How a mother’s search for the truth about America’s opioid crisis reached the White House

‘It’s clear my daughter died because of these drugs coming through our border,’ Susan Stevens said in Washington. But, as Eli Saslow discovers, nothing about the death of her daughter is clear

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.She’s spent the past 13 months retelling the story of her daughter to anyone who will listen, and now Susan Stevens, 53, speeds down the highway, needing to tell it again. Thirty people are gathered at a restaurant to hear a local sheriff discuss the opioid epidemic. Maybe, Susan thinks, she can talk to the sheriff about her daughter, Toria. Maybe this will be the time when the pieces fit together and the ending finally makes sense.

The car had belonged to Toria, and as Susan pulls into the restaurant’s car park, she can hear Toria’s lip gloss rattling around under the front seat. Her anti-overdose medication is still in the glove box, unused.

“It’s our special guest, straight from the White House!” says a hostess, greeting Susan at the restaurant, and it’s true. Two days earlier, Susan had been telling the story in the Rose Garden with Donald Trump. Before that was an anti-drug march. Before that was a middle school assembly. And before that was everything that had happened since the day she saw her 22-year-old daughter dead on the bedroom floor with her eyes open and blood on her face, and a police officer responding to the scene of another drug overdose in America asked Susan whether she might have something important to say about it.

“Will there be time tonight for questions and answers?” is what Susan says now, to the hostess. “I want to talk about Toria.”

“Yes,” the hostess says, leading her past the buffet to a back room of the restaurant. “I can’t believe you still have time and energy for a little thing like this.”

“I’ll go anywhere,” says Susan, who has talked about addiction to the paramedics who tried to revive Toria, to the drug dealers who sold her heroin, to the doctors who tried to help her, and to every elected official who has answered her phone calls. She collected and alphabetised hundreds of business cards in a binder, working her way up from county prosecutors to state senators to the US attorney general, until last month she was seated next to Trump in the Oval Office as they talked about how 90 per cent of drugs entering the United States come across the southern border. “We have new angel mums,” Trump announced, at a news conference minutes later, gesturing to Susan as he declared a national emergency to fund a wall along the US-Mexico border. “Stand up, just for a second, and show how beautiful your girl was,” he told her, and Susan held up a photograph of Toria as she listened to the clicking of camera shutters.

“It’s clear my daughter died because of these drugs coming through our border,” Susan said afterwards, to a bank of TV news cameras, and then she returned to North Carolina, where the more complicated truth was that nothing about Toria’s death seemed clear. Susan, a former private investigator, has been trained to work a case and then solve it, but this time, she keeps going back over the story, looking again for causes, reassigning blame and interrogating her own mistakes as she tries to make sense of one drug death in a national epidemic.

She listens to the sheriff’s presentation as he recites drug statistics she’s already memorised, and then she follows him to a corner of the room. “I just have to tell you that my daughter was a superstar,” she says, and before he can say anything, she begins describing Toria, her older child, the winner of middle school art contests, an aspiring chemist who had already been admitted to the University of North Carolina when she was caught during her final week of high school with one of Susan’s pain pills in her backpack. The high school called Susan, and instead of making up excuses for her daughter or pleading for lenience, she decided to let the school handle it.

“I thought I was doing the right thing, forcing her to learn a lesson,” Susan says, explaining that the school decided to call the police, who filed charges. Susan had gone to the courthouse with Toria to find a lawyer, who instead of helping Toria had assaulted her in his office. “That was the breaking point,” Susan says, her voice faltering as she describes the belt marks on her daughter’s back, the exam at the hospital, the night terrors and the pain pills Toria began carrying around in a gallon-sized Ziploc bag.

“Why did I let them call the police?” she asks, going back over the questions she’s spent the past year trying and failing to answer. “Why couldn’t I find a way to help her? I mean, what was I...”

“This isn’t on you,” the sheriff says. “These drugs don’t discriminate. The blame is on the drugs.”

She wipes her eyes with a napkin. “The blame is on the drugs,” she repeats.

She’s spent the past year mastering the talking points and learning the data behind a historic epidemic in the United States: 11 million people addicted to opioids. Drug overdoses killed more than 70,000 in 2017. The highest percentage of drug-related deaths in the world. In the 12 months preceding her daughter’s death, overdoses had killed more people in the United States than car crashes, guns or HIV ever had in one year, shortening overall life expectancy in the country by four months, the first regression since the Second World War.

And yet as difficult as it is for Susan to describe to officials the full scale of the problem, it is so much easier than returning to her house. Toria’s cats are on the couch. Her “Safety Crisis Plan” is on the entry table. Her last message is saved on voicemail. “I just... I really need to talk to you. I’m all alone right now. Please. Help me.”

Susan moved into the house with her two children a decade ago because she thought it might solve their family’s problems. She left her violent relationship in Florida for a rural area and enrolled Toria in a top-rated elementary school. Susan decorated the walls with annual school portraits, which have recently sent her searching back over Toria’s life, looking for the moment at which her problems began. What if Susan had moved from Florida earlier, before her daughter, then in kindergarten, witnessed the abuse and started clinging to her leg during the worst of it? What if the mistake was moving at all, uprooting her children to a state where they knew nobody and where Toria was sometimes bullied?

Or maybe the real cause came a few years later, after Susan’s car crash, which broke her back in two places and required a spinal fusion, forcing her into a permanent disability with chronic pain in her chest and neck. Doctors prescribed 90 pills of Percocet each month. Why hadn’t she known to lock them up?

She takes out her phone. She opens her binder of business cards. She dials a state lawmaker and waits through the rings. “I’m calling to talk about solutions,” she says, leaving a message.

Across the room, she can see the dent her 19-year-old son, Jorian, punched into the door when she told him about Toria’s fatal overdose.

On the wall is one of Toria’s last pieces of art, a self-portrait titled Love Yourself, and on the edges, she wrote: anxiety, panic attacks, ugly, sexually assaulted, low self esteem, stupid, scars.

Toria’s addiction came straight out of the abuse. They went hand in hand

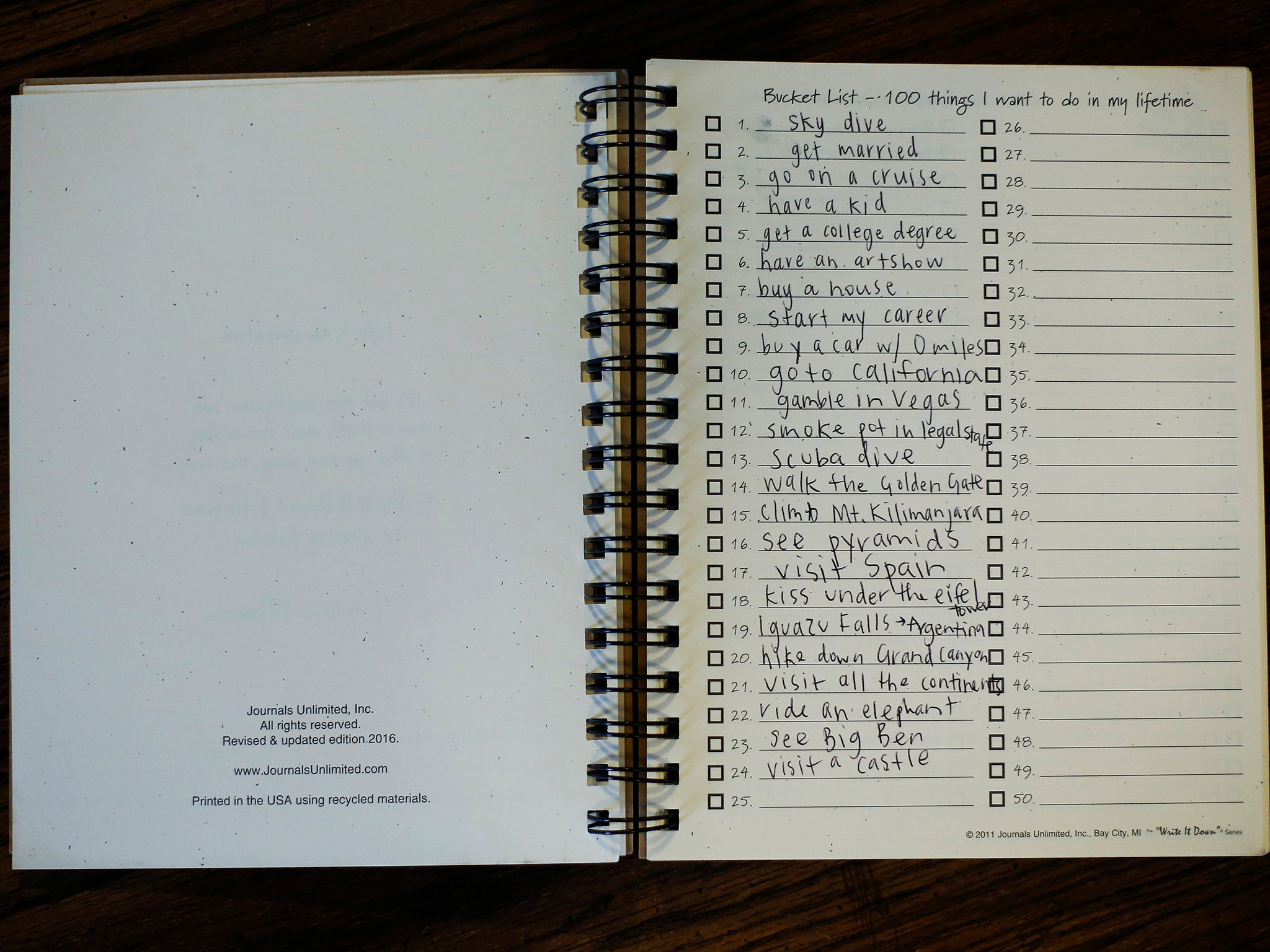

On the kitchen table is one of Toria’s journals, which Susan found a few weeks after her funeral, with a bucket list written on the first page: gamble in Vegas, have a kid, climb Kilimanjaro, kiss under the Eiffel Tower, have an art show, smoke pot in a legal state.

Susan grabs her keys. She’s been up since 3am, retelling the story even when nobody was awake to hear it, outlining chapters for a book comparing addiction to a hurricane and posting her daughter’s poetry on Facebook. Now she drives to a small office in downtown Winston-Salem. The space belongs to her friend Kenya Thornton, who runs a nonprofit to support victims of sexual abuse. Susan visited Thornton hours after Toria’s funeral to ask for help starting her own nonprofit to end opioid abuse, and within a few weeks, she incorporated, wrote 17 pages of bylaws, recruited a board of directors, created a website, and applied for permits to march on the National Mall in Washington. She named her organisation Tealdrops, after the official colour of recovery, and then she purchased a custom “tealdrps” number plate and bought a new wardrobe of teal dresses and jackets.

“Are you taking care of yourself?” Thornton asks, when Susan arrives at her office. “Did you get any rest last night?”

“I think so,” Susan says, and then she gets to the point of her visit. “We need to do more joint programming,” she says. “Toria’s addiction came straight out of the sexual abuse. They went hand in hand.”

“Addiction grows out of something,” Thornton says.

“For her, it was that brutal assault,” Susan says, but now she is also thinking about everything that led up to the assault: the medication she didn’t know to lock up; the pill Toria stole; the decision to let the school call the police; the day in 2014 when Susan first took Toria to see her lawyer, a 53-year-old public defender named Stanley Mitchell. They met in Mitchell’s office, and afterwards Toria said he looked at her in ways that made her uncomfortable. She told Susan she wanted a new lawyer – that she would pay for one herself – but Susan reassured her it would be fine. “There’s nothing wrong with him,” she remembers telling Toria, and a few weeks later, Toria was back at Mitchell’s office for a second meeting, which ended with her calling Susan from the car, screaming into the phone that she’d been attacked.

Susan met her at the hospital so doctors could examine her, and Mitchell was subsequently charged with two counts of forcible sex, assault on a female and sexual battery. He was disbarred for admitting to having sex with a client and convicted of assault as part of a plea deal in which the other charges were dismissed. Toria deferred her acceptance to university and began seeing a rotation of doctors, who diagnosed her with anxiety, panic attacks, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress and depression. She came home with prescriptions for Prozac, Xanax, Trazodone, Ambien, Hydrocodone and whatever else she could get.

“Why is your solution always another pill?” Susan wrote to one of Toria’s doctors, blaming him, but by then Toria was wearing long-sleeve shirts to hide needle marks and disappearing for long stretches into the bathroom, where Susan occasionally found her passed out.

“She had so much pain,” Susan says. “When I start digging into the reasons, it always goes deeper down and further back.”

“That’s why we focus on the things we can still do,” Thornton says.

“I know,” Susan says. “But maybe if I understand how it happened, I’ll be better at solving it.”

* * *

It’s the afternoon and Susan drives to Jimmy John’s (a sandwich chain) to see Toria’s former boyfriend Zach Ward. He and Toria were in an off-and-on relationship for the last five years of Toria’s life, and for some of that time, Zach lived in Susan’s house. She had referred to him as her future son-in-law. Now she steps up to the till and opens her arms. “Hey you,” she says.

He hugs her and then comes out from behind the counter to sit with her at a table in the empty restaurant. “How have you been?” she asks, and he says he is “adulting” – managing a Jimmy John’s, preparing to buy a house, settling into a new relationship that feels like it could last.

“So she’s really the one?” Susan asks, and Zach glances down at the table. “You deserve something good,” Susan says. “She would have wanted that.”

Zach met Toria during her senior year of high school, when she started working at Jimmy John’s. They dated for a year before the assault, and then he supported her through more than three years of addiction as she cycled between recovery and relapse. Once, she managed to go a year without using drugs, and Zach encouraged her to re-enrol in education. Then he left for a few days to attend managerial training for Jimmy John’s, and when he came back, she had relapsed.

“She fought it so hard,” Zach says. “I’ve never seen anybody try harder at anything.”

“She was so close,” Susan says. “Why couldn’t she pull out of it?”

“It was never a choice,” he says. “She was so ashamed. She would have chosen anything else.”

They watched her addiction accelerate after the relapse – three overdoses within a year, twice on life support, fears of suicide that brought Susan out of bed every night so she could look into her daughter’s room to make sure she was still breathing. In a desperate effort to change their routine, Susan drained her savings to book a family cruise because she was suffocating in the house and Toria had wanted to visit Mexico. Then, the day before they were supposed to leave, Toria went into the shower, put her leg up on the wall and begun twisting it and slamming her arms against it, injuring it so badly she was unable to walk. She told Susan she had done it on purpose so she wouldn’t have to spend a week offshore with no access to drugs. Eventually, Susan asked her to move out, and Toria moved in with Zach a few miles away.

He came home from work one afternoon to find her overdosed and managed to save her by administering Narcan, a nasal spray that can reverse the effects of an overdose. Then he returned home the next day, and she had overdosed again. He called 911, gave her Narcan and tried CPR even though her lips were blue. By the time Susan arrived 15 minutes later, her daughter was dead, but she told police she wanted to see her anyway. They led her back to the bedroom, where at first Susan saw the Lilly Pulitzer duvet Toria had bought with her pay from Jimmy John’s and the pillows she had embroidered with her initials. Then she glanced below the bed and saw Toria, naked on the hardwood floor under a thin sheet with a needle at her side. Susan kissed her forehead and said she loved her and was proud of her.

“I needed her to know I was going to talk about her,” she tells Zach now. “I was going to do something about it.”

I want to talk about this everywhere. That’s how I’m celebrating her

“I think she knew that,” Zach says.

“I wonder about so many things I could have done differently,” she says.

“I don’t think there was anything anybody could do,” he says. Customers are coming into the restaurant, and a line is beginning to form at the counter. He stands up, hugs her and puts on his gloves. “Go easy on yourself,” he says, but she is already up from the table and heading towards the door.

Outside the restaurant, she hands out business cards for her nonprofit. “My daughter was a superstar,” she tells people.

On the drive home, she writes to a member of the school board. “The cartels are running this stuff directly into North Carolina. What if we instituted an anti-drug pledge?” she asks.

She calls a pastor to ask about outreach to churches as she walks back into her house. “I want to talk about this everywhere. That’s how I’m celebrating my daughter,” she says, and then she hangs up and notices her son, Jorian, sitting in the living room.

“You know how much I hate it when you say that,” he says.

“Say what?” she asks.

“Celebrating,” he says, holding the word for a few extra beats on his tongue. “We don’t celebrate the Holocaust. We don’t celebrate 9/11.”

“But I’m just, I’m thinking that if we can save a life in her memory, that’s honouring...”

He holds up his hand. “I know,” he says. “I get it. I don’t want to argue about the whole thing, but it’s almost a slap in the face when you say that word.”

“I’m not going to apologise for honouring her,” Susan says. “She was amazing.”

“Yes, but there’s more to it than that,” he says. He’s seen the report card that shows she missed nearly 50 days of school during her senior year and somehow still pulled off straight As. He remembers the way, after the assault, she began yanking at her hair and skin. He remembers finding her overdosed once on the floor of her closet, and he remembers his own high school graduation, where she stumbled around and then nodded off at the table during dinner.

“She was so smart,” he tells his mother. “I was in awe of her. She had a huge heart. She was basically a genius, and then I watched her piss it all away.”

“She wasn’t trying to hurt us,” Susan says.

“I know, but I’m telling you how it felt,” he says.

He starts to tell Susan about another memory, his last one of Toria, a story he’s never told Susan before. Toria called asking for help in the winter of 2017, and he answered only because he had deleted her from his phone and didn’t recognise the incoming number. She was always needing things, and he didn’t want to enable her. This time, she said she hadn’t eaten in three days, and she begged him to buy her food. He told her to meet him at McDonald’s. Then, on the way, he bought a $25 gift card for food and another for gas.

He sat at a booth and waited for her to arrive, and then she was tapping on his shoulder, eerily skinny and wearing big sunglasses. She had scabs on her face and needle marks on her arms. He bought her a meal, and she asked him to sit with her while she ate. He stayed for as long as he could manage it, about 15 minutes. Then he gave her the two gift cards and said he loved her, and she started to cry.

“What else did she say?” Susan asks, because this happened several weeks after the last time she saw Toria, on her 22nd birthday. Maybe there is a clue in it somewhere, a piece of the puzzle she has somehow missed.

“Nothing, really,” Jorian says.

“Yeah, but 15 minutes,” Susan says. “She must have said something, right?”

“I didn’t want to get into some deep conversation,” he says. “I didn’t want her to know about my life.”

“I never realised she was that hungry,” Susan says.

“I know a lot you don’t know,” Jorian says, and then he tells her about how Toria would sometimes brag to him in high school about experimenting with drugs. She’d shown him the marijuana scale she kept under her bed, and she told him about taking pain pills at school and how they made her feel “floaty”. Once, when the two of them were driving home during Toria’s senior year, she told him that she’d just tried heroin for the first time. He had screamed at her and called her an idiot, and she said she wouldn’t do it again.

Jorian knows his mother has traced the origins of Toria’s addiction back to the stolen pain pill and lawyer, but now he tells her: “The drugs started before.”

Susan looks at him.

“That made it way, way worse, but it started before,” he says.

“I wish you would have told me this back then,” Susan says, and as soon as she finishes the sentence, she regrets it.

“What the hell was I supposed to do?” he says. “I would have betrayed and lost my sister.”

“It’s just, maybe if you’d told me, I could have...” She stops herself. She takes a breath and reaches towards his arm. “It was stupid,” she says. “I never should have said anything.”

“She should have never gotten to that point,” he says. “Those were her steps. She laid that path.”

“I know. I’m sorry,” Susan says again, but now she is walking backwards down that path, reassigning blame, searching again for causes she might still be able to fix. Domestic violence. Bullying. Sexual assault. Prescription drugs. Heroin. The US-Mexico border. What more could she have done? What else can she still do?

She walks into the kitchen, flips open her binder of business cards, and starts dialling on her phone. She waits for an answer and then begins telling the story again. “My daughter was a superstar,” she says.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments