More than a century on, ghosts of one of Britain's worst mining disasters still haunt the Welsh valleys

When fire broke out at the Great Western colliery on 11 April 1893 – 125 years ago today – more than 120 men were trapped below ground. Godfrey Holmes picks up the extraordinary tale

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

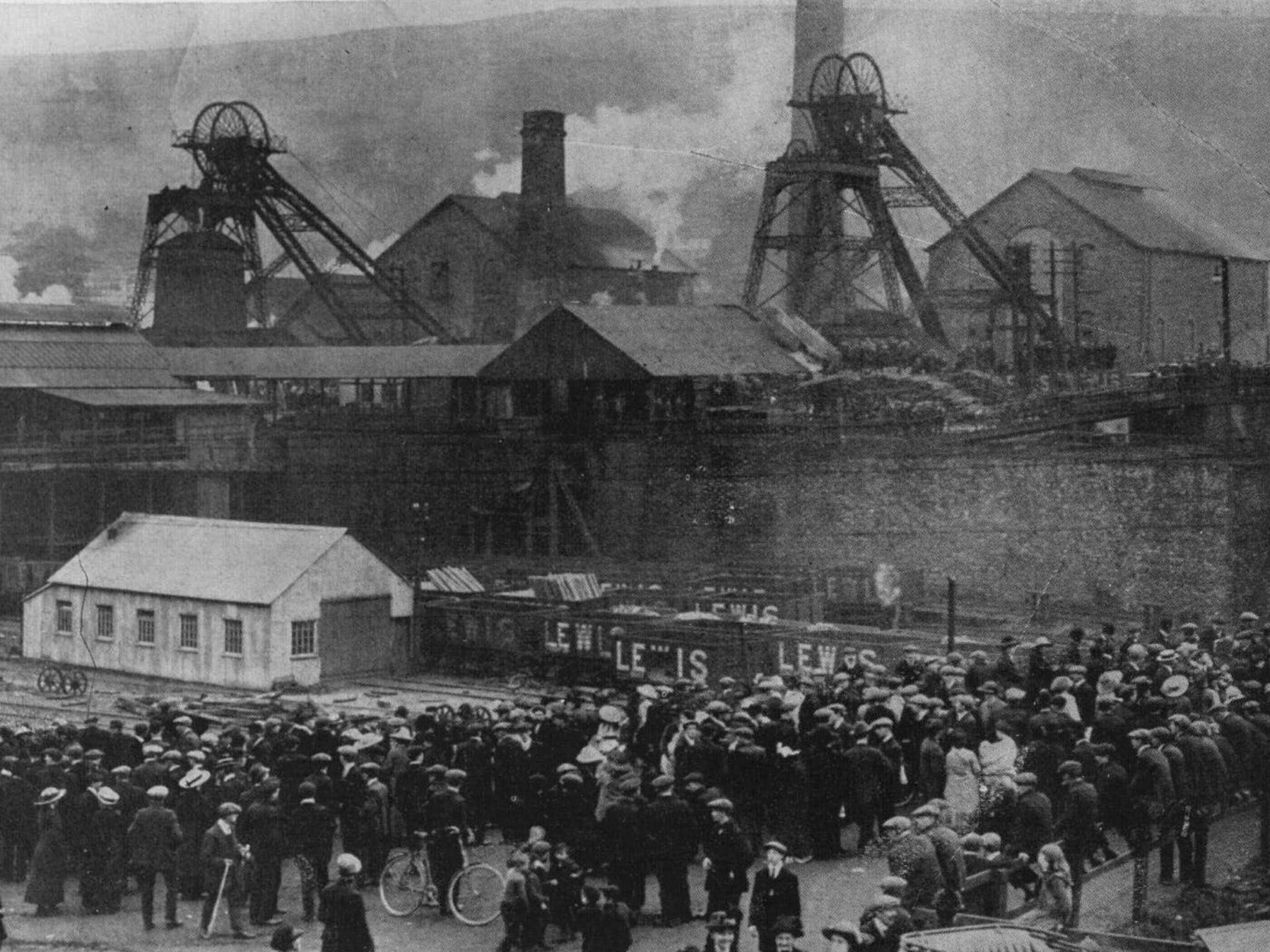

Your support makes all the difference.At 6pm on a Tuesday evening in Hopkinstown, two miles north of Pontypridd, news reached the surface that up to 70 survivors, men and boys, had been located below ground and were waiting at the foot of the mineshaft for cages, dispatched one by one, to raise them to safety.

Earlier that afternoon anxious wives and mothers had assembled at the pithead in the hope of glad tidings. And eventually these shocked colliers – exhausted, covered in soot, their hair bedraggled, their coarse clothing in tatters – emerged and stumbled home. A few were so weak they simply lay, almost lifeless, on the slats of a pony-trap.

***

From early in the 19th century, the coalfield of southern Wales grew to be the richest in the UK. At its peak, in 1913, it provided employment for a quarter of a million miners capable of extracting 57 million tons of the mineral annually – a fifth of Britain’s total. In that same year, the Port of Cardiff alone exported 11 million tons of top quality coal. Llanelli, Barry, Swansea and Newport were also home to huge coal-handling docks and marshalling yards.

Inland, towns like Merthyr Tydfil (population 7,700 in 1801; 50,000 just six decades later), Ebbw Vale, Tredegar, Rhymney, Aberdare and Pontypool – and of course, Pontypridd (which grew from a humble settlement population of 1,000 to 150,000 in 60 years prior to the outbreak of the First World War) – became synonymous with coal, iron and steel.

The first incident to take more than 100 lives occurred in Cymner in the Rhondda Valley in 1856: 114 dead. Two disasters followed a decade later in Ferndale, further upstream. The first, in 1867, claimed 178 lives, while two years later another tragedy resulted in 53 deaths.

The grim reaper returned to Rhondda next on 23 June 1894, when no fewer than 290 boys and men, together with 123 horses, were killed at the Albion colliery. Less than twenty years later, and just a little way away, the worst British mining disaster ever befell workers at Senghenydd, near Caerphilly. On that fateful day in the year before the start of the Great War, 439 miners and a rescuer all perished.

Explosions have been the cause of the majority of underground calamities. Sometimes, a single miner with a single stick of dynamite would bring bad luck on himself and a few standing nearby. On other occasions, massive blasts have ended the lives of dozens of breadwinners at the furthest ends of a tunnel, in seconds.

The silent build-up of carbon monoxide proved dangerous too. And on top of these dangers, hungry, ill-equipped and unprotected colliers had to contend with fatal roof-falls, flash floods, runaway coal wagons and faulty lift mechanisms.

***

For workers at the Great Western colliery in Hopkinstown, the date might have given a hint of foreboding.

After all, it was 11 April in 1877 when 14 miners at the Tynewydd mine in Porth found themselves trapped by floods. With water flowing in fast from a neighbouring, abandoned pit, the men’s only hope of survival was to keep their heads above the current.

The ensuing, heroic rescue effort occupied a full nine days, with all kinds of debate, frustration, setback, and change of strategy along the way. In our present age of rolling news, reporters from all over the world would no doubt have assembled at Tynwydd to follow events minute-by-minute. As it was, the Porth of 141 years ago did witness disaster tourism, plus a plethora of sensational newspaper headlines.

There was also great rejoicing at the fact that most of the trapped men emerged to tell the tale. Five did not, however.

But if the date of the Tynewdd disaster was imprinted in the minds of miners across Wales, there was no particular reason for the people of Hopkinstown to anticipate that tragedy would strike again exactly sixteen years to the day.

It was a Yorkshireman, John Calvert, who opened Gyfeillion Colliery in the Year of the Great Exhibition, 1851. After a first sale of Gyfeillion in 1854, the Great Western Railway took a controlling interest, hence the mine’s poetic name ever since, although ownership reverted to Calvert for a time.

In 1878, after discovery of the Six feet “Hetty” coal seam, Calvert sold again, this time to a reconstituted Great Western Colliery Company Ltd. The mine was expanded in 1890 with the sinking of the Tymawr shaft and the recruitment of several hundred more men, many of whom were really boys.

With Clement Attlee’s nationalisation of the coal industry still half a century away, mine owners were rarely safety conscious. Profit was their overriding motive. Labour was plentiful, non-unionised; and crucially, that workforce was replaceable. Technology was basic.

So it came to pass that disaster struck on 11 April 1893 at the Great Western.

The cause was an engine fire at the junction of two tunnels, nearly two-thirds and one-third of a mile from their respective disembarkation points. Attending to that powerful engine – one propelled by compressed air – that day was a substitute mechanic, who was stationed there when the engine’s wooden brake engine overheated and threw sparks out that ignited surrounding brattice (the timber or rough cloth covering a partition, or lining crudely hewn subterranean passageways). Straight away, the engine’s staging burnt out.

An hour later, the majority of the 900-strong shift had exited the mine successfully. That left approximately 50 men aged between 14 and 61 totally trapped by flames, billowing smoke, and collapsing pit props; 70 or so others were at serious risk of being similarly cornered.

A handful of gallant heroes set out to attempt a rescue. One, James Titley, should have been standing, secure, on a 4ft-wide landing at the bottom of the Tynmawr lift. Instead, he became disorientated in the midst all the smoke and heat and lurched forward as if to leave the cage prematurely. His brother Jesse saw the danger and grabbed James’s clothing. However, James’s shorn body was loosed and promptly fell into the abyss. When his remains were eventually located, Titley’s injuries were horrific.

William M Jones, Great Western’s draughtsman, in the company of Morgan Thomas and the aptly named John Valliant, assistant surveyor, were inspecting the Five-foot seam when they heard about the demise of the first four men trying to escape a reported engine fire. The threesome frequently found themselves overwhelmed by smoke and total darkness, and although they could hear the cries of their trapped colleagues, eventually they had to beat a hasty retreat, slumping together on the floor of the Tymawr cage ascending. The Tymawr shaft was then declared out of bounds for other rescuers.

None of this deterred the trio, once they felt revived, from sending barrels of water down a different shaft in order to douse the wild flames spreading towards that band of 50 or more men seemingly entombed. In time, they sent down a long hosepipe, which promptly snapped.

The fifth hero was an intelligent district fireman called Thomas Rosser, aged only 23, who realised at an early stage in proceedings that smoke and noxious fumes endangered the lives of the 72 men who were working on the Four-foot seam.

So it was Rosser ran towards two doors on the left of his watch; doors which were there to direct the mine’s air supply forward, so preventing it from making a short cut back to the Seven-foot seam 500 yards away. His presence of mind in breaking open the doors resulted in the major portion of noxious smoke passing, in a mighty but harmless gush, upward to a higher chamber, well away from the threatened 72.

Rosser’s rescue mission was, however, only just beginning. Having re-routed the air supply, he needed to gather together the 72 and persuade them to follow him, through thick and thin, towards the Hetty shaft. But that meant negotiating not only the burnt-out engine but also up to half a mile of intense heat, dust clouds, prohibitive roof-falls and associated hazards.

Each time a new obstacle was met, Rosser indicated to all the other escapees where they might shelter while he worked out when and how they might next proceed.

The whole trek – the sort of miracle usually seen only in a Hollywood movie – took over three hours. Even then, these gasping, dehydrated, exhausted, and improbable survivors had to wait for a cage to descend the shaft to take them to safety. When at last they ascended they encountered a thousand eager well-wishers hungry for news that was bound for many to be the saddest of all.

The eventual death toll of 63 comprised 48 colliers, three hauliers, two riders, two doorboys, one oiler, one fireman, one inclineman, one lampman, one engineer, one labourer, one roadman and a bratticeman.

The coroner for Cardiff, assisted by the coroner for Aberdare and a jury, convened an Inquest into the Great Western Disaster at the New Inn, Pontypridd, just over a fortnight later. No one was held directly to blame for what had happened, least of all the Great Western’s general manager, HT Wales, coincidentally son of the late and lamented Thomas Wales, who held the post of Her Majesty’s Inspector of Mines in South Wales.

However, recommendations were made that the width and surface of the braking mechanism of all haulage engines should be improved; also that more firemen should be on duty in the vicinity of mining equipment likely to overheat.

Despite the tragedy, the Great Western colliery continued to expand. The Four-foot seam was enlarged, as were the Five-foot and Nine-foot seams. A new Lower Four-foot seam was added. Prior to the outbreak of the First World War, the mine’s new owners had 3,162 men on their books and underground.

***

Few if any observers in 1893 would have predicted a series of coal pit closures in the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s; nor, surely, could they have imagined a year-long, and ultimately humiliating, miners’ strike.

And had you told those working down the pit in 1893 that the last deep coal mine in Britain would close little more than a hundred years later, they would never have believed it. Close it did though, in Yorkshire in 2015.

And what became of Hopkinstown? Well, it experienced tragedy again, on 23 January 1911 when a passenger train carrying over 100 people collided with the back of a freight train – a coal train, no less – killing 11 passengers.

At the Great Western, the Hetty shaft was closed in 1926. Other old shafts closed too and although new ones were sunk, production declined and the last coal at the colliery was brought to the surface in 1983. The colliery which had given so many men their livelihoods, and which had taken lives too, was demolished not long afterwards.

Mining brought prosperity to the Rhondda without doubt; but it brought darkness to the valley too: truly a valley of the shadow of death.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments