Forget the Sixties, Woodstock has been rocking with artists and creativity since 1902

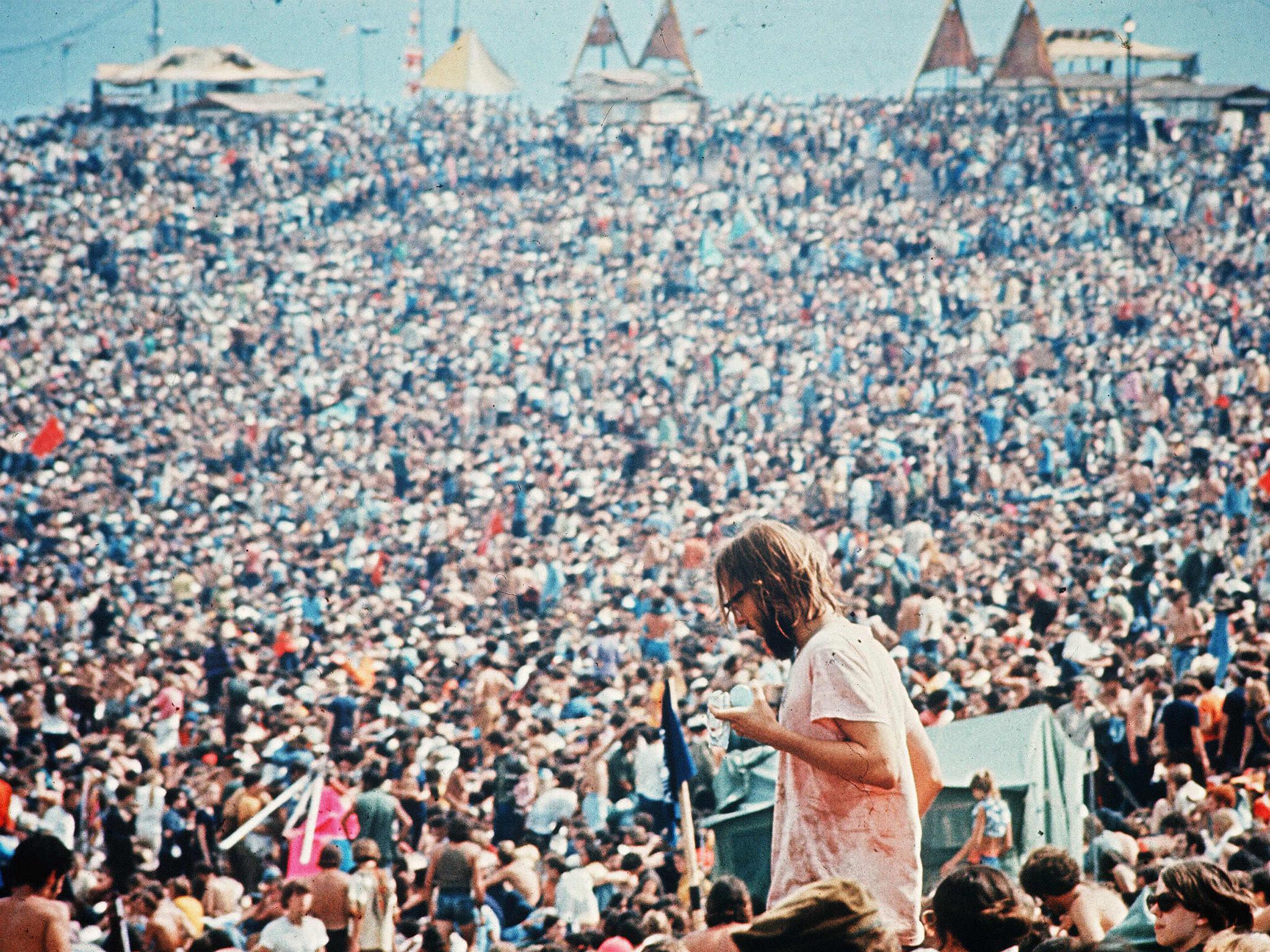

As thousands descend once again on Woodstock for its 50th anniversary festival, resident Sunshine Flint explains why it remains the most famous small town in America

If you stand on the village green of Woodstock, New York, with the white spire of the 200-year-old Dutch Reformed Church behind you, you will see a charming small town of low clapboard buildings, one with expensive coffee shops, an independent bookstore, and pricey boutiques, but no chain stores and not a single traffic light.

You’ll see couples wandering in and out of the art galleries, small kids licking icecream cones, and groups of millennials up for the weekend from New York City rolling in for brunch. And if you stand there long enough this summer, you’ll likely see some confused tourists rock up and ask for directions to “where the festival was held.” They won’t be the first to be told it’s about 50 miles that-a-way.

Growing up in Woodstock I had to deliver the same news more than once. This August is the 50th anniversary of the most famous music festival in the world, but like the original 1969 concert, the official celebrations won’t come within miles of the Catskill Mountains town it’s named after. Fans will congregate in Bethel Woods, near Max Yasgur’s farm, to see some of the big acts of the 1960s such as Santana and John Fogerty of Creedence Clearwater Revival (both played those muddy fields 50 years ago), as well as Ringo Starr and his All Starr Band, while the town will carry on in its own fashion, business as always. (The Woodstock 50 festival promoted by original Woodstock co-founder Michael Lang won’t be taking place.)

But while Woodstock the town and Woodstock the festival are forever entwined in the public consciousness, Woodstock’s appeal and bohemian reputation isn’t derived from the festival. In fact, it’s the reason why the concert was meant to be held there in the first place.

Founded by the Dutch, carved out of the Great Hardenbergh patent purchased from local Indian tribes, and then English settlers, the town was incorporated in 1787. By the late 19th century, Woodstock, a farming community punctuated with lumber mills and tanneries, began attracting visitors because of its bucolic location less than 100 miles north of New York City in the Catskill Mountains. (For a comprehensive history there’s the 700-page tome, Woodstock: History of an American Town, by longtime Woodstock historian Alf Evers.)

First coming up the Hudson River by steamboat and then by rail, New Yorkers of means flocked to the grand hotels built on mountain tops, most of which have long since burnt down. “Local people realised they could make money from what people saw in the land and the fresh mountain air,” says Richard Heppner, today’s town historian. “The original mountain houses were built for people coming up from the city to escape the heat and humidity in the summer and avoid diseases like tuberculosis.”

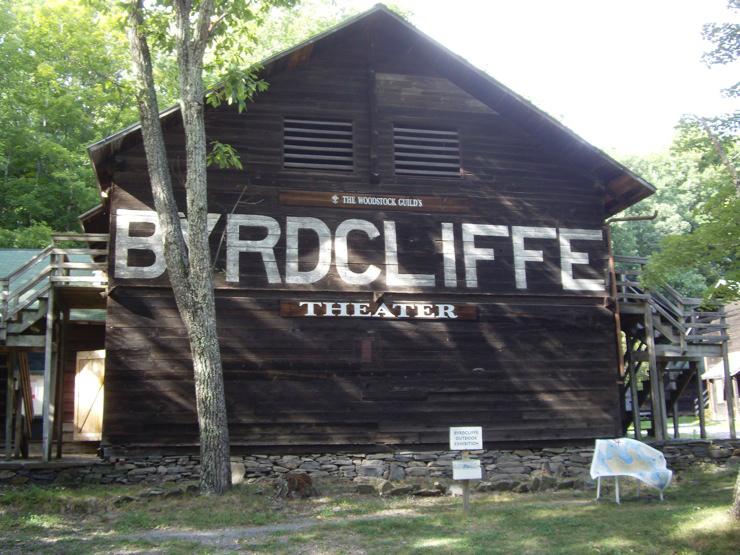

But it was the utopian vision of one Englishman, Ralph Radcliffe Whitehead and his American wife, Jane Byrd McCall, that laid the foundation for Woodstock’s avant garde reputation over a century ago. The wealthy heir of a Yorkshire textile mill family, Whitehead entered Balliol College, Oxford, where he absorbed the social reformist philosophy of John Ruskin and the aesthetics of William Morris. The couple eventually found themselves in America looking to found an artists’ colony. In 1902, they bought 1,500 acres on the mountain above Woodstock, attracted by the Catskills’ wealth of natural beauty and access to New York City. The Byrdcliffe Art Colony was born.

The creative community on the mountain slopes above town drew artists, craftsmen, sculptors and writers to live and work in the cabins and studios the Whiteheads had built. They created Arts & Crafts furniture and decor along with pottery, textiles, and jewellery to be sold in New York City. In Whitehead’s free-thinking organisation, women artists were able to avoid some of the confines of society, and it attracted visitors such as feminist and suffragette Charlotte Perkins Gilman, writer Owen Lister, and naturalist John Burroughs.

The concentration of artists and the beautiful scenery spurred the Art Students League of New York City to open a summer school, and the town soon filled with painters carrying easels on the high street and galleries that drew tourists. While Whitehead’s vision was never fully realised, Byrdcliffe is today a non-profit arts centre that provides exhibitions, performances, and residencies to various artists.

One of Whitehead’s early partners, Hervey White, broke away from Byrdcliffe to start the Maverick Arts Colony on the other side of town, attracting a like-minded set of artists and musicians. In 1916, White began the Maverick Concerts series, which is still running today in his hand-built concert hall, the oldest continuous chamber series in the country. The Maverick Festival was an open air, annual event held every year from 1916 to 1931, whose participants’ commitment to fun and freedom (and the local cider) were a precursor to the famous festival in 1969.

In the sixties, came rock musicians such as Bob Dylan and The Band, and the hippies and the weekenders soon followed. Today, Woodstock’s year-round population is 6,000 but swells to 12,000 when second-home owners are included. The mountains, the streams, and the nonconformist spirit also attracted musician David Bowie, writers such as Neil Gaiman and movie stars like Uma Thurman. The Catskills region is so spread out and Woodstock’s population so immune to celebrity that privacy is pretty much guaranteed. Living in the woods up a winding mountain road helps too.

The woods are indeed “lovely, dark and deep” … and quiet. For city dwellers the lack of all noise at night is startling and driving on pitch-black country roads takes some getting used to. Singer/songwriter Amanda Palmer bought a house in Woodstock in 2013 in what she calls “a little bit of an accident” with her husband, author Neil Gaiman.

She says at first she didn’t like Woodstock, she didn’t want to live in the middle of nowhere, knowing no one, but “the woods have made me submit. They tie me down at night and force me to see reason.” Gaiman and Palmer moved here more permanently a few years ago with their son, Ash. She composes at nearby studios and occasionally performs at local venues, while Gaiman has a writing cabin on their property. The town’s appeal is “the proximity to nature with proximity to the city,” Palmer says. “And the art colony set the stage. You only need a little bit of art in the water to freak a place out forever — artists can smell other artists.”

It was this special reputation as a certain kind of cultural-rural paradise that drew my family here in the late 1970s from Brooklyn, along with a host of others looking for alternative lifestyles and health food stores, from former hippies to Buddhist monks. As a child, I roamed the woods, eating handfuls of wild blackberries and following mountain streams up bosky slopes. Growing up in a town like Woodstock, my name didn’t single me out at school; although it did make me stand out, as I discovered in the course of researching this essay, when I found myself referred to in this 1987 New York Times article about Woodstock. That was weird.

Its appeal is the proximity to nature and the city ... And the art colony set the stage. You only need a little bit of art in the water to freak a place out forever — artists can smell other artists

I also spent an inordinate amount of time in that haven for bookish children everywhere, the town library. In the 1920s, as the artists settled into the town permanently, they became involved in the town and created civic institutions. Members of the Woodstock Artists Association donated art books and raffled off artworks to raise money to launch what is now one of Woodstock’s most beloved and argued over institutions, the Woodstock Public Library. A few years ago, the library revealed another Oxfordshire, this time to the town of Woodstock, England.

After bushes were cleared away from the front of the library, a golden stone was revealed, the limestone standing out from the local bluestone slate like the sun peeping through grey clouds. The inscription reads:

1787—1937

To Woodstock, New York

In Kindred Sympathy and peaceful association

This Stone from Blenheim Palace

Is dedicated

By

Woodstock, England

In the year of the Coronation of

HM King George VI

Fortunately there is an exhaustive and strangely compelling history of the library, The Story of a Small Town Library, which reveals that in the spring of 1937, the wife of sculptor Bruno Zimm (he was president of the library at the time) wrote to the mayor of Woodstock, in England, informing him of Woodstock’s upcoming sesquicentennial. The swift response came that the town would send a stone for Woodstock, New York’s war memorial. A check of the Archives at Blenheim Palace turned up no information, but the Oxfordshire History Centre found minutes from a quarterly meeting of the Borough Council stating that “His Grace the Duke of Marlborough has kindly given a stone from Blenheim Palace to be built into the War Memorial at Woodstock USA.”

Is now a good time to let the good people of Woodstock, England, and the 12th Duke know that this mysterious war memorial was not built and eventually the stone was placed in an unused fireplace in the library for a decade because no one could figure out what to do with it? However, in 1948, it was used as a cornerstone for a new library extension and then moved to its present position when another wing was added 20 years later.

Today, Woodstock is going through its next metamorphosis. Just as Woodstock once absorbed the artists and then the hippies, now the town is adapting to a permanent influx of temporary visitors brought by Airbnb. The town’s zoning laws have long kept out hotel development, which meant that visitors either rented a house for the summer or booked a room at of the few B & Bs or motels near town. But today renting a small cabin or five-bedroom house with a pool is as easy as scrolling (if you search for Woodstock, NY over 300 rentals come up).

In 2018, Airbnb hosts in the Hudson Valley and Catskills earned more than $50 million and the company forecasted the Catskills as number 11 on their list of 19 top destinations in 2019. The town is grappling with its own success, which has resulted in an uproar over the lack of rentals for long-term residents, and noise, trash, and parking complaints, leading the Woodstock town board to require owners to register with the county and limit the number of days a house can be rented out.

The rise of Airbnb also comes with the same technology that allows someone to post a selfie at the Big Deep swimming hole or hike up Overlook Mountain on Instagram and the GPS so their friends can find it. It also (or perhaps because of it?) coincided with the rise of the maker culture, field-to-fork dining, and handcrafted experiences that Ralph Whitehead surely would have appreciated.

You can’t find this as easily in the Hamptons as you can in the Catskills. These visitors want to sit around the firepit outside their cabin in the woods, not around a table at a nightclub, but they still want to go out for brunch the next morning. I had always thought Woodstock was impervious to change: the stores would sell tie dyes and Birkenstocks forever, and ageing hippies and tourists would always dine at the same three restaurants. But a new crop of shops and restaurants have opened to accommodate the demand for craft cocktails and eggs Benedict and designer fireplace accessories, with city prices to match. And while the Woodstocker in me is appalled at paying $12 for a drink, the Brooklynite thinks “Hurrah, lavender syrup!”

But Woodstock’s unpolished, live-and-let-live appeal continues. True, there are more deer ticks and black bears than when I was a kid, but the frogs peeping down by the pond, the fireflies winking in and out at dusk, the green folds of the ancient mountains, the inky black sky full of stardust, remain as magical as ever. And there’s something more, something ineffable that keeps people coming here.

Jazz great Sonny Rollins, who moved to Woodstock over a decade ago, says he felt that special quality when he visited for the first time. “When we came here, there was an aura in the town. It seemed to have a gentleness almost,” he says. “Artists and musicians and painters and writers – we don’t always feel comfortable in this world. Woodstock just had that feeling about it.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments