institution, in this case the criminal justice system, as they pass anxious months waiting to learn whether they will go to trial or not and, if they do, how it will turn out.

Moreover, the Press Complaints Commission has been forced to throw in the towel. Lord Black, chair of the body that finances it, told the Inquiry that the existing system had lost the confidence of Parliament, of the public and of the judiciary… It had also lost the support of parts of the newspaper and magazine publishing industry. And the Prime Minister, David Cameron, told the House of Commons: "Let's be honest. The Press Complaints Commission has failed. In this case, the hacking case, frankly it was pretty much absent."

Lord Justice Leveson recommended that there should be a new press standards body created by the industry, with a new code of conduct. And that body should be backed by legislation, which would create a means to ensure that the regulation was independent and effective. Thus into the field have come two versions of a new regulatory body: the Government's Royal Charter proposal, and a popular press version that dispenses with any element of government participation. Three newspapers have largely stood aside from the wrangling between the Royal Charter proponents and the hands-off-our-press brigade: The Independent, The Guardian and the Financial Times.

It is an invidious choice for such newspapers to have to make. The Independent, for example, has struggled for all 27 years of its existence to produce ethical journalism. We have not always succeeded, but we have not hacked phones or harassed people or knowingly used paparazzi photographs or paid witnesses or suborned public officials. We have attempted to abide by our industry's Editor's Code and have acknowledged our failings in print.

Leveson's scrutiny of our working practices was (to put it politely) cursory. One of his statements about this newspaper was pasted in from a hoax Wikipedia entry. Yet now, thanks to his report, and the Crimes and Courts Act 2013 – enacted to create a mechanism by which Leveson's recommendations could be enforced – we, too, are faced with Leveson's Choice. We must decide whether to: wait for a regulatory body to emerge that complies with the Royal Charter (thus offering potential for state interference); defy the three main political parties, sign up to Ipso and risk exemplary damages – even arising from correct stories – that could put us out of business; or (my preferred option) choose neither route – but still face the same ruinous threat.

One year on, the Leveson Report retains its power to shock with its forensic cataloguing – based on the examination of more than 300 witnesses – of a culture of media bullying.

Yet its most shocking and lasting impact may yet turn out to be the damage it inflicts on the publications that have tried hardest to do the right thing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments