Why the Victorian myth of portraying paedophiles as strangers still persists today

Most child sex abuse happens within families, but we still cling on to the Victorian idea of paedophiles as outsiders

The Victorians portrayed paedophiles as scary strangers and social outsiders. By portraying them in this way, it was possible to avoid the unthinkable reality that children could be abused in respectable middle-class homes.

This myth of the stranger paedophile is still persistent today. And even though the evidence shows that most child sexual abuse is perpetrated by close family members, the stranger myth continues to distract our attention from the most common type of abuse.

The way we understand child sexual abuse today has its roots in social and medical theories developed in the late-19th century. The stranger myth originated partly in these theories and also in sensational journalism and popular fiction. Because it was a taboo subject, it was impossible to represent child sexual abuse directly in cultural works like novels. It was even difficult to discuss it in textbooks or newspaper articles, and the focus was kept firmly on stranger perpetrators.

An important event that helped make the discussion of child sexual abuse public was the publication of a series of newspaper exposés of child prostitution in 1885 by the investigative journalist, WT Stead. With the sensational title, The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon, the reports described a booming London trade in providing young girls for violent sexual exploitation.

Another event that opened up the discussion was the creation in 1896 of the medical concept of paedophilia. It was publicised in a very successful textbook on deviant sexuality, which focused on violent sexual crimes committed by strangers and almost entirely overlooked the act of incest. These treatments of the issue helped keep the focus off domestic problems. They allowed child sexual abuse to be portrayed as a lower-class problem of public morality, associated with stereotypes of poverty, slums, substance abuse and poor hygiene.

Gothic conventions

In the realm of fiction, some writers got around the taboo by using the metaphors of gothic writing to sneak sexual content past the censor. In this way, child sexual abuse could be represented using the figure of the monster who preys on children.

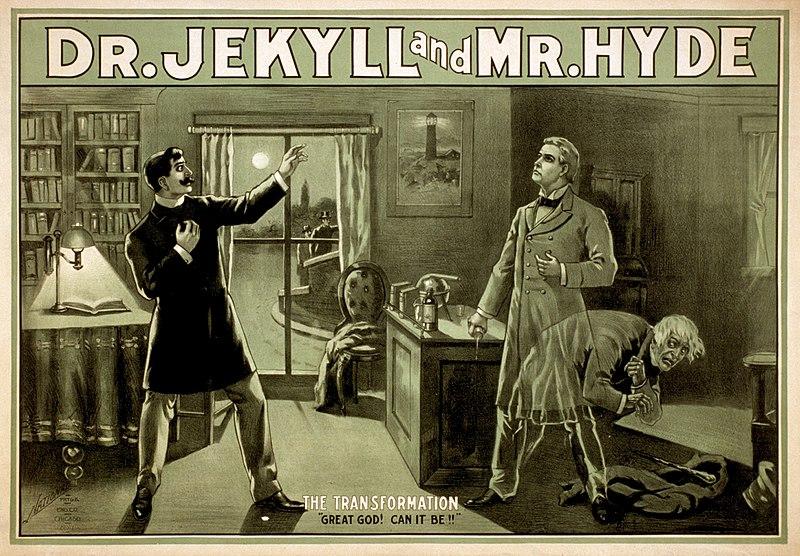

For example, in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), there is a bizarre incident where Mr Hyde cruelly tramples a little girl underfoot on a nighttime London street. This has been interpreted as a covert reference to the problem of child prostitution, coming just after the maiden tribute scandal the year before.

The vampirism in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, probably the best-known Victorian gothic tale, has long been interpreted as violently sexual. But the fact that most of the vampires’ victims in the book are children, means it too can be read as covertly representing child sexual abuse. By showing highly sexualised monsters preying on children, Dracula and many similar popular tales may have helped to circulate the stranger myth to a wide audience.

Gothic writing also gave credence to the stranger myth in another important way. Because it was difficult to describe child sexual abuse directly, even the non-fiction accounts often used gothic conventions to hint at unmentionable acts. The child prostitution articles used the sensational metaphor of the “sacrifice” of girls to the “insatiable” “maw” of “the London minotaur”. And the medical textbook, which featured a number of cases that involved cannibalism, even referred to the perpetrators of sexual murder as “modern vampires”.

Victorian attitudes die hard

Although it is no longer taboo to discuss child sexual abuse or to describe it explicitly, it is still not an experience or issue that is easily raised, especially when it occurs in a domestic setting. The focus is still on extreme cases committed by strangers and treated in a sensational way by the media, such as the disappearance of Madeleine McCann.

And the modern horror genre still seems to be used often to engage with child sexual abuse, with a continuing tendency to distance the perpetrators by making them monstrous. For example, in the classic 1984 horror movie, A Nightmare on Elm Street, Freddy Krueger was originally conceived of as a child molester, and this is made explicit in the 2010 remake.

Although we like to think we live in more enlightened times, we seem to be reproducing the unhelpful disavowal of domestic child sexual abuse that was so prevalent in Victorian times, and over-focusing on “stranger danger” and extreme cases. We are now willing to point the finger at institutional abuse, for example, but we are still unwilling to admit that child sexual abuse happens behind the closed doors of ordinary-seeming families. And this makes it even more difficult for the survivors of abuse to deal with their experiences.

Ailise Bulfin is a research fellow at Trinity College Dublin. This article was first published in 'The Conversation' (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks