New Mars study suggests an ocean's worth of water may be hiding beneath the red dusty surface

A new study suggests Mars may be drenched beneath its surface, with enough water hiding in the cracks of underground rocks to form a global ocean

Mars may be drenched beneath its surface, with enough water hiding in the cracks of underground rocks to form a global ocean, new research suggests.

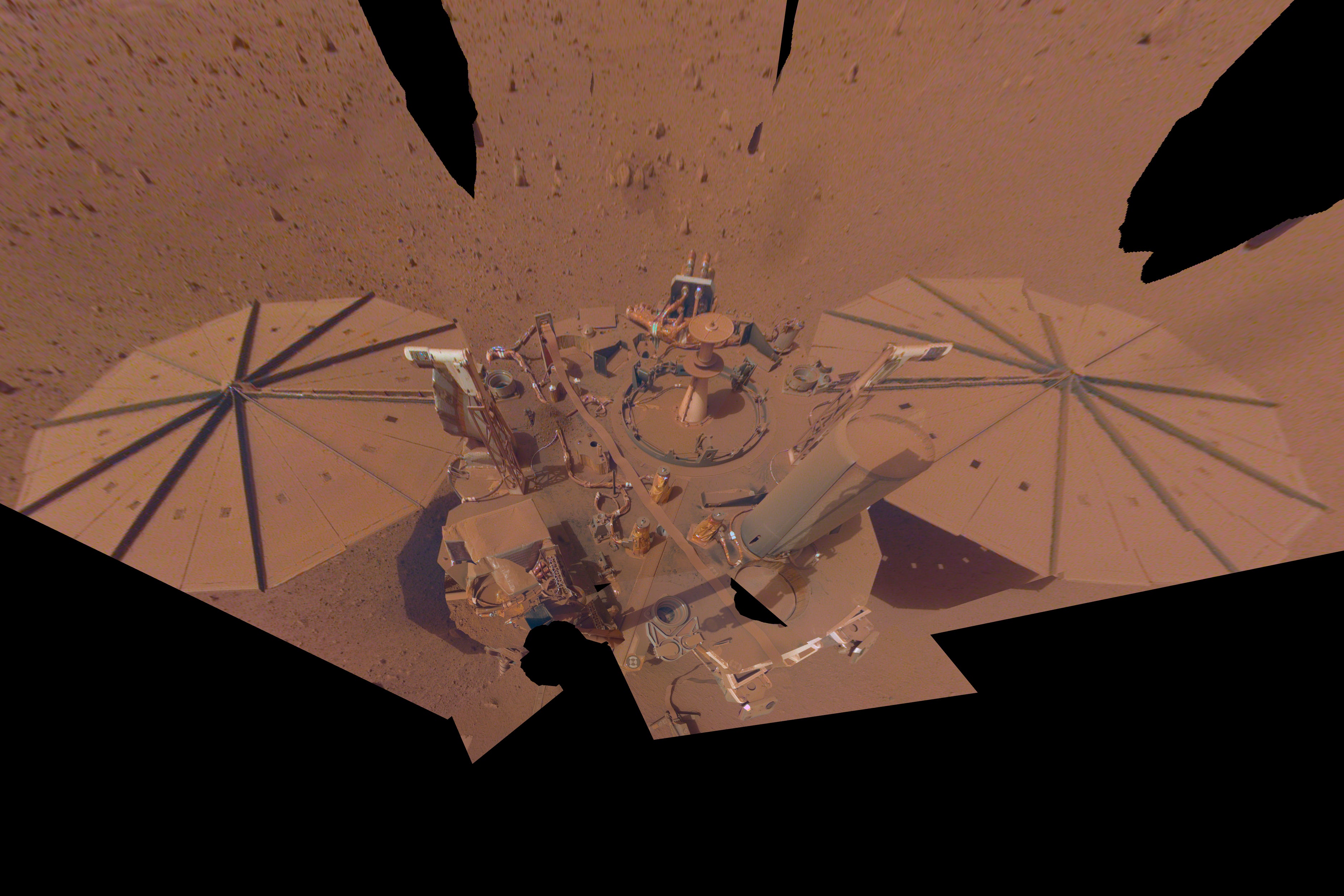

The findings released Monday are based on seismic measurements from NASA’s Mars InSight lander, which detected more than 1,300 marsquakes before shutting down two years ago.

This water — believed to be seven miles to 12 miles (11.5 kilometers to 20 kilometers) down in the Martian crust — most likely would have seeped from the surface billions of years ago when Mars harbored rivers, lakes and possibly oceans, according to the lead scientist, Vashan Wright of the University of California San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Just because water still may be sloshing around inside Mars does not mean it holds life, Wright said.

“Instead, our findings mean that there are environments that could possibly be habitable," he said in an email.

His team combined computer models with InSight readings including the quakes’ velocity in determining underground water was the most likely explanation. The results appeared Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

If InSight’s location at Elysium Planitia near Mars’ equator is representative of the rest of the red planet, the underground water would be enough to fill a global ocean a mile or so (1 kilometer to 2 kilometers) deep, Wright said.

It would take drills and other equipment to confirm the presence of water and seek out any potential signs of microbial life.

Although the InSight lander is no longer working, scientists continue to analyze the data collected from 2018 through 2022, in search of more information about Mars’ interior.

Wet almost all over more than 3 billion years ago, Mars is thought to have lost its surface water as its atmosphere thinned, turning the planet into the dry, dusty world known today. Scientists theorize much of this ancient water escaped out into space or remained buried below.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks