The music industry's future may not depend on charging for songs

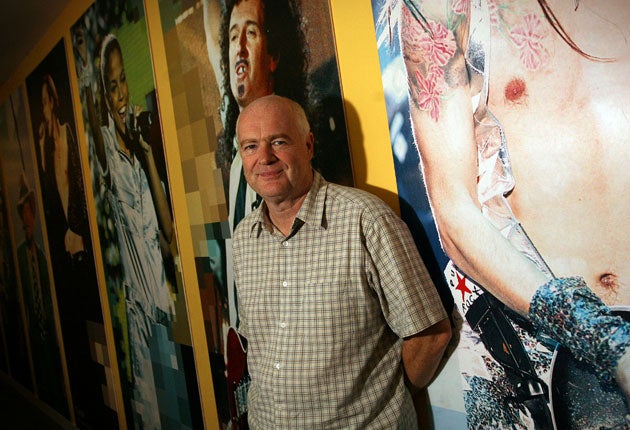

Tony Wadsworth ran EMI for a decade and is chairman of the British Phonographic Industry. He tells Ian Burrell about the changes the business must make in order to survive

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Tony Wadsworth was chairman and chief executive of EMI when Radiohead walked out of Britain's most famous record company and decided to start giving their material away for next to nothing – or as much as their fans were willing to pay for it.

But the famously genial Wadsworth doesn't bear a grudge. Rather, he admires Thom Yorke, Ed O'Brien and the boys for having shaken up the music industry and made it think more radically. "I thought what they did was very interesting and innovative because what it did was question the notion of how you derive value from music."

His magnanimity may be due to the fact that his primary role now is chairman of the British Phonographic Industry, meaning he is obliged to identify means of ensuring the future health of a business in which the this country continues to excel. The United Kingdom is the world's third largest music market (with 10% of world sales, behind only America and Japan) and had the highest purchase rate of CDs on the planet last year (at 2.2 per head).

But as the CD itself begins to feel archaic, the "biz" is having to change, and Wadsworth claims it already has. "I'm actually very optimistic about the future of music," he says, over a plate of risotto in an Italian restaurant close to London's Westminster Bridge. "It's the art form that most connects with human beings, without being too pretentious about it. The demand for and love of music is always going to be a key part of human behaviour."

Fine – but a whole generation of human beings are connecting to the art form without contemplating the purchase of a CD, declining to even make a micro-payment for a download when it's easier to take the tune for nothing.

According to Wadsworth, the future business model of this industry might not be based on transactional music sales for much longer. In the space of a year, the proportion of income derived from other sources – live gigs, merchandising, advertising, digital licensing, broadcast – has grown from £121.6m (11.4% of total revenues in 2007) to £195m (18% of the total in 2008).

"The industry is moving from a transaction based business to a usage and licensing business," says Wadsworth. He cites the interactive computer games Guitar Hero and Rock Band as key sources of income. Advertising opportunities for the music industry have grown with the splintering of media, he says.

"The more media proliferates, the more opportunities there are because music is an incredibly versatile content and can be used in association with many other different media," he says. "It can be the featured content – such as when you buy an album – or it can be used in conjunction with visual content, if you are consuming a movie. Or it can be background. There are many levels music can be consumed at."

He is excited by the revenue being generated by music subscription sites such as Spotify and We7 and at the growing income in royalties collected by the industry body PPL from broadcasters, shops and bars.

Artists and labels are all the time thinking differently about how they bring their product to market. In particular he highlights tomorrow's release of Mariah Carey's new album Memoirs of an Imperfect Angel, which comes with a 34-page booklet produced by Elle magazine, including high-end lifestyle advertising from such clients as Elizabeth Arden and the Bahamas Board of Tourism.

"There's obviously a lot of money on the table from luxury brands," says Wadsworth. "They've realised that Mariah Carey's brand somehow lines up with that and the income they're deriving from it goes a long way to funding the launch of the album, which is a pretty innovative move."

The Radiohead model for selling its 2007 album In Rainbows, he notes, was not just about giving away a download for very little, it was also about marketing a deluxe CD edition. "There was the physical campaign, 25 or 30 quid for a special box set, which generated huge income for the band. They said here are two extreme ways for music to be consumed and all points in between are legitimate."

That release was reported by The Times under the headline "The day the music industry died". Wadsworth challenges this type of thinking, claiming there was an advantage to music being in the immediate line of fire when the digital revolution began. "This was the first content industry to be affected by unofficial file sharing but by being first we've had that much more time to adapt."

It was a decade ago, when Wadsworth had just taken over an EMI that was still buoyant from the Britpop era with a roster that included Radiohead, Blur and Supergrass, that he first realised the threat from downloading. "My internet guru said to me, 'On this disc is the whole Beatles catalogue and I've just downloaded all of it from the Internet'. I thought, 'Things are going to be different from now on'."

He worked for EMI for 26 years and during a decade in charge of the company, oversaw the global rise of British artists including Coldplay, Gorillaz and Amy Winehouse. He also faced criticism when Robbie Williams's 2006 album Rudebox failed to produce the returns expected of an artist with a contract worth £80m. When the company was bought by Guy Hands's private equity firm Terra Firma, acts such as Radiohead and Paul McCartney decided their futures lay elsewhere. Wadsworth followed them out of the door in January last year, with Music Week saying his departure caused "dismay and confusion" among EMI's artists.

The decision caused shock in the wider music industry, with Wadsworth already chairman of the BPI. He chose to remain in that role and has played his part in helping to shape the government's attempts to tackle illegal file-sharing. Discussing this, he is at pains to emphasise that record companies do not see file-sharers as villains. "The industry is wrongly often accused of wanting to criminalise its consumers and we don't," he says. "None of the solutions we are supporting involve criminalisation. All we want is an effective legislative framework, not a hammer to crack a walnut."

BPI research, he claims, suggest that many illegal downloaders respond to basic warning letters. Those that take unlicensed material on a grand scale face having their broadband width reduced by their Internet Service Providers but Wadsworth anxiously points out that in introducing such a penalty "you are not removing their internet". Softly, softly, it's the Wadsworth style.

This month Lily Allen who Wadsworth brought to EMI, took a rather more robust line on her MySpace blog, claiming that illegal file-sharing was making it "harder and harder for new acts to emerge", leaving the charts dominated by "nothing but puppets paid for by Simon Cowell". She wrote: "I think music piracy is having a dangerous effect on British music, but some really rich and successful artists like Nick Mason from Pink Floyd and Ed O'Brien from Radiohead don't seem to think so."

Such pessimism is not for Tony Wadsworth. "The development of technology has meant music is consumed in more places in more ways than ever before – that is a great thing," he says.

"We must make sure that consumption results in fair dues being returned to the people who invest in and create that music. I think we are getting there, I think we are succeeding in that struggle."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments