Whaling may have all-but ended, but threats to the world’s whales remain

For decades the fight was against whaling, but these majestic animals are now more under threat from pollution and sonar. Some species classed as ‘endangered’ are probably already extinct. Ashley Coates on the ocean’s new battle lines

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.After more than a decade harassing Japanese whaling vessels in the Southern Ocean, marine conservation organisation Sea Shepherd announced this summer that it would no longer be obstructing the seasonal hunt for minke whale. The group said the cost of sending their vessels south to the waters around the Antarctic had grown in recent years and their activities have been further disrupted due to the alleged use of military tracking technology targeting their ships and new anti-terrorism laws passed by Japan.

In March this year, 333 minke whales were caught by Japanese whaling companies. Japan's government insists the hunting of minke whale is for research purposes, a claim that is widely contested by conservation groups.

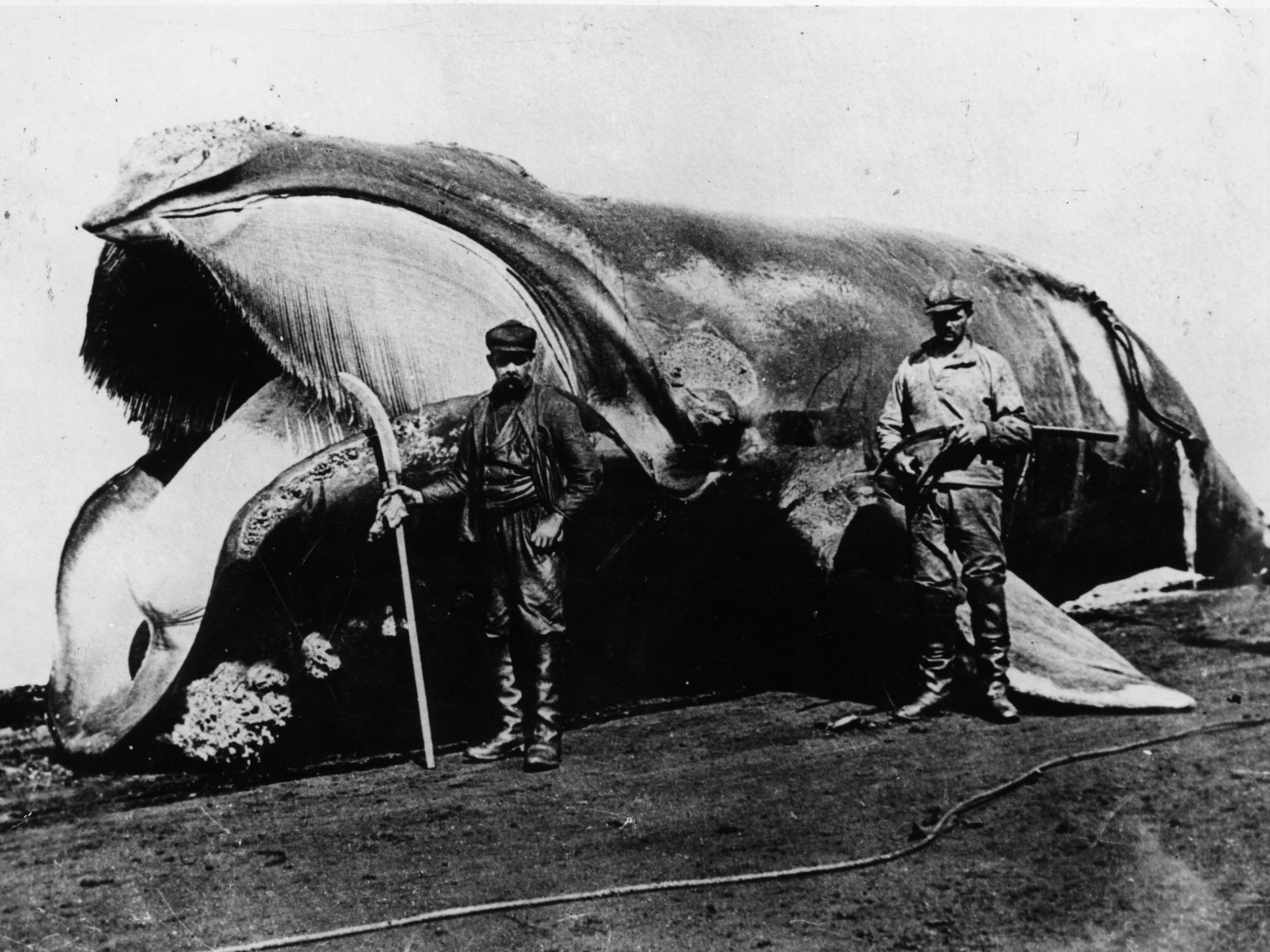

Having started out as small hunting expeditions using spears and primitive harpoons launched from rowing boats, whaling rapidly expanded into an industrialised business in the 19th and 20th centuries. The advent of steam power and projectile or exploding harpoons meant that by the 1930s, 50,000 whales were being killed every year.

As whale numbers diminished, concerns that whole species may become extinct eventually led to most whaling being banned by the International Whaling Commission in 1986. Although some populations have been able to bounce back, many species remain depleted and some are still in decline.

A study released this month suggests that endangered Antarctic blue, Southern right and fin whales are unlikely to reach even half of their 19th century numbers by 2100.

“What our study has shown from historical whaling is that there were many species that were vulnerable to significant impact from hunting,” said the report’s author Viv Tulloch, of the University of Queensland. “Even a couple of hundred individuals hunted a year over a number of years has been shown to significantly affect populations and significantly impact their numbers.”

“Right” whales were given their name as whalers found they were able to extract large amounts of oil and baleen from the processed animals - making them the “right” whale to hunt. They’re also significantly slower than their close relatives, the blue and fin whales, so they were easier to catch and unlike many other species, right whales float when dead. Consequently, 45,000 right whales were killed between 1805 and 1844, bringing them very close to extinction.

The last survey of Southern rights suggested there are now around 7,500 of these whales living in the waters surrounding the Antarctic and Australia, representing a modest increase on the numbers they were reduced to before the whaling moratorium. The Northern Atlantic population of right whales have fared worse than their southern cousins and are on the IUCN Red List as an endangered species. Despite the hunting of this species officially ending in 1937, scientists now believe anthropogenic factors such as boat collisions and entanglement in fishing gear are the main causes of death for up to half of right whales in this region every year.

Their low numbers and slow breeding patterns make recovery extremely difficult and today the population of North Atlantic right whales has been reduced to just 300-350 individuals. But the whaling that does continue today is not regarded a major threat to the stability of the world's whale populations.

Largely as a consequence of hunting and the industrialisation of the river that gives this dolphin its name, Yangtze river dolphin (or baiji) are technically classified as critically endangered but are now most likely to be extinct. According to the most recent estimates, Hector's dolphins are down to around 2,000 individuals, with entanglement in fishing gear largely to blame. A subspecies of the Hector’s dolphin, known as Maui’s dolphin, are thought to number as little as 43 individuals.

Danny Groves, communications manager at the UK-based Whale and Dolphin Conservation (WDC) charity says human activity such as fishing is largely to blame for the low numbers of Maui.

“Maui's dolphins are only found around the shallow coastal waters of New Zealand's North Island, where their predominant threat is bycatch or entanglement in set gill-nets, a static fishing gear used widely within habitat critical to this tiny population of dolphins,” he says.

“Maui's dolphins have never been as abundant as their cousins the Hector's dolphin, from the South Island," Groves continues, “but their numbers are declining rapidly and experts predict that unless further measures are taken to protect them, the Maui's dolphin will be extinct within the next 15 years – if not sooner.

“With only 43-47 individuals left, and only 10 of these mature females able to reproduce and add to the gene pool, the clock is ticking very loudly.”

Elsewhere, the latest estimates suggest there are only 1,100 South Asian river dolphin left, and 1,000 Narrow-ridged porpoise. The world’s smallest porpoise, the vaquita live exclusively in the Gulf of California off the coast of Mexico, and are one of the most endangered marine mammals on the planet. Despite a series of emergency measures from the Mexican government aimed at protecting these animals, conservationists remain concerned about their long-term future.

“The population has declined by more than 75 per cent in the past three years and currently fewer than 50 vaquita remain,” says Groves. “The single biggest threat to this species is accidental catch in illegal fisheries targeting yet another endangered species, a fish known as totoaba.”

Of the larger whales, there are between 10,000 and 25,000 of the world's largest animal, the blue whale, still in existence, far less than the roughly 350,000 animals thought to be roaming the seas before the hunting era began.

Today the most significant human threats to these animals are not Japanese whaling fleets, which mostly hunt smaller minke whale, but other factors such as manmade sonar, collisions with boats, entanglements in fishing gear, habitat destruction and industrial pollutants such as PCBs.

The link between naval sonar and strandings was established in 1996 when a group of 12 Cuvier’s beaked whales and one one Gervais' beaked whale beached shortly after a Nato “Shallow Water Acoustic Classification exercise” in the Gulf of Kyparissia, near Greece.

Sonar emitted from military vessels can be as loud as 235 decibels, 100 decibels higher than you might expect at the loudest rock concert.

In a world where sound is often more important than sight, whales and dolphins use a natural form of sonar (or echolocation) to hunt for prey and communicate with each other. As such, they not only have a heightened sense of hearing, but specially adapted parts of the brain that allow them to process information about their environment and communicate with other whales over hundreds of miles.

Low-Frequency naval sonar emitting in the range of 100 to 500 hz can travel for many miles and cause whales considerable distress and hearing damage. In some cases, it is thought that the sonar can spook whales that have gone on a particularly deep dive, meaning they return to the surface faster than they should, leading to nitrogen narcosis – commonly known to scuba divers as the bends.

Conservationists say there are ways of mitigating the negative effects of naval sonar, without banning its use entirely. “We recommend not carrying out large exercises in areas where populations of whales and dolphins can be found, like the west coast of Scotland,” says Groves. “Using lower frequencies, creating exclusion zones, not using sonar if pods are spotted, not exploding ordnance in these sensitive areas and restricting these activities at certain times of the year would all help."

While it is possible for the effects of naval sonar to be limited by the world’s navies, the historic use of polychlorinated biphenyl (PCBs) in a range of industrial applications has led to a release of persistent toxic pollutants that are almost impossible to remove from the oceans.

Groves says: “PCBs are a threat to the immune systems of whales and dolphins and also affect the ability of whales and dolphins to reproduce, placing populations under threat. Female whales, dolphins and porpoises sometimes pass on a large and potentially fatal proportion of their PCB burden to their first-born calves, both via the womb and through their milk.”

Apex predators such as the killer whale are particularly vulnerable as the concentration of these compounds becomes more intense further up the food chain. An autopsy of one of the UK’s last native killer whales, a female known as Lulu, found that she contained “shockingly high levels” of PCBs, roughly 20 times higher than scientists expect a cetacean to be able to cope with.

“The problem for whales and dolphins, and for us, is PCBs entering the food chain,” says Groves. “Plankton absorb PCBs from their environment and pass these onto the small fish and squid, which in turn pass on the PCBs in their body tissues to the large fish and squid that eat them. Finally, the PCBs from all the large fish (and the small fish and the plankton) are absorbed by the whales, dolphins and porpoises that eat them.

“The end result of this food chain is that whales, dolphins and porpoises accumulate large amounts of PCBs from their food. In fact, the levels of PCBs that accumulate in the bodies of some whales, dolphins and porpoises are so high that under laws in some countries, they could meet the criteria for being defined as toxic waste.”

Unfortunately for Lulu and the last remaining pod of resident killer whales of the coast of Scotland, PCBs are likely to be a major reason why the group has been unable to successfully produce a single calf in around 20 years. This pod will almost certainly become extinct when the remaining eight individuals die out.

The disposal of PCBs presents a major challenge for the industrialised countries that still have the contaminated products in use or PCBs seeping through the soil at landfill sites. They’re an extremely resilient compound that need to be heated to very high temperatures in order to be eradicated completely.

In the US, certain states have operated mass extraction exercises, taking huge amounts of material out of river beds known to have high PCB content. These exercises can be extremely expensive so most campaigning organisations are now focused on ensuring that the PCBs that are yet to enter landfill or sediment are disposed of safely.

WDC has argued for a Declaration of Cetacean Rights that would guarantee life, liberty and wellbeing for all whales. Philippa Brakes, who leads on ethics at WDC says: “Nation states would need to pledge to both recognise and then protect these rights. Ideally, this would be achieved by implementing legislation that prevented cetacean captivity, prohibited cetacean hunting and had a zero-tolerance approach to bycatch, with significant penalties.”

Protections would be afforded to both their natural habitat and their cultures, meaning human disruption to whale behaviour would also be banned.

In the 1980s, the imminent extinction of some of the largest and most spectacular baleen whales led to a global movement that eventually resulted in whaling being banned altogether.

More recently, conservation organisations in the US used the Marine Mammal Protection Act in a successful court action arguing against the use of naval sonar by the US navy. The proliferation of marine protected areas around the world, where fishing practices are restricted, also shows promise.

Today’s conservationists are hopeful that legislative and legal efforts, rather than near-extinction events, will result in safer seas for marine mammals.

Follow @Ashley_Coates

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments