‘The backlash can’t break us’: Meet the couple fighting for love and equality in India

India’s government calls same-sex marriage ‘an urban elitist view’. For Ananya Kotia and Utkarsh Saxena, legal recognition would be the natural next step for a relationship that began in 2008, they tell Namita Singh

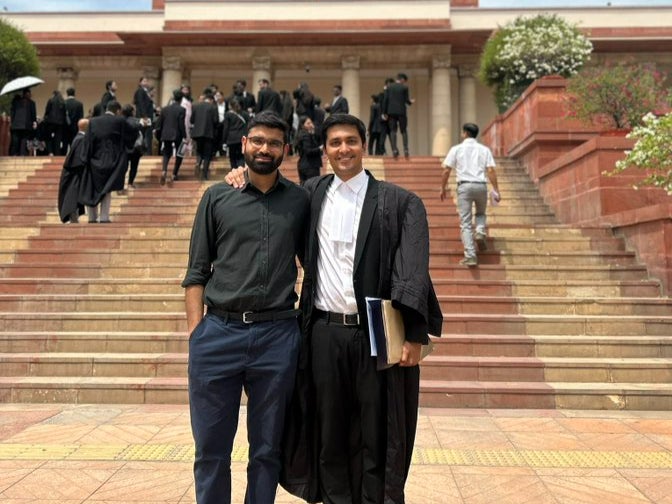

On the stairs of India’s Supreme Court, Utkarsh Saxena has one hand wrapped around the shoulder of his partner, Ananya Kotia. In turn, Ananya is holding his boyfriend around the waist, as any couple would. But there’s more to this picture than meets the eye.

Taken immediately after they presented their arguments for marriage equality, it was a moment Saxena never imagined he would see in this lifetime.

A five-judge constitutional bench has reserved its verdict on a batch of petitions seeking legal recognition of same-sex marriage in India. At the hearing in April lasting 10 days, at least 18 couples, including Saxena and Kotia, argued about the rights and privileges that come with marriage, along with their right to equality which is protected by the law. India’s government, on the other hand, opposes marriage equality, calling it an “urban elitist view”.

Despite government resistance, the petitioners “mostly felt a deep sense of gratitude”, says Saxena as he describes the picture.

“The highest court of the land patiently heard our tribulations, struggles, and prayers for equal rights in hearings that were live-streamed to the entire country, making it a dining table conversation in homes,” he tells The Independent.

“That itself is an incredible development and we were grateful and proud that the movement had reached that point.”

The struggle for recognition has come a long way since 2008 when they first met in college as two closeted gay men, at a time when homosexual relations were still criminalised in India.

“We hadn’t spoken to anyone about being gay,” says Kotia. “I was very scared about even confronting it myself, let alone talking to someone else about it.

“But when we met in college, we had a lot of geeky common interests. We were pretty nerdy about Indian politics, economics, current affairs and that kind of stuff,” he says.

They soon became good friends. Calling each other late at night on landline phones became a ritual where they would have passionate discussions about the news of the day, setting the stage for a college romance.

But their relationship remained a secret for the first six years, which was “suffocating in its own way”.

“Growing up was quite difficult in the 2000s, you know,” recalls Saxena. “There was no conversation around LGBT+ rights, especially in schools. There was a lot of stigma around it.

“There was a lot of mockery and ridicule in movies and popular culture and that was just debilitating,” he says.

Born into a military family, Saxena went to an all-boys school and later became a criminal lawyer. All three were hypermasculine settings in a country where LGBT+ people are often represented as feminine, caricaturish and the object of ridicule in mainstream Hindi cinema.

“I couldn’t relate with the queer people who were depicted on screen because especially in Bollywood, they were in fashion or just entertainment and I didn’t see professionals or students or kids my age being depicted on screen.

“And I think there was this big tussle of maybe being queer means that you are not, and to use the word loosely in a conventional sense, ‘masculine’.

“And I was good at sports. I was in my track team, I was in my sports team and that was very confusing. I was like, ‘no, no, no, how can you be [gay] because you, you are good at sports?’.

“I went through denials. I tried to pretend I liked girls so I could fit in. Those years were difficult and challenging,” he says.

The emotions resonate with Kotia as well. “I used to go in denial and completely bottle it up,” he says. “I would often feel that what’s the point of working hard and studying if, at the end of it, I can’t really have a wholesome life… which is that you have with some professional success but family is a very important part of it.

“You have kids, you have a wife and that’s how it is meant to be, based on observations on TV, books and people around you. And I think from a very young age, I think the hardest part was [to] deal with the fact that it is completely ruled out for me.”

Saxena also battled fear of abandonment, but meeting Kotia at the age of 20 helped “put his anxieties at bay a little bit”.

“We both felt like even if the world is against us, at least we have each other,” says Saxena, as he talks of meeting his partner of 15 years at New Delhi’s Hansraj College debating society during auditions where he was the president while Kotia was auditioning as a fresher.

Their staggered personal journey of coming out to each other and their family members played out alongside a shifting landscape of LGBT+ rights in the country.

Saxena came out to his sister in 2009, the same year India witnessed a landmark Delhi High Court ruling that found criminalisation of homosexual relations under section 377 to be in direct violation of fundamental rights provided by the Indian constitution.

Four years on, in 2013, the country’s top court overturned the judgment, bringing back the law that awarded a maximum of life imprisonment to a person who “voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal”.

While two years later Saxena came out to his mother, his partner was yet to inform his own family members.

Kotia recounts confiding in his sister for the first time in 2018, the same year when a five-judge constitutional bench of the Supreme Court decriminalised consensual same-sex relations. While he could not recall whether it was before or after the judgment, he reflects on how he accidentally disclosed his decades-long, carefully guarded secret.

“I think my sister and I were fighting on the phone about something silly and I just blurted it out. I just wanted to make the point that ‘it’s not only your life, which is difficult. I also have these challenges’.”

He also noticed the increasing number of nuanced portrayals of same-sex relationships in Indian cinema, which started providing glimpses of hope and acceptance during the couple’s formative years, as the movies and shows on TV evolved from mockery and stereotyping to a more sensitive and inclusive representation of LGBT+ characters.

“I used to tell my sister, ‘Oh, can you tell Mummy to watch Made in Heaven on Amazon Prime’,” he says referring to a 2019 nine-episode series dissecting weddings as a concept in modern India while carrying a dignified portrayal of the lead character who is queer. “I just wanted to make sure that she sees them and I was always curious about what her reaction would be just to gauge where she is in all of this.

“I mean, she used to cry. She was very invested in these stories. There was no sense of disgust or that, you know ‘what is this? I don’t understand this’.”

Seeing these small signals of acceptance from his mother gave Kotia confidence that he could come out to his parents someday. Now a PhD student at the London School of Economics, Kotia felt more confident and finally told them during the pandemic lockdown in 2020.

“When I spoke to my mother about this, she was so happy that we found this lifelong companionship. She was very honest when she told me that ‘if you had told me when you were 20 and 18, I don’t know how I would have reacted’ and she understood it a lot less at that time.”

This familial support was crucial to the couple’s decision to file a petition seeking marriage equality in December last year.

“Three factors that were just converging at the right time,” says Saxena, as he explains their decision to move ahead with the petition. “Legally, the jurisprudence has been evolving and advancing. Privacy became a fundamental right. And homosexuality was decriminalised. So this was the natural next step.”

The decision to file the petition was not taken lightly for it required not only their unwavering commitment but also the support and understanding of their families.

“Earlier, it was like a family thing. Everybody was very happy and they loved Kotia. But it wasn’t public,” says Saxena.

“My parents’ friends didn’t know, especially like my father’s armed forces circle didn’t know. The military friends didn’t know. So, last year when we decided to file the petition, it was like them coming out to their friends about their son, right?

“So that would... that triggered some conversation, some concerns about what it would mean for them.

“And also because they were concerned for me, for my safety and you know, social media can be cruel. There’s a lot of trolling.”

But Saxena and Kotia felt that they were in a secure place in life where they could withstand the pushback. “The backlash can’t break us. We’re not that fragile any more,” says Saxena.

The arguments in court were concluded in May, with the Supreme Court bench reserving its judgment until after it returns from summer vacation. By the completion of the submissions, the government of India indicated its willingness to extend some social benefits to same-sex couples, while maintaining its opposition to marriage equality.

The judges also said they do not want to leave same-sex couples “with nothing in their hands” if the court eventually decides against their petitions for the legal recognition of their union.

“I think we have two reasons for asking for marriage,” says Kotia. “The first is that a lot of rights come associated with marriage. So for instance, if Utkarsh has a job or I have a job, the other person can’t get on the group insurance for health.

“Similarly, if there’s a medical condition, I don’t have any legal status to be able to take decisions on his behalf, if he’s incapacitated.

“So there’s all, there’s a whole host of rights which are governed by legislation or sort of government. executive notifications which mention the word marriage.

“But there’s also a second reason, which is just an emotional reason,” says Kotia. “It’s simple in my head that if you love each other and you found lifelong companionship, the next step is marriage.

“So, what grounds can you then come up with, to deny that same right to homosexual people or to transgender and basically to anyone who’s not a heterosexual?”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks