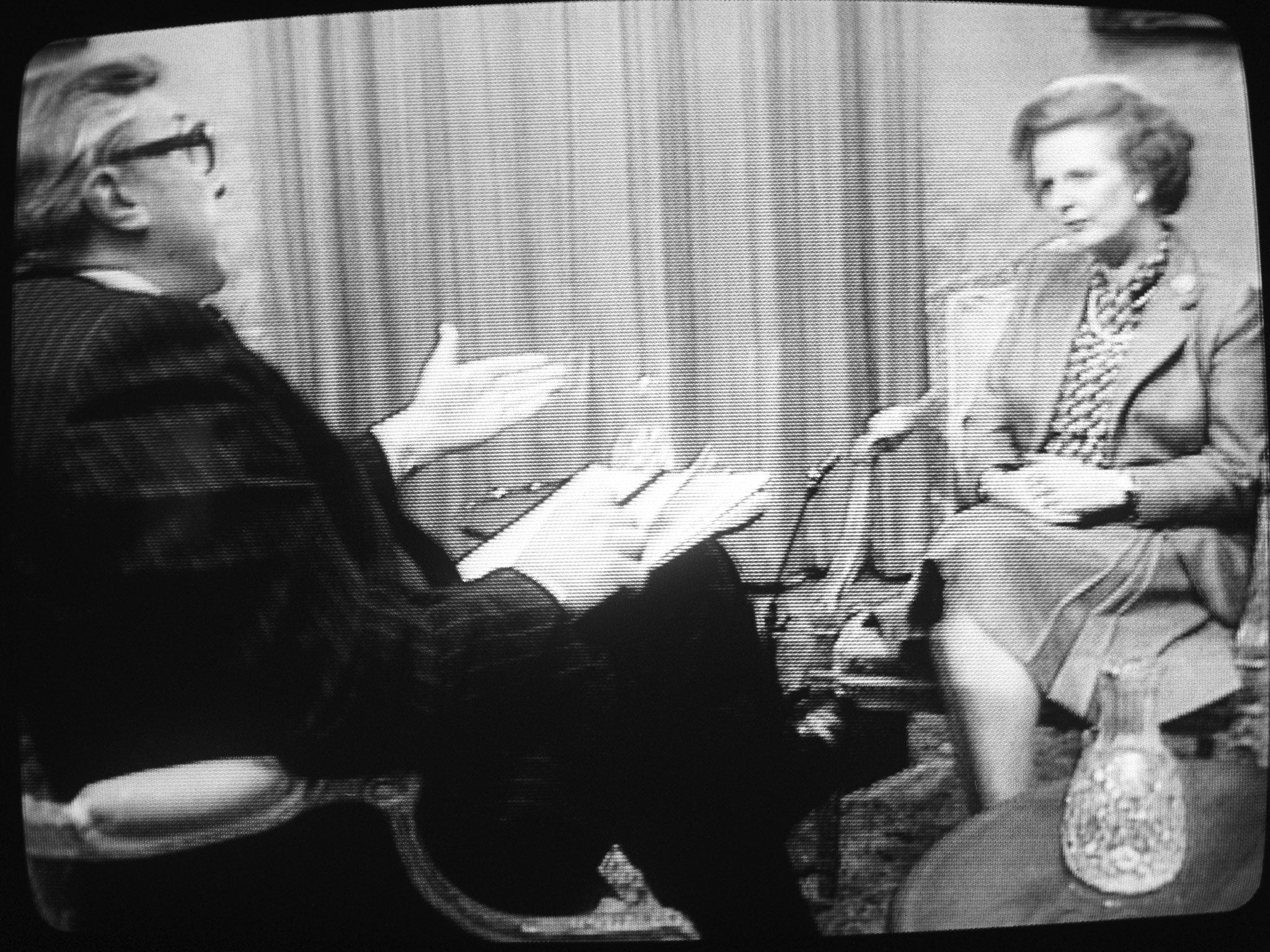

Ian Burrell: BBC survived Margaret Thatcher’s hostility but still faces political opposition

The Media Column

If BBC executives had any regrets about commissioning Hilary Mantel’s The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher for Radio 4’s Book at Bedtime, they will surely have been soothed by the latest revelations from Kew.

Files from the National Archive give us new insight into the antipathy of many political leaders for the BBC. Within months of becoming Prime Minister, Mrs Thatcher wished to force it to carry advertising and remove its unique position in the broadcasting spectrum.

She favoured undermining the licence fee by encouraging ITV to create television sets which received only commercial channels, giving viewers the opportunity to bypass the BBC. To Mrs Thatcher, the licence fee was “a compulsory levy on those who have television sets”.

The Prime Minister, who was persuaded to drop her plans following objections led by Willie Whitelaw, the Home Secretary, was concerned about “the extravagance of some of the BBC’s spending”. With the broadcaster then operating a £50m deficit, she had a point.

But the real motive for her tough stance is found in another memo released from Kew and written by the Number 10 policy unit about a 1985 review of BBC funding. The “unstated objectives” of this exercise were to “knock the BBC down to size” and prevent it “extravagantly expanding into everything”, including breakfast television.

The words are a striking reminder of the long and shocking history of British Governments seeking to curtail the influence of the BBC. New Labour, led by its confrontational communications chief Alastair Campbell, went to war with the organisation over its reporting of the Iraq war. The Hutton Inquiry whitewash did more damage to the corporation than anything the Tories have thrown at it.

The attacks continue. David Cameron’s criticisms of the BBC over its “Wigan Pier” coverage of the Autumn Statement can be seen in a broader context: departing Ofcom chief executive Ed Richards complained to this newspaper last week of the cosy relations between Government officials and Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp as it sought to outgun the BBC by taking full control of BSkyB. Mr Murdoch, along with Tim Bell and Maurice Saatchi, was among Mrs Thatcher’s great media allies. She had few friends at the BBC, though she was fond of Jimmy Young, the populist Radio 2 presenter.

The newly-released files show the resilience of the BBC in the face of political hostility. The plans by Thatcher’s strategists to bring the BBC “down to size” emphatically failed. They wished to prevent its extravagant expansion but the BBC is now free on every media platform and has the biggest website in the UK, to the chagrin of press publishers. It is the dominant player in breakfast TV, the sector Thatcher’s Government most wished to keep BBC-free (she was a friend and admirer of TV-am’s Bruce Gyngell, the pioneer of the genre).

This despite what even The Sunday Telegraph described as a “Tory vendetta against the BBC” during the Eighties. Douglas Hurd, the Home Secretary at the time, has since written of his alarm at a “growing obsession against the BBC”.

Mrs Thatcher was furious about a 1985 Real Lives documentary that gave a platform to former IRA commander Martin McGuinness – and the BBC’s governors pulled the programme under intense political pressure. Her attack dog, Norman Tebbit, was unleashed whenever the broadcaster was seen as less than a cheerleader for Britain and its allies, such as in coverage of America’s bombing of Libya in 1986.

The tensions were at their height during the Falklands War. The venerable Peter Snow (father of historian Dan Snow and then a reporter on Newsnight), was accused by a Tory MP of an “almost treasonable” act in noting the difficulty of corroborating British casualty figures. Mrs Thatcher said Snow’s use of the term “the British” caused “offence” and “great emotion”. When filmmaker Michael Cockerell made a Panorama featuring politicians with reservations about the war, Tory MPs tabled a motion accusing the BBC of “anti-British bias”.

It’s a little ironic that one of the BBC’s latest controversies has concerned its supposed jingoistic baiting of Argentina over the Falklands War during the recent Patagonia special of Top Gear.

The BBC survived Thatcher’s assault. She returned to her plan for an advertiser-backed BBC in the mid-Eighties only for the Peacock Committee to conclude that the idea would cripple ITV’s revenue structure.

Much has changed in 30 years. Audiences that watched Ministry of Defence spokesman Ian McDonald sombrely relaying details from the South Atlantic on the Nine O’Clock News had a relationship with the BBC not so dissimilar to those gathered round the wireless in the Second World War.

In the internet age the traditional media outlets are challenged by the public as well as politicians. The BBC has in the past year been the focus of angry protests over its coverage of the Scottish referendum and the conflict in Gaza.

It will face further political intimidation in the months ahead, as a frenzied pre-election climate precedes its next 10-year licence fee settlement. Despite its robust record in fighting off political opponents its future is far from guaranteed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks