Is war reporting losing the propaganda battle?

Politics, finance and technology have changed the role of on-the-ground reporters. A foreign correspondent for more than 40 years, Patrick Cockburn says the march of fake news should remind us of the vital need for eyewitness accounts

War reporting is easy to do but difficult to do well. No one taking part in an armed conflict has an incentive to tell the whole truth. This is the case in all forms of journalism, but in time of military conflict the propaganda effort is at its peak and is aided by the chaos of war, which hobbles anybody searching for the truth about what is really happening.

Military commanders are often more aware than reporters of the complexity and uncertainty of news from the battlefront. Citing such reasons, the Duke of Wellington doubted if a truly accurate account of the Battle of Waterloo could ever be written.

During the American Civil War, the Confederate general “Stonewall” Jackson made a somewhat different point. Surveying the scene of recent fighting with an aide, he turned to him and asked: “Did you ever think, Sir, what an opportunity a battlefield affords liars?”

He meant that war opens wide the door to deliberate mendacity because it is so easy to make false claims and so difficult to refute them. But there is more at work here than “the fog of war” that over-used phrase which exaggerates the accidental nature of the confusion and is often conveniently blamed as the cause of misinformation.

Propaganda, the deliberate manipulation of information, has always been a central component of warfare and never more so than at present. It tends to get a bad press and is the subject of much finger-wagging, but it stands to reason that people trying to kill each other will not hesitate to lie about each other.

The fashion popularised by President Trump for denouncing news contrary to one’s own interests as “fake news” has heightened the perception that information, true or false, is always a weapon in somebody’s hands. This is correct, but it does not mean that objective truth does not exist and that it cannot be revealed by good journalism.

The glib saying that “truth is the first casualty of war” is a dangerous escape hatch for poor reporting or credulous acceptance of a self-serving version of reality spoon-fed by the powers-that-be to the media. On the contrary, there is nothing inevitable about the suppression of truth about war or anything else – though it is much in the interests of governments to demoralise critics by pretending their efforts are puny and ineffectual. Journalists, individually and collectively, will always be engaged in a struggle with the propagandists that will sway backwards and forwards; but victory for either side is never inevitable.

While this general principle is true, I nonetheless have had the depressing sense since the First Gulf war in 1991 that it is increasingly the propagandists who are winning the content and that accurate eyewitness reporting is on the retreat. The causes of this are diverse: politics, finance and technology have combined to squeeze, or even eliminate, those whose job it is to find out what is truly going on and pass on news of it to the public.

These ill-winds may blow from many directions but their collective impact is to blight many types of on-the-ground news gathering: casualties include the provincial press in the US and Europe as well as my own field of foreign reporting, a speciality which, in the last two decades has been increasingly dominated by war reporting.

What has changed in war reporting in recent decades is the much greater sophistication and resources that governments deploy in shaping the news

Since 1999 I have been writing about conflicts in Chechnya, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Syria which are sometimes referred to as the post 9/11 wars, although in certain important respects predate the destruction of the Twin Towers. Reporting from war zones was always difficult and dangerous to do, but has become more so in this period. Coverage of the Afghan and Iraqi wars was often inadequate, but not as bad as the reporting in Libya and Syria. Misconceptions have arisen not just about matters of detail but about more fundamental questions, such as who is really fighting whom; and who are the winners and losers.

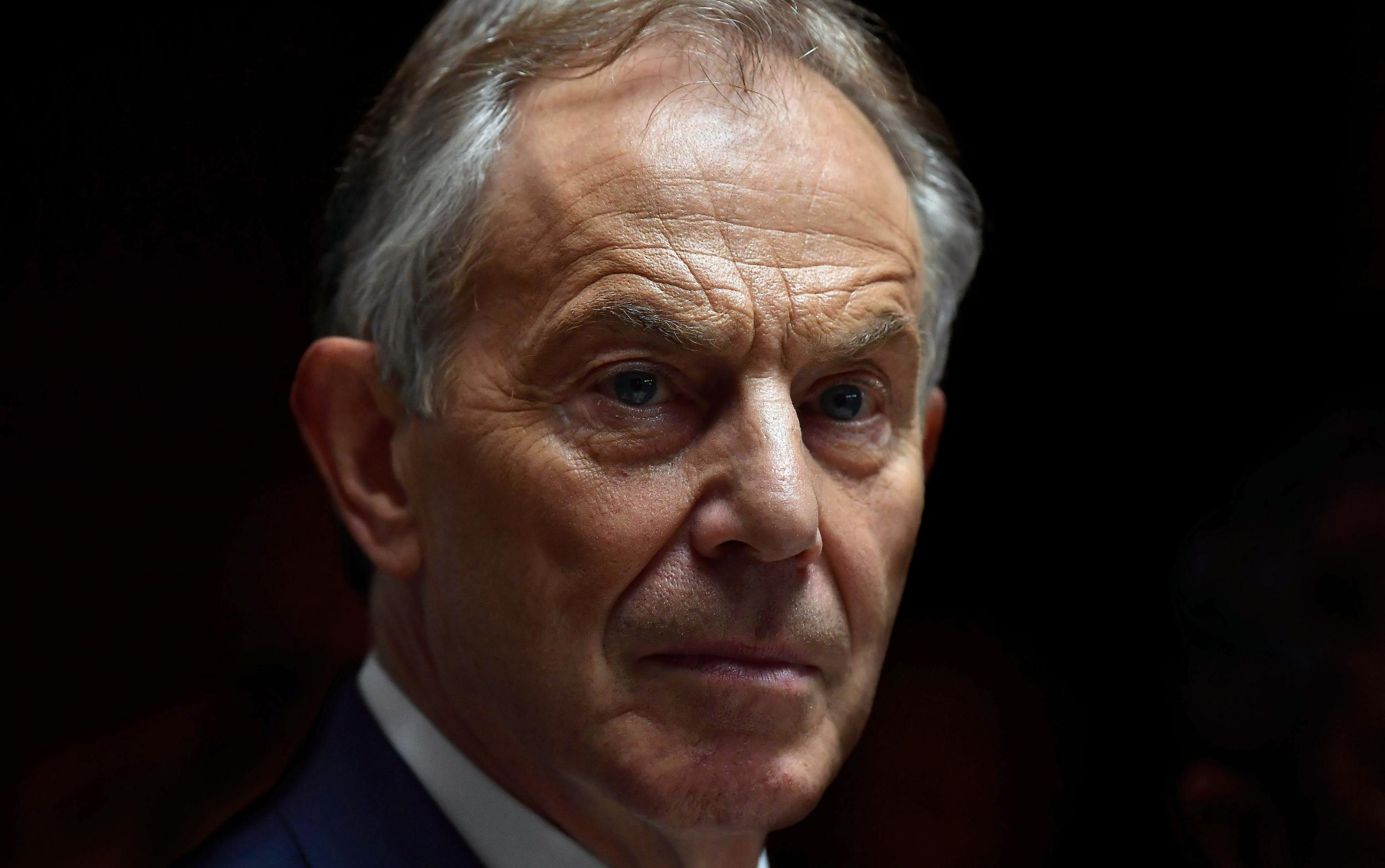

This ignorance is often portrayed as something afflicting the general public, while the powers-that-be, the controllers of “the deep state”, who may have their burrows in the Pentagon, Whitehall or the Kremlin, really do know what is going on. In fact, sad experience shows that this is not true and politicians, like Tony Blair and George W Bush in Iraq in 2003, take momentous decisions on the basis of limited and misleading knowledge.

The same was true of David Cameron, Nicolas Sarkozy and Hillary Clinton when they came together in 2011 to sanction the overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi by Nato in Libya. It should have been obvious from the beginning that the rag-tag opposition militias on the ground were in no position to replace him and that anarchy would be the inevitable outcome of the war.

As for Syria, political leaders and media organisations convinced themselves that the fall of President Bashar al-Assad was inevitable, while anybody with real experience on the ground could predict with a fair degree of certainty that this was not going to happen.

One should not be too dewy-eyed about standards of reporting 50 years ago, when most news organisations covering the Vietnam war dutifully toed the official line about the impending victory of the US and its allies. The media often exaggerates its own ability to find out truth and speak that truth to power.

Still, in Vietnam journalists were thick enough on the ground and were free to operate. They had in their ranks a fair number of perceptive dissenters who contradicted official optimism and said that the US was heading for disaster.

Sadly, the balance of forces has changed since Vietnam away from independent-minded journalism and towards those who act as messenger boys and girls for government views.

The change for the worse is detectable, although I do not want to sound too much of a Cassandra since the world turns slowly and usually there are fewer things changing than stay the same. There is nothing new about propaganda, controlling the news or spreading “false facts”. Ancient Egyptian Pharaohs inscribed self-glorifying and mendacious accounts of their battles on monuments in which their defeats are lauded as heroic victories.

What is new about war reporting in recent decades is the much greater sophistication and resources that governments deploy in shaping the news. Where governments do not have their own heavily-manned press offices, they hire private PR companies.

After Vietnam, the US military convinced itself – wrongly to my mind – that it had lost the war because of hostile media coverage. They were determined not to let this happen again and one could sense this approach at work in the Gulf war of 1991, a conflict that set a pattern for war reporting in the coming years.

Life was not difficult for propagandists in that early period: Saddam Hussein was easy to demonise because he was genuinely demonic. On the other hand, the most influential news story of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and the US-led counter-invasion was a fake.

This was a report that in August 1990 invading Iraqi soldiers had tipped babies out of incubators in a Kuwait hospital and left them to die on the floor.

A Kuwaiti girl working as a volunteer in the hospital told the US Congress that she had witnessed this horrific atrocity. Her story was confirmed by Amnesty International and was hugely influential in mobilising international support for the war effort of the US and its allies.

In reality the Kuwait babies story was a fiction. The girl who claimed to be a witness turned out to be the daughter of the Kuwaiti ambassador in Washington. Several journalists and human rights specialists expressed scepticism at the time because purported eyewitness accounts were full of holes, but their voices were drowned out by the outrage provoked by the tale. It was the classic example of a successful propaganda coup: the story could not be easily disproved and when it was – long after the war – it was only after it had had an immense political impact in creating support for the US-led coalition.

Twenty years later in Libya fabricated atrocity stories played, if anything, a more central role in persuading people that Gaddafi was a monster who had to be overthrown. The media uncritically ran with the story of a woman in Benghazi who claimed to have carried out a survey of Libyan women in opposition areas recaptured by Gaddafi’s forces and found that a high proportion said they had been raped by Libyan troops on official instructions.

In reality the Kuwait babies story was a fiction. The girl who claimed to be a witness turned out to be the daughter of the Kuwaiti ambassador in Washington

It was weeks before Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and UN committee published well-researched reports saying they had found no evidence that a survey had taken place and that the woman who said she had conducted it had been unable to put them in touch with a single rape victim. But by then the news agenda had moved on; I believe I was one of the few journalists to highlight the reports discrediting the original atrocity story.

Governments have openly or covertly expanded their efforts to control the news during the very period when the ability of journalists and news organisation to check what they are saying and doing has dropped precipitously.

I should add hurriedly that the reverse is true of The Independent which has added considerably to its foreign staff, including three additional correspondents covering the Middle East in recent times. Nevertheless, the decline has been steep in most of the media because it is the outcome of more than one development.

In the first place, reporting conflicts of any kind has become more dangerous compared to when I first started writing about the Troubles in Northern Ireland in the early 1970s. I used to joke that there was no group of gunmen without a press officer ready to promote their views and explain how their violence was purely retaliatory. Moving to Beirut during the civil war a few years later, I found militia leaders equally happy to give interviews and provide letters of accreditation allowing one to pass safely through their checkpoints.

Compare this to Syria today, where it is almost impossible for foreign journalists to enter territory held by the armed opposition because of the risk of being killed or kidnapped.

Reporting can be outsourced to local “citizen journalists” but they can only operate under licence from al-Qaeda type groups that do not tolerate dissent of any kind. Those individuals who attempt to give an even-handed version of the news pay a heavy price.

In the wake of the sarin gas attack on the opposition stronghold of Douma in Damascus in 2013, I came across a case illustrating just how high this price could be. I appeared on the same US television programme as Razan Zaitouneh, a heroic human rights lawyer with a history of criticising the Syrian government stretching back long before the so-called Arab Spring, who was speaking on Skype from inside Douma.

She spoke eloquently about the Syrian government’s responsibility for the gassing of hundreds of people. “I have never seen so much death in my whole life,” she said, and went on to describe doctors crying because they could not save the dying children.

But Zaitouneh did not confine her denunciations to atrocities carried out by the government side. Through her Violations Documentations Centre, she also criticised the actions of the jihadi Army Of Islam that was in control of Douma. A few weeks after I had spoken with her, gunmen burst into her office there and kidnapped her and three others. They have not been seen since and are believed to be dead.

There is an important point to be made here about what distinguishes objective news reporting from propaganda.

People unfamiliar with the way news is gathered often imagine that propaganda is all about invented tales such as the Kuwaiti babies or Muammar Gaddafi’s non-existent mass rape campaign – and, of course, propaganda often consists of credible lies designed to have maximum political impact.

But these are atypical events: it is much more common for propaganda to consist of true but carefully selected facts that show one’s own side in a positive light and one’s opponents as the face of evil. Since every side commits atrocities in war – and the wars in Iraq and Syria have been of peculiar brutality – it is possible to publicise these horrors with complete accuracy, but still give a distorted and propagandist view of what is happening.

In East Aleppo and Eastern Ghouta, for instance, the world was moved by pictures and videos of injured and dying children in hospitals following bombing and shelling by the Syrian government. There is no need to imagine that any of this was concocted, but it was noticeable in both places that one seldom saw pictures of armed Syrian and foreign Salafi-jihadis.

The BBC and CNN and others would try to verify the authenticity of atrocity videos from areas that their reporters could not enter except at the risk of their lives. But this rather missed the point: all these videos might be true but that truth would be selective. When it came to non-partisan investigation of atrocities, the human rights organisations had a rather better record – and a great deal more time and resources – than the journalists.

There are far fewer professional journalists in the field: publications have disappeared and foreign bureaux are closed or manned by a skeleton staff

A further weakness in the reporting of these post 9/11 wars is not really the fault of the participants. In all of them, political developments have been just as important as military action, but this is obscured by what I call “twixt-shot-and-shell reporting”. News organisations and the public are both attracted by the melodrama of war, but it can be very misleading.

I reported the war in Afghanistan in 2001-02 at a time when the international media was giving the impression that the Taliban had been decisively defeated. Television showed pictures of bombs and missiles exploding on the Taliban front lines and the Northern Alliance opposition forces advancing unopposed into Kabul.

But I followed the Taliban retreating south to Kandahar and it became clear they had not been defeated; rather their units were under orders to break up and go home. They knew they were over-matched and it would be better to wait until conditions changed in their favour, something that had happened by 2006, when they went back to war and continued to fight until the present day. By 2009 it was already dangerous to drive beyond the most southerly police station in Kabul because of the risk of Taliban checkpoints.

These obstacles to accurate reporting wars are great but they are surmountable. Many of them are not new: consider how the First World War was misreported. But for the media to push back effectively requires experienced, well-resourced journalists on the ground capable of investigating all aspects of a conflict.

But this is exactly what is not happening and the trend is in the opposite direction. Overall, there are far fewer professional journalists in the field: some publications have disappeared and foreign bureaux have in many cases been closed or are manned by a skeleton staff.

As war reporting becomes more dangerous, it gets more expensive and the money to pay for it is no longer always there. “In more than 40 years of reporting,” writes Sammy Ketz, the recently-retired Agence France Presse bureau chief in Baghdad and one of the most experienced journalists in the Middle East, “I have seen the number of journalists on the ground steadily diminish while the dangers relentlessly increase. We have become targets and our reporting costs more.”

Bullet proof jackets and drivers who rightly demand danger money need to be paid for. But, as advertising migrates from news organisations to internet platforms, the flow of essential but expensive information from the battlefronts of the Middle East has gone down.

Many of those who used to report from the region are out of jobs and whole areas of the world have largely fallen off the media map. When news organisations do pay for eyewitness reporting, they do not necessarily profit from it because the benefits are hijacked by the internet giants, which themselves employ no journalists.

Indeed, the decline of foreign reporting will continue until the internet platforms share a part of their vast revenues with those organisations that gather the news. Ketz describes the present situation as being as if “a stranger came along and shamelessly snatched the fruit of your labour. It is morally and democratically unjustified.” Freedom of expression is not much use unless there are the news outlets with the means and the reach to transmit essential information to the world at large.

The absence of on-the-ground eyewitnesses fosters ignorance and this, in turn, opens the door to more conflicts. Wars are usually started by those who think they can easily win them; and they often believe so because they have swallowed too much of their own propaganda. In almost all the wars I have written about since 9/11 – Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria and Yemen – those who decided to fight had no idea of the trouble they were getting into.

In 1991, my late friend Christopher Hitchens demolished Charlton Heston, who was a strong supporter of the bombing of Iraq, in a television encounter. Hitchens asked Heston to name the countries which shared a common border with Iraq. “Kuwait, Bahrain, Turkey, Russia, Iran,” replied the famous actor.

“If you are going to bomb a country you might at least pay it the compliment of finding out where it is,” replied Hitchens, as he delivered the knockout blow.

The exchange elicited much mockery of Heston at the time, but the decline of foreign reporting means there are likely to be more and more people who will share Heston’s enthusiasm for bombing places that they could not find on the map.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments